Oral stories hold significant historic value as they represent a unique and invaluable means of preserving and transmitting cultural, historical, and social knowledge from one generation to the next. But just how much credence should we put into oral stories? Without a written record, how can their information be authenticated?

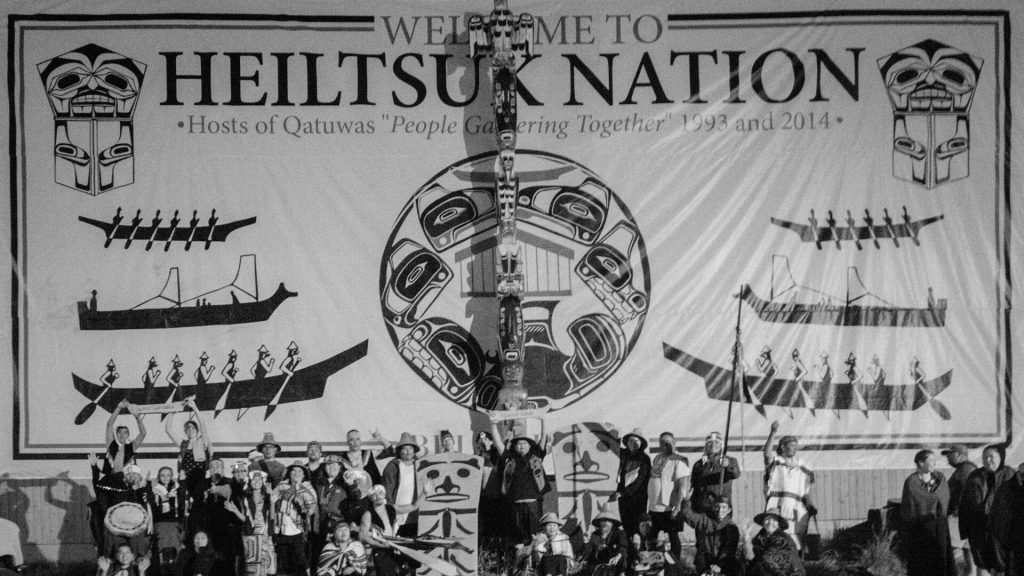

These were the questions that have long plagued the Heiltsuk Nation, an indigenous people from the coastal region of Canada’s British Columbia. The Heiltsuk people have continuously claimed land rights in the province based on oral traditions. Their claims have been disregarded because there is no evidence to support their stories. That is, until now.

Who Are the Heiltsuk People?

The Heiltsuk have inhabited their ancestral lands for thousands of years, residing in the central coast region of British Columbia. The Heiltsuk are known for their rich cultural heritage, deeply rooted in the coastal environment that has sustained them for millennia. Their traditional territory encompasses a vast and intricate coastal landscape, including islands, fjords, and forests.

The Heiltsuk people have historically relied on the abundant marine resources of the Pacific Ocean, engaging in fishing, hunting, and gathering to sustain their communities. The Heiltsuk Nation has a distinct language, Heiltsuk-Oowekyala, which belongs to the Wakashan language family. Their cultural practices, art, and ceremonies reflect a deep connection to the land and sea.

Oral Stories Versus Written Records

Before written language, many societies relied on oral traditions to convey their histories, customs, beliefs, and communal wisdom. Passed down through storytelling, proverbs, songs, and rituals, oral traditions serve as a dynamic repository of collective memory, reflecting the experiences and perspectives of diverse communities. But are they accurate?

Like the childhood game of “telephone,” information can change and evolve as it passes from one person to another. As each generation retells ancestral stories, tidbits of information may be lost or added to the tales. Over time, only a shred of truth may remain.

The Oral Stories of the Heiltsuk Nation

The Heiltsuk Nation, according to one of its members, William Housty, has a deeply rooted oral story that dates back to before the last ice age. As Housty explains, “Heiltsuk oral history talks of a strip of land … that never froze during the ice age, and it was a place where our ancestors flocked for survival.”

For this account to be true, the Heiltsuk people had to be in present-day British Columbia prior to the last time ice blanketed much of North America more than 20,000 years ago. Scholars dismissed this story as pure fiction. After all, it didn’t fit into the known timeline for North American habitation.

Human Habitation in North America

The most widely accepted theory to explain how humans populated the Western Hemisphere is based on genetic evidence. It suggests that a single group of modern humans crossed the Bering Land Bridge into North America about 16,500 years ago. From there, the theory states, humans spread across the continent.

For the Heiltsuk Nation to be in Canada ahead of the last ice age, humans would have had to cross the land bridge much earlier than scholars originally thought. It would mean the settlements the Heiltsuk people established in British Columbia were older than the Egyptian pyramids and the Roman Empire.

A Land Rights Claim

For many years, the Heiltsuk Nation exerted extensive land right claims in British Columbia, particularly in the Great Bear Rainforest, the world’s largest intact old-growth forest. However, these claims were brushed aside because the only “proof” was old stories that had been handed down over generations.

A recent archaeological discovery, however, backs up to ancient oral traditions of the First Nations people. As Housty noted, “Heiltsuk oral history talks of a strip of land in the area where the excavation took place.” What was discovered there is rewriting North American history.

Archaeological Excavations on Triquet Island

A team of archaeologists from the Hakai Institute, led by Alisha Gauvreau, conducted a dig on Triquet Island, located along the coast of British Columbia. Gauvreau and her team uncovered fish hooks, spears, carved wooden tools, and flakes of charcoal. Amazingly, these artifacts date back to before the last ice age.

The evidence was undeniable. Gauvreau and her colleagues found proof of an ancient village … the oldest known settlement in Canada and proof that the stories in the Heiltsuk Nation’s oral traditions are accurate. Housty said, “Now we don’t just have oral history, we have this archaeological information.”

Efficient Navigators and Hunters

The oral histories of the Heiltsuk Nation tell us that the herring was a staple of the group’s diet for thousands of years. A major part of the group’s culture centered on harvesting herring and on herring spawning times. There are also stories that show that herring was a commodity that the Heiltsuk people traded with others.

Gauvreau stated that the archaeological evidence supports the stories that the Heiltsuk Nation relied heavily on the ocean. “From our site, it is apparent that they were rather adept sea mammal hunters,” she said. The Heiltsuk people were accomplished sailors, and both hunted and fished from boats. It is entirely feasible, then, that they were able to cross the ocean by boats to settle in Canada.

Rewriting History

While the members of the Heiltsuk Nation rejoiced at the archaeological findings, scholars were forced to take another look at the accepted theory of how humans arrived in North America. But if they didn’t come to Canada via the Bering Land Bridge, how did modern humans travel to North America?

Gauvreau and her team think they know the answer to that question. “The alternative theory, which is supported by our data as well as evidence that has come from stone tools and other carbon dating, is that people were capable of traveling by boat,” she explained.