A series of infant deaths in the 1850s in New York raised serious questions as to what was causing it. Public health wasn’t a concern back then, and most people had no clue until an enterprising journalist busted the case wide open. Here, we’ll explore the infamous Swill Milk Epidemic and see how shades of it affect our modern life.

A Wave Of Infant Deaths

In the 1850s, New York was a bustling center of commerce and enterprise. It was also filled with people of all social classes. Yet, the lower and middle-class houses were having a huge problem. Some unknown source was poisoning their babies and they had no clue what it was.

Some estimates put the deaths at around 8,000 children per year. They would get diarrhea and shrivel to death because of a lack of water and nutrients in their tiny bodies. Medical diagnostics wasn’t a common practice during this time, so no one knew what was causing these deaths.

New York in the 1850s

When the city expanded rapidly in the early 19th century, New York faced a severe supply chain problem. Fresh produce and dairy that had previously been brought from rural farms couldn’t make it into the city promptly enough to serve the demand.

It was such a problem that, at one point, a bottle of milk was exorbitantly expensive. Of course, this was New York, a city of entrepreneurs. Surely, there would be a way to solve this problem and profit from the resulting solution, right?

Adapting For City Living

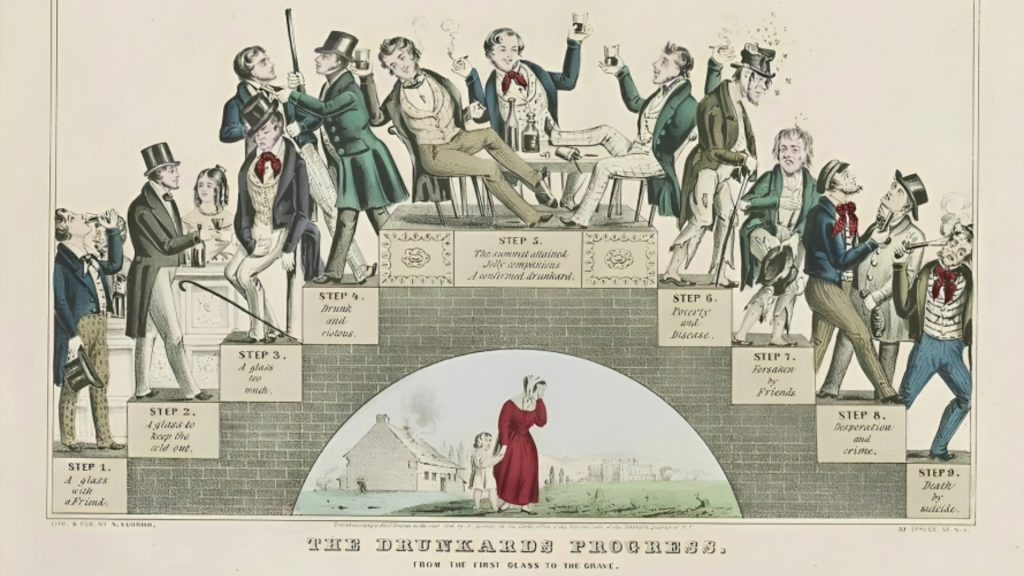

Dairy cows were brought into the city and housed in small, cramped quarters. Sometimes, they would be slung and held up to be milked easier. The poor creatures were then fed leftover mash from whiskey factories – another of New York’s producing businesses.

Because the cows were kept in such cramped quarters and fed such low-quality slop, the milk they produced would also be low-quality. The cows often got ulcers and died after a short while, but since the “dairy farming” operation was making money, it was easy to buy more cows.

Not Really a Fit Product for Public Consumption

Fans of history would recognize that no food and drug safety regulations were in force in the 1850s as yet. As a result, once you could produce milk, you could sell it. It was the most affordable milk on the market at six cents a quart, and low and middle-class moms swept it up to feed their kids.

It was of no concern that the original “milk” produced had a sickly blue tinge to it. Vendors realized many wouldn’t buy blue milk, so they mixed in additives like eggs, flour, chalk, and Plaster-of-Paris. This raised the milk’s color to align with what consumers would expect.

Moms Would Buy It Anyway

The lower classes of the city were always struggling to make ends meet. Having a new baby meant the mom would spend some time breastfeeding, but she would need to return to work as soon as possible to help provide for the family. Thus, weaning babies on milk early on was a necessity.

Social responsibilities fell on middle-class moms, and they, too, wanted to wean their kids off breast milk early. It would free them up to do all the social visiting necessary to maintain their social status. Many husbands were also eager for their wives to stop breastfeeding as a matter of etiquette.

No Options For Alternatives

Families in the low and middle-income brackets in New York were limited by what they could buy. Demand usually leads to increased supply, and some estimates state that between 50% and 80% of milk bought in northeastern cities was swill milk.

Fresh milk was available, but the prices were exorbitant. None of the parents of these families could afford milk at that price, but swill milk was much cheaper, readily accessible, and (at the time) considered healthy and safe to drink.

Early Warnings Were Ignored

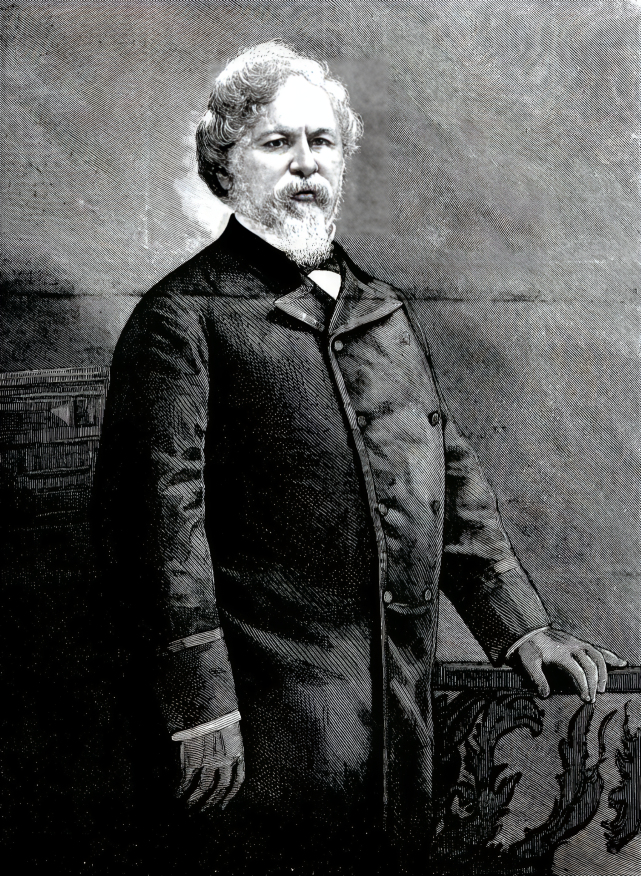

A temperance movement reformer, Robert Hartley, highlighted the problem with the swill milk (as it was then called) in the 1840s. However, his pleas for an investigation were brushed aside in New York, partially because of his politics.

As a temperance supporter, nobody in New York would give Hartley an ear because they didn’t respect the temperance movement. They figured that whatever Hartley had to say would be biased against distilleries, who were the primary producers of swill milk.

Deflection And Money Are Easy in The Big City

Another reason Hartley was roundly ignored was because he didn’t have any solid proof for his accusations. Germ theory was only just coming into popularity. Many of the distilleries used a combination of their money and influence to deflect the focus from their swill milk production.

Some distillery owners noted that no one could tell what was causing the kids to get sick. There was no such thing as public health systems back then that could trace the source of the problem, and so it was all about who could pay the most and speak the loudest.

A Champion Muckraker Rakes Some Muck

Sensationalism has always been a core part of the news, and Frank Leslie, a newspaper owner, decided to take up the cause against the swill milk producers. On delivery of milk to his newspaper’s offices, he found the product offensive and decided to look deeper into it.

In a dedicated campaign, Leslie took out full-page ads in opponent newspapers asking, “Are you aware what kind of milk you are drinking?” He published detailed maps and highlighted the poor working conditions of the farms.

Not A Saint, Either

Leslie came from a background of sensationalism, and he knew that images made the most impact. He had artists design pictures that would fuel outrage for what was being fed to kids and hopefully shed some light on the swill milk problem. But he wasn’t an angel either.

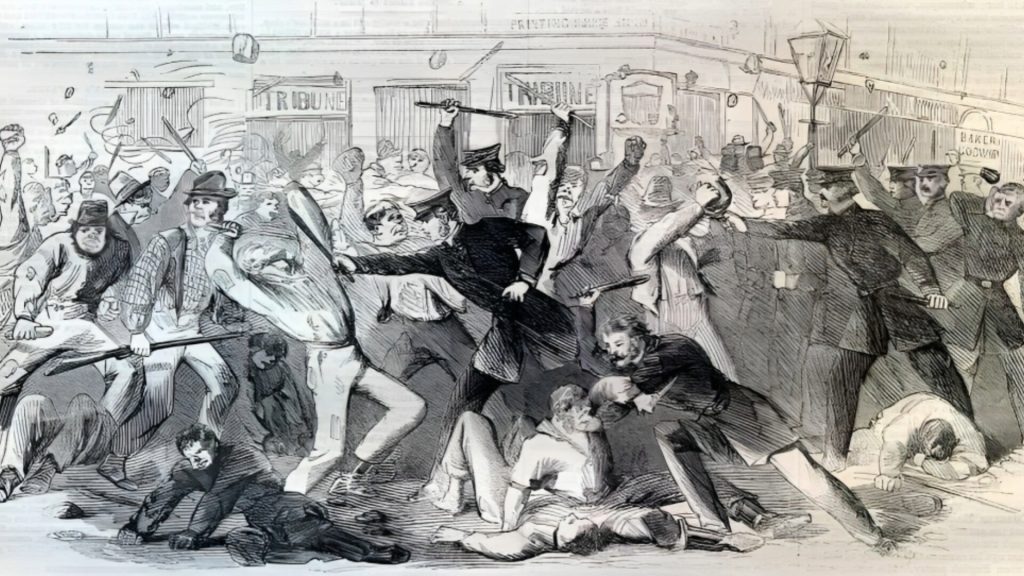

Part of his sensationalism relied on doing highly offensive caricatures of Irish dairy workers. It excited the existing anti-Irish sentiment in the New York commoners and even led to the “milkmaids” attacking some of his reporters and artists. However, he was successful in highlighting the swill milk problem.

New York in Uproar

The entire city came out in force once the news broke about swill milk. Angry mothers called for an investigation, with others lining up outside the doors of the dairies, waiting to attack anyone who went in or out. The City Council had to do something. So they did.

The Common Council sent out a group of aldermen to inspect the premises to ensure they were up to standard. Once again, we see how money and power come into play as the distilleries were warned well beforehand. They managed to clean up most of their act before inspectors arrived.

A Whole Lot of Nothing

After the inspections and inconclusive chemical tests on the milk, the aldermen all voted to keep swill milk on the market. It was somewhat unsurprising, seeing how much of the distilleries’ money was in their pockets. Their only suggestion was to make the cow pens more ventilated.

Leslie was, of course, livid. He published a cartoon showing the council members painting the cows white with a distiller slipping a bag of money into the councilors’ pockets. Leslie continued his activism, and eventually, it bore results.

Improvements Happened Little By Little

In 1862, New York issued milk regulations that addressed the deficiencies with swill milk. Even though it went a little towards improving the milk mothers had access to, it was woefully inadequate by modern standards. This wasn’t addressed until Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906.

Problems with milk additives that caused sickness also persisted. It was only until the early twentieth century when refrigerated train cars could quickly get fresh milk to the city, that the tides turned in milk consumption. This fresh milk was heartier and healthier for kids without making them sick.

A Lot To Unpack

Some authors use the Swill Milk Scandal to point out that natural foods are safer and more nutritious than manufactured foods. While there is evidence for this in some cases, the lesson we should take from this issue is different.

This debacle shows us how powerful interests can control legislation to ensure that they keep earning from others’ misfortune. It also highlights the importance of a working public health system to ensure that food and other consumables don’t lead to death on a colossal scale.

This Doesn’t Happen Anymore, Though, Right?

Since the Pure Food and Drug Act was passed, there have been fewer concerns about foods that actively poison people in the US. However, with new research coming out daily, an argument must be made for figuring out what is healthy and what isn’t.

In 2008, in China, milk and infant formula were cut with melamine, resulting in the deaths of thousands of infants. The lack of transparency in food production can still have untold effects on people today. The fact that we have safe, transparent milk production is all thanks to a muckraker with an axe to grind.