Female genital mutilation (FGM) has been outlawed in Gambia since 2015, but that could soon change if lawmakers decide to overturn the eight-year-old ban – something Gambian Parliament is currently debating, as we speak. If successful, Gambia would become the first country to reverse a ban on FGM – and Gambian activists are fearing the worst.

What Is Female Genital Mutilation?

Commonly referred to as female genital cutting, FGM is the process of cutting or removing all or some of the external female genitalia – also known as the vulva – for non-medical reasons. It is widely regarded as a violation of the human rights of girls and women.

According to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), more than 230 million girls and women alive today have undergone FGM – the strong majority of whom are from Africa (144 million), Asia (80 million), and the Middle East (six million).

Gambia Banned FGM In 2015

Between 2004 and 2015, more than 75% of all girls and women underwent FGM in Gambia – a small country in West Africa. That number has decreased dramatically over the past eight years, all thanks to former president Yahya Jammeh banning the procedure countrywide in 2015.

Still, many Gambian activists have criticized lawmakers for what they describe as a weak enforcement of that ban – with only two cases being prosecuted over the past eight years. Still, the ban was necessary then, and it’s even more necessary now.

New Vote Threatens To Repeal Ban

Last month, Gambian lawmaker Almameh Gibba introduced a bill that would repeal the 2015 ban on FGM – a move that has millions of girls and women across the country fearing the worst.

While that bill has yet to pass, lawmakers recently voted 42-4 in favor of sending the bill to a parliamentary committee for at least three months – giving them more time to debate before returning for a third reading.

Almameh Gibba Wants To Uphold Religious Loyalty

Almameh Gibba, a 41-year-old Independent Elected Member of Foni Kansala, believes a ban on FGM is a ban on a citizen’s right to practice their culture and religion. It’s important to note that Gibba is a male, and most people who support his bill are men.

“This bill seeks to lift the ban on female circumcision in the Gambia, a practice deeply rooted in the ethnic, traditional, cultural, and religious beliefs of the majority of the Gambian people,” Gibba said. “The bill seeks to uphold religious loyalty and safeguard cultural norms and values.”

Where Did FGM Originate?

Historians don’t know the exact origins of female genital mutilation, but there have been several findings throughout history that suggest the procedure isn’t a new concept – in fact, it has been around for thousands of years.

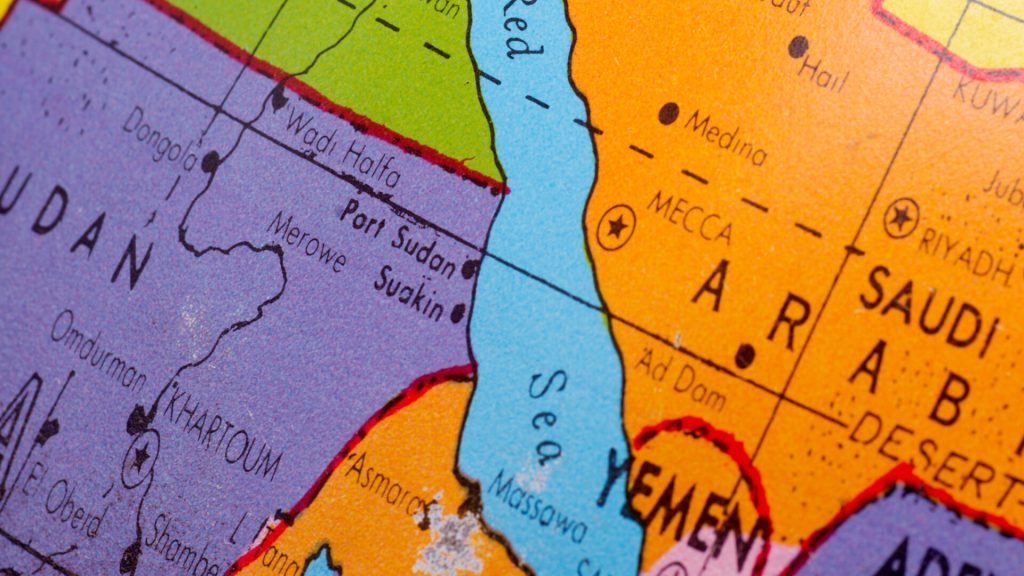

With that said, many experts believe FGM originated in Ancient Egypt and Ethiopia before spreading throughout Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. Today, FGM is most prevalent in Somalia, Guinea, Djibouti, Sierra Leone, Mali, Egypt, and Sudan.

5th Century BC: Earliest Origins Of FGM

While many people believe FGM was a product of Islamic or Christian belief, most research proves that the concept of FGM pre-dates both religions – with some historians claiming it originated in Ethiopa and Egypt in 5th century BC.

“Historians such as Herodotus claim that, in the fifth century BC, the Phoenicians, the Hittites and the Ethiopians practiced circumcision,” writes the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

163 BC: FGM Mentioned In Greek Papyrus

A Greek papyrus from 163 BCE detailed how girls of a marriageable age underwent ‘operations’ – though the exact nature of those operations are unclear. 140 years later, a Greek geographer documented that women were ‘circumcised’ during his trip to Egypt.

“It is also reported that circumcision rites were practiced in tropical zones of Africa, in the Philippines, by certain tribes in the Upper Amazon, by women of the Arunta tribe in Australia and by certain early Romans and Arabs,” the UNFPA added.

16th Century: Pietro Bembo And The Red Sea

Venetian historian Pietro Bembo was traveling along the slave trade route in the Red Sea when he documented the procedure being carried out on slaves – this was sometime between 1470 and 1547 AD.

“The private parts of the girls are sewn together immediately after their birth since an indubitable virginity at the marriage is held in such high esteem,” he wrote of his findings.

1609: João dos Santos Tells Of FGM In Somalia

Historians have also found a link between female genital cutting and slavery. An old letter written by Portuguese missionary João dos Santos shows the role FGM played in the slave trade route in Somalia.

“A group from Mogadishu (Somalia) has a custom to sew up their women, especially their slaves being young to make them unable to conception, which makes these slaves more valuable in the market both for their chastity, and for better confidence which their owner put in them,” he wrote.

2003: International Day of Zero Tolerance for FGM

Fast forward some 400 years and FGM is still being performed in more than 30 countries around the world. That’s why, in 2003, the United Nations introduced International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation as an international observation.

“Over the last three decades, the prevalence of FGM has declined globally. Today, a girl is one-third less likely to undergo FGM than 30 years ago,” the UN writes on their website – adding that they’re committed to ending FGM once and for all by 2030.

Why Do Countries Still Practice FGM?

There are several reasons why countries still practice FGM, but the most common include social acceptance, religion, hygiene, preserving a girl or woman’s virginity, making a woman ‘marriageable,’ and enhancing male sexual pleasure.

Doctors and researchers agree that there are no health benefits to FGM, but there are various health risks and complications that can occur – including serious bleeding, death, and childbirth complications. Most FGM procedures are carried out against the individual’s will.

Gambian Activists Believe This Is Just The Beginning

Those who support the ban are asking the same question – if they lift the ban, then what’s next? What other rights are they going to take from Gambian nationals? What is the end-all, be-all for those who have no regard for women’s rights?

“If they succeed with this repeal, we know that they might come after the child marriage law and even the domestic violence law. This is not about religion but the cycle of controlling women and their bodies,” said Jaha Dukureh, the founder of Safe Hands for Girls.