During the Cold War, there was a real fear among the American public that a trigger-happy Soviet official could launch nuclear missiles at the United States at any moment. Behind the scenes, the U.S. government and military were advancing their own Continuity of Operations plans.

Key to these plans were two so-called “doomsday” ships. These 1950s-era ships were upgraded by the U.S. Navy to serve as floating White Houses in the event of a nuclear attack on U.S. soil. Let’s take a closer look at these doomsday ships.

Heightened Concerns During the Cold War

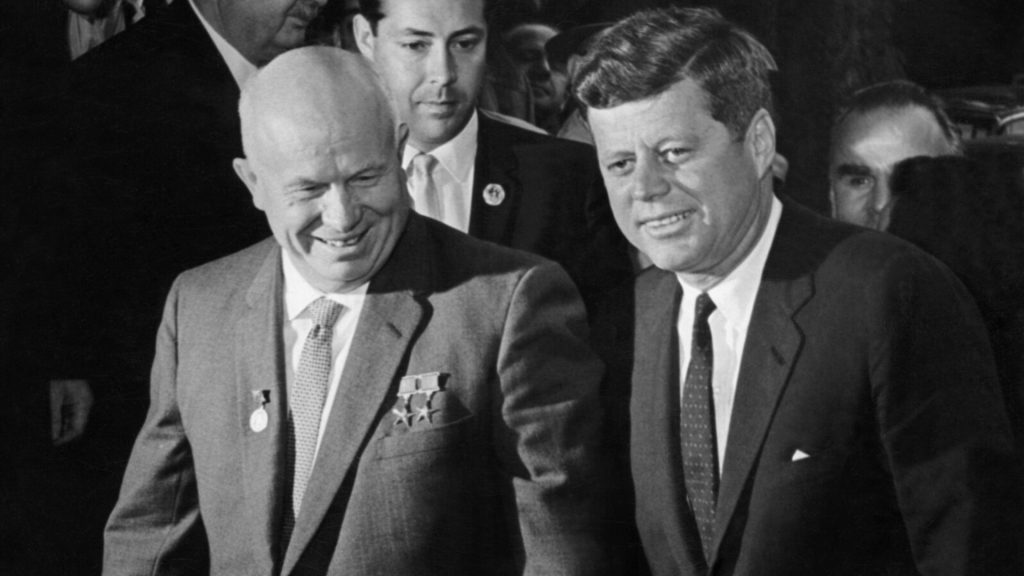

The period from the end of World War II to roughly the early 1990s is considered the Cold War era. During this time, the United States and the Soviet Union flexed their military muscles and trash talked at each other. Leaders on both sides feared that war could break out at any moment.

Adding to the worry was the fact that both the U.S. and the Soviet Union possessed nuclear weapons. There was a tangible fear of “mutually assured destruction.” While American citizens prepared their fallout shelters, the government prepared doomsday ships.

Continuity of Operations

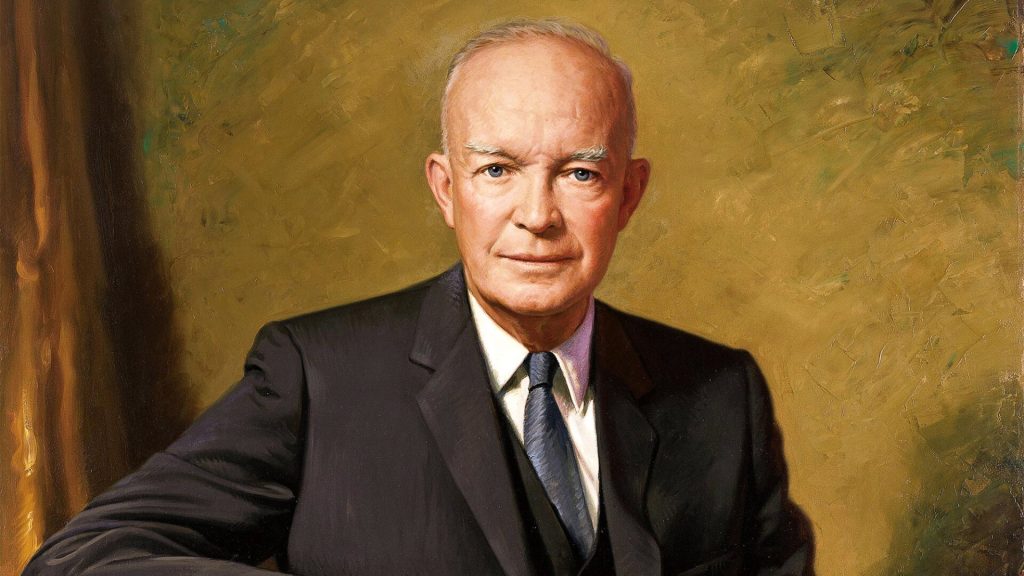

If the escalating tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union were to erupt into a nuclear war, the U.S. government had a plan in place. Actually, several plans. The Continuity of Operations plans were an executive order issued by President Dwight D. Eisenhower to ensure that the government could still function, even during a nuclear war.

These plans were multifaceted and included the construction of underground, nuclear-weapon-proof bunkers that could not only keep the POTUS safe but could also house all of Congress.

A Floating White House or Two

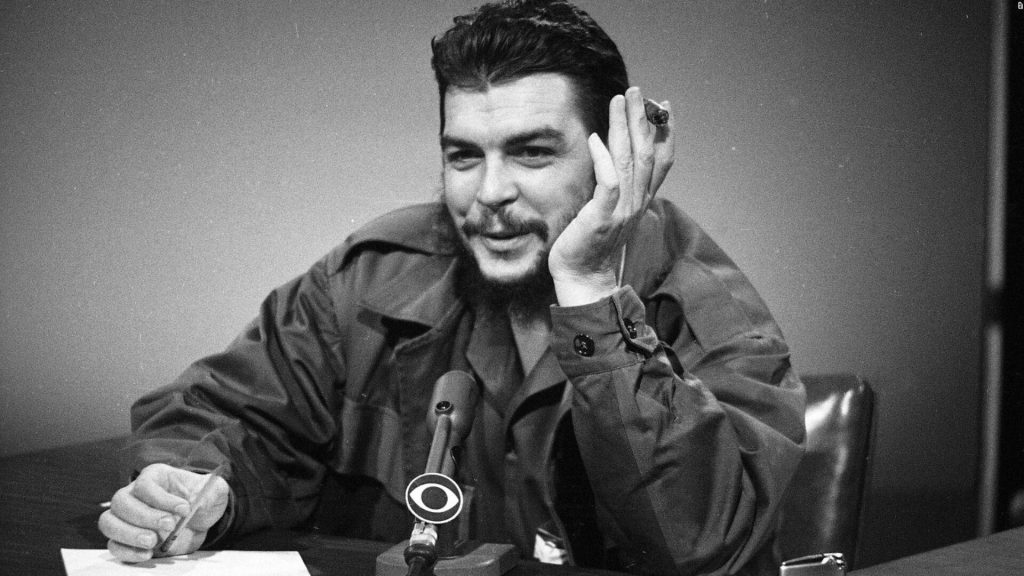

Emergency management experts understood that a mobile center of operations might be a better solution than a stationary one, like an underground facility. The United States, they thought, might be invaded by the Soviet army sneaking on shore from Cuba.

In that scenario, the U.S. government could operate from a secure place that could change location as needed. It was decided that not one, but two ships would be retrofitted to serve as floating White Houses, should the need arise.

Communication Was a Top Priority

It would be imperative for various parts of the government and military to be able to maintain secure communications with each other, therefore the Continuity of Operations plans called for establishing four command posts.

Those command posts would be the National Military Command Center, or NMCC; the Alternate National Military Command Center, or ANMCC, and the National Emergency Airborne Command Post, or NEACP. The last of these four posts was the NECPA, which stood for the National Emergency Command Post Afloat.

The USS Northampton and the USS Wright

In many ways, a floating White House is more vulnerable than the one at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. The decision was wisely made to have two ships readied to be floating command posts, in case one of them was disabled.

The two ships selected for this unique task were the USS Northampton and the USS Wright. As we will see next, the USS Northampton was built at the end of World War II but wasn’t completed in time to see action. The USS Wright, on the other hand, took part in dozens of assignments before being converted into a floating command station.

The USS Northampton, a Heavy Cruiser

Work began on the construction of the USS Northampton at the shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts in late 1944, but the work was halted in August 1945 as World War II drew to a close. But when plans for a floating doomsday ship were finalized, the Navy shook off the proverbial mothballs and got back to work on the Northampton.

Unlike the other ships in the Oregon City-class, the Northampton was built to be heavier and faster. Instead of nine guns in three turrets, the Northampton had twelve guns in six turrets. The ship was launched in January 1951.

Training Cruises and Diplomatic Visits

Fortunately, the USS Northampton was never called upon to become a floating White House. Instead, the crew of the ship used the vessel for ongoing training exercises. If a nuclear war broke out, the crew was ready to switch into Continuity of Operations mode and welcome the president on board.

During her time in service, the USS Northampton was occasionally used for NATO training exercises, public demonstrations, and to host tours for foreign dignitaries. King Olav V of Norway and King Baudouin of Belgium have both visited Northampton.

The USS Wright, a Light Aircraft Carrier

The Saipan-class light aircraft carrier, the USS Wright was commissioned into the Navy in February 1947. The United States military used the Wright to train pilots. They practiced landing and taking off from the deck of the aircraft carrier.

In this capacity, the USS Wright participated in 40 operational cruises, however they were not lengthy cruises. Most of them lasted only a couple of days.

The Wright Served Abroad

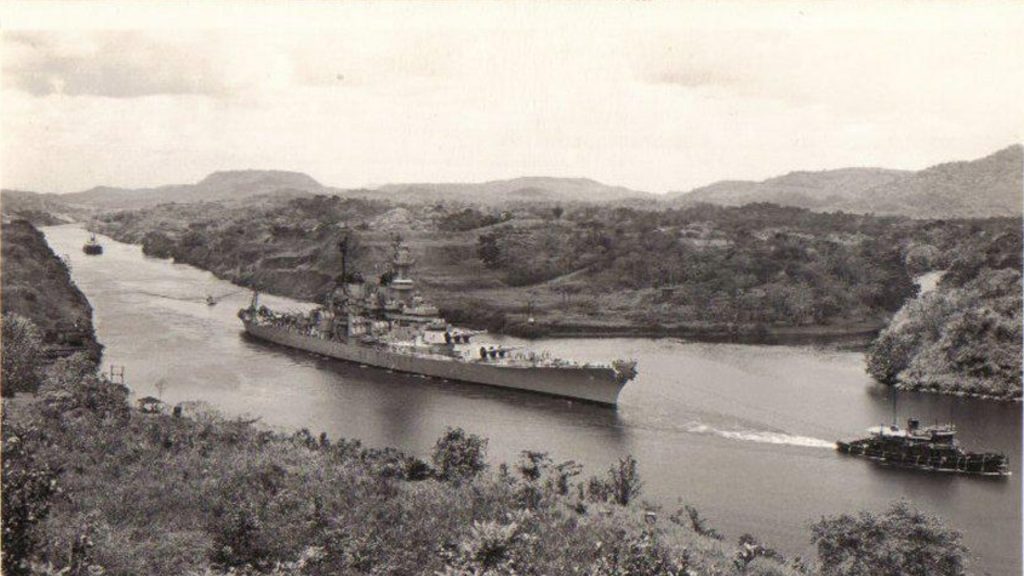

In 1951, the USS Wright was sent to the Mediterranean Sea to join the U.S. 6th Fleet. A few years later, the aircraft carrier sailed through the Panama Canal and stopped in both San Diego and Pearl Harbor before reaching Japan and Korea.

In 1962, the Wright was repurposed and redesigned to serve as a Continuity of Operations doomsday ship.

From Aircraft Carrier to Luxury Liner

As a doomsday ship, the USS Wright had “one of the most sophisticated communications platforms ever placed at sea.” One reason for this was because the landing deck was filled with various types of antennas. The landing deck may not have been able to accommodate a landing plane anymore, but the rear deck still had a functioning helicopter pad.

The ship’s hangar bays were converted into office and command space. One area, in fact, was remodeled into a posh presidential suite. Other areas underwent extreme renovations to turn it into a floating White House.

The USS Wright Saw Action as a Command Center

The USS Wright logged a few “command center” missions, but like the USS Northampton it was not needed to serve as a floating White House during a nuclear war. Instead, the Wright was used as a communications center.

In April 1967, President Johnson ordered the Wright to operate off the coast of Uruguay while he attended the Punta del Este conference, but its role was to allow the president to stay in contact with Washington. The Wright was put on high alert and readied for service in February 1969 during the Pueblo Crisis.

Did the United States Need a Third Doomsday Ship?

The United States government considered outfitting a third doomsday ship in the mid-1960s. The USS Triton was eyed for this job, as was another ship in the Saipan-class.

In the end, the U.S. Navy deemed it unnecessary to have three National Emergency Command Post Afloats, so this third conversion was scrapped. Both the Wright and the Northampton were decommissioned in the early 1970s.

Did That Mean the Threat Was Over?

The decommissioning of the two doomsday ships was not a sign that Cold War tensions were easing. The Cold War continued for another two decades, but both ships were becoming obsolete.

The president of the United States could, if it was deemed necessary, have a Naval ship at his disposal. But the world had progressed to the point in which the best doomsday ship was not a seagoing vessel. It was an airplane.

The National Emergency Airborne Command Post

In late 1974, the National Emergency Command Post Afloat was replaced by a National Emergency Airborne Command Post, a Boeing E-4. Boeing, bolstered by the success of its 747 airliners, produced four E-4 planes for the U.S. government.

One of the E-4s, E-4A, was outfitted and upgraded to serve as a flying doomsday facility. In the 1980s, the aircraft was upgraded with advanced satellite communication, nuclear and thermal effects shielding, and protection against electromagnetic interference. More E-4s were added to replace retired aircrafts. Two of them currently serve Air Force One and Two.