The Thanksgiving holiday is the fourth Thursday of November in America, and it is a time to come together with your relatives, both near and far. Many of us have been celebrating and learning about Thanksgiving as far back as elementary school, but how many of the facts that we learned as children are actually true?

Holidays Around Food are Centuries Old

American Thanksgiving is far from the first, or only holiday that centers around food. In fact, the practice of using food as a method of prayer or celebration goes back as far as the eleventh century, and has many different versions.

In various forms of Christianity, fasting or the practice of deliberately withholding food is meant as a response to an event that signals God’s judgment. These days were known as Days of Humiliation, and were meant to remind devoted worshippers of the power of the almighty.

Days of Thanks Were Meant to Celebrate God

On the other side of the coin, days of prayer and thanks were often ordered by royalty or high church officials in response to signs of God’s mercy. This could be as simple as a heavy rainfall that allowed a good harvest, or go so far as to celebrate the recovery from a group sickness.

Days of fasting and thanks were both celebrated by Puritan Christians for different reasons than their traditional Christian counterparts, and when a small faction of Separatists broke off to come to America, they brought some of their traditions with them. Among those traditions was rejecting holidays like Easter and Christmas outright, but days of thanks remained.

The Story of the First Thanksgiving

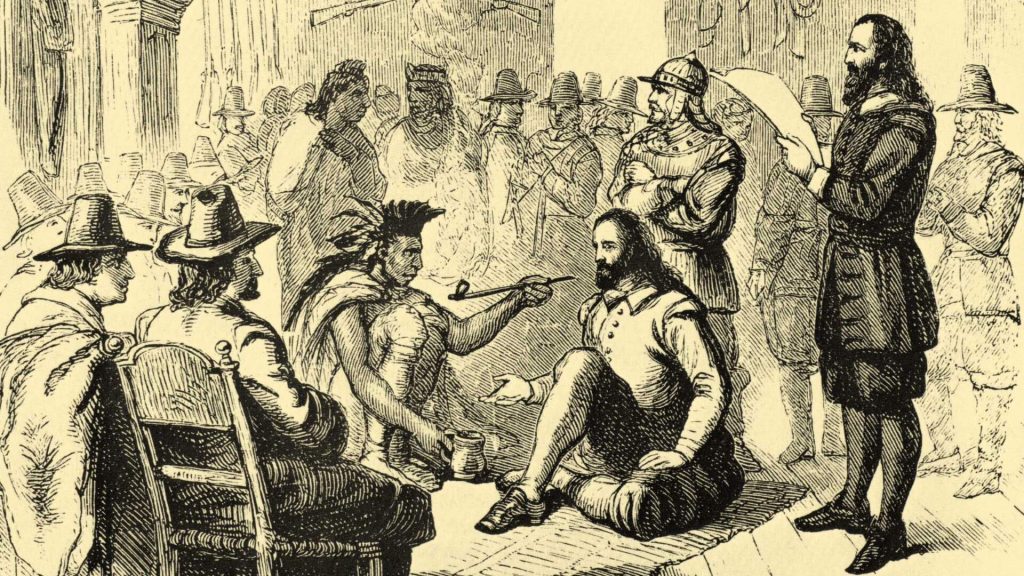

Many children in America learn about the tradition of Thanksgiving in relation to early Americans coming together with the American Indians for a day of celebration and harmony. The feast in question that is always referred to occurred in 1621, likely around the holiday of Michaelmas in September.

The history behind the feast goes back to an outbreak of disease that wiped out many Plymouth settlers as well as American Indians the winter before. The Wampanoag Indians sought an alliance with the better-armed English in their rivalry against another tribe, trusting that the English had not come to harm the native peoples.

The English Welcomed Help, and the Alliance

The English had also been hit hard by the disease the winter before. As such, they were more than happy to set up an alliance with the Wampanoag tribe after their leader helped provide provisions for the settlers during the harsh winter.

The feast took place over three days in September of 1621, and consisted of 50 Pilgrims and 90 Native Americans. The feast was cooked by four Pilgrim women, and while it was initially meant only for the English settlers, American Indians were welcomed warmly when they heard the celebratory gunfire and came to investigate.

Possibly the Second American Thanksgiving?

While the story that we learn of the first Thanksgiving is a heartwarming one, there is dissent among historians of whether that event was the first “true” thanksgiving. While the story of the Plymouth and Wampanoag feast takes place in Massachusetts, there are some historians who believe that the first American Thanksgiving feast actually took place in Florida.

In 1565, more than 50 years before the feast between the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims, a group of Spanish settlers landed on the shore in Florida and planted a cross to christen the settlement of St. Augustine. In order to celebrate their successful journey, the Spanish cooked and shared a feast with the local Timucuan people.

A More Traditional Thanks Practice…But Ultimately Not Important

The story of the Spanish in Florida more accurately reflects the more traditional practice of days of thanks. Days of thanks were rarely orchestrated on the same day every year, being oriented more around the events of the week or month or season that they were celebrated.

Even if the story of the settlers in Florida came first in the timeline of American settlement, the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag is the story that many know. It’s the story that much of our history is oriented around for the holiday, and whether it was the first or not is ultimately irrelevant in terms of modern culture.

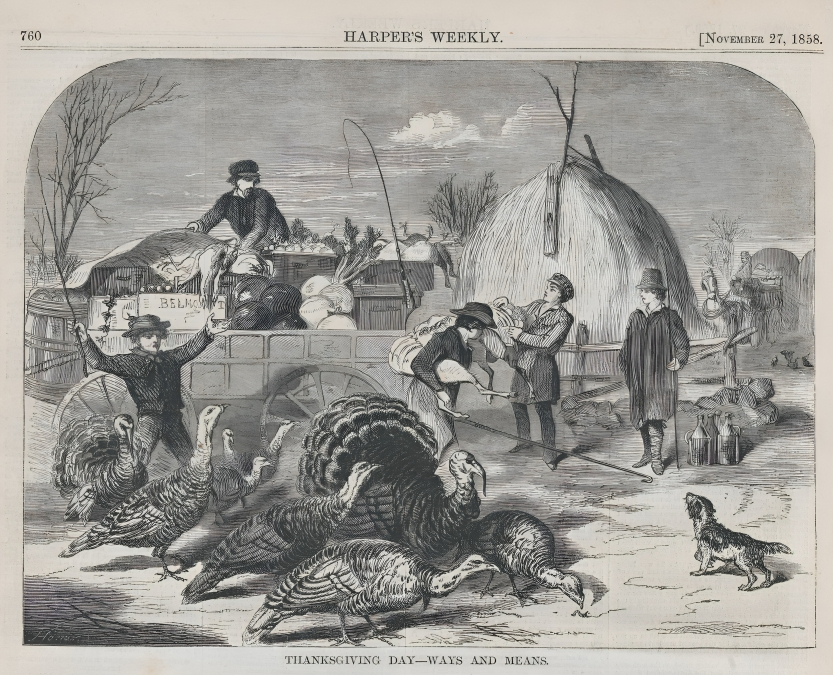

A Different Meal Than We Have Today

As far as what the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag tribe ate at that first Thanksgiving, many will not be surprised to hear that it likely looked very different than traditional Thanksgiving spreads. For instance, though the bird is indigenous to America, there was likely no turkey that graced the Pilgrim table.

Instead, accounts of the time report that the food on the table was largely local, and either brought by, or inspired by the Wampanoag tribe. There was likely deer and local seafood including mussels and eel, and a variation on a Wampanoag dish that consisted of boiled cornmeal and meat and vegetables. No potatoes, though!

A National Holiday was Called Much Later

As mentioned, days of thanks were largely local holidays that were meant to celebrate various good fortune by small groups of people. The first time that a national day of thanks was called for was after the victory over the British in the Battle of Saratoga.

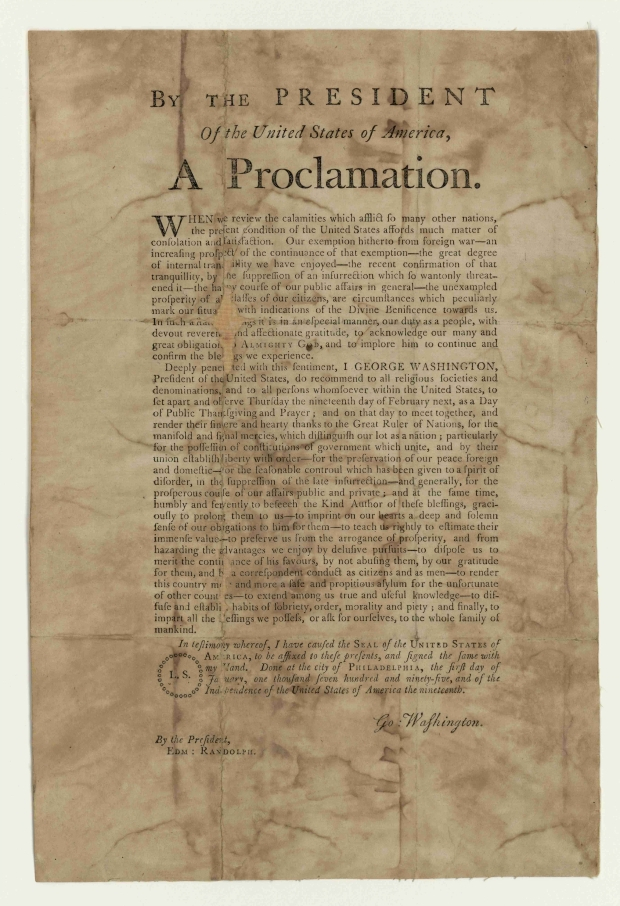

The second time was in 1789, when George Washington called for a celebration of the end of the Revolutionary War and the ratification of the Constitution. This day of thanks was called for on the fourth Thursday of November, which is the day that we continue to celebrate Thanksgiving on today.

Not Everyone Was a Fan

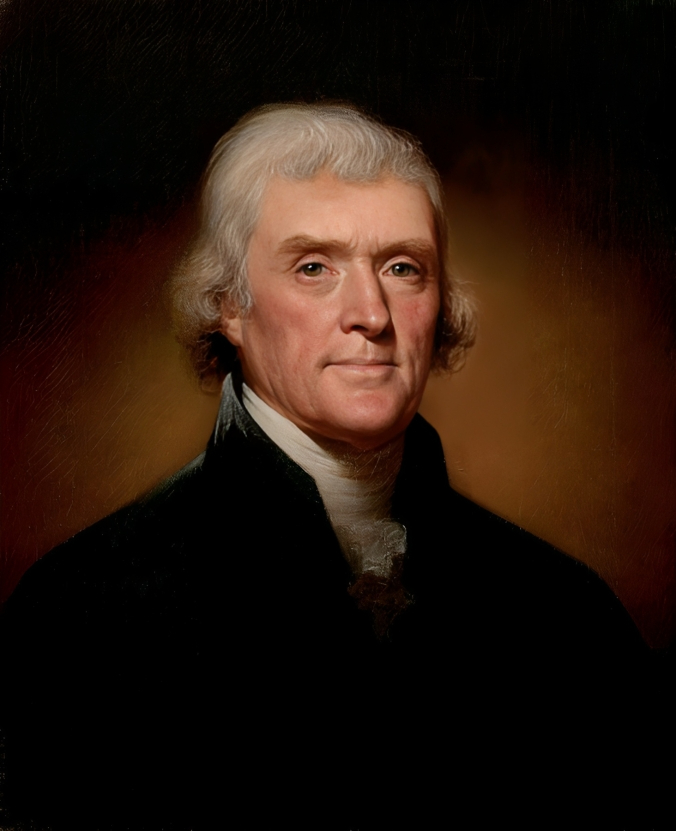

Despite the fact that George Washington called for one of the first nationwide Thanksgiving holidays, not every president was thrilled about the idea of a state-sanctioned day of thanks. Thomas Jefferson was famously the only Founding Father and president who refused to call for state-sanctioned days of thanks.

The reason for this was that Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States who ran under a Democratic-Republican platform, was staunchly against nationally ordained days of thanks. Unlike his opponents, the Federalists, he believed in a strict separation of church and state and thought that calling for a day of thanks would be akin to federally endorsing a faith.

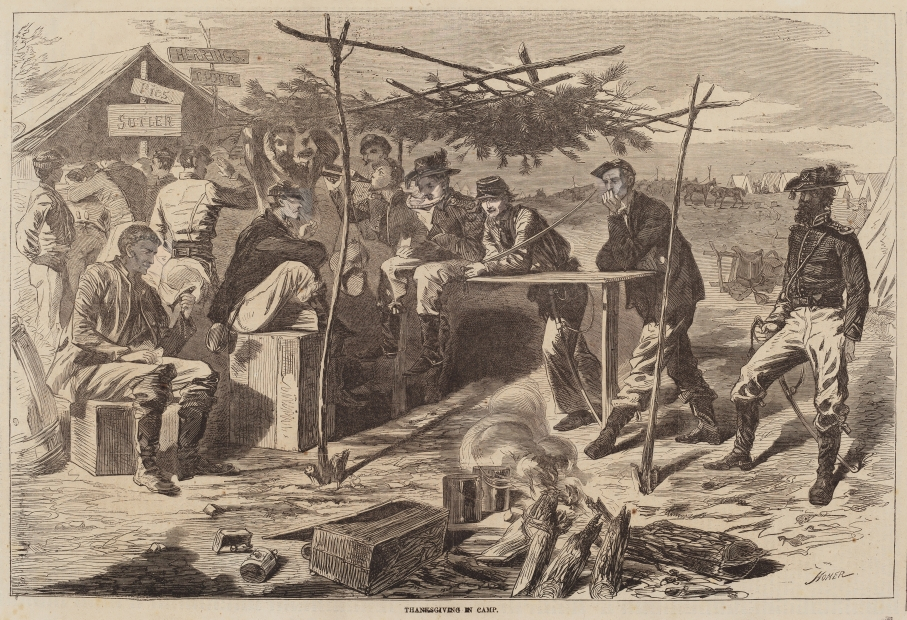

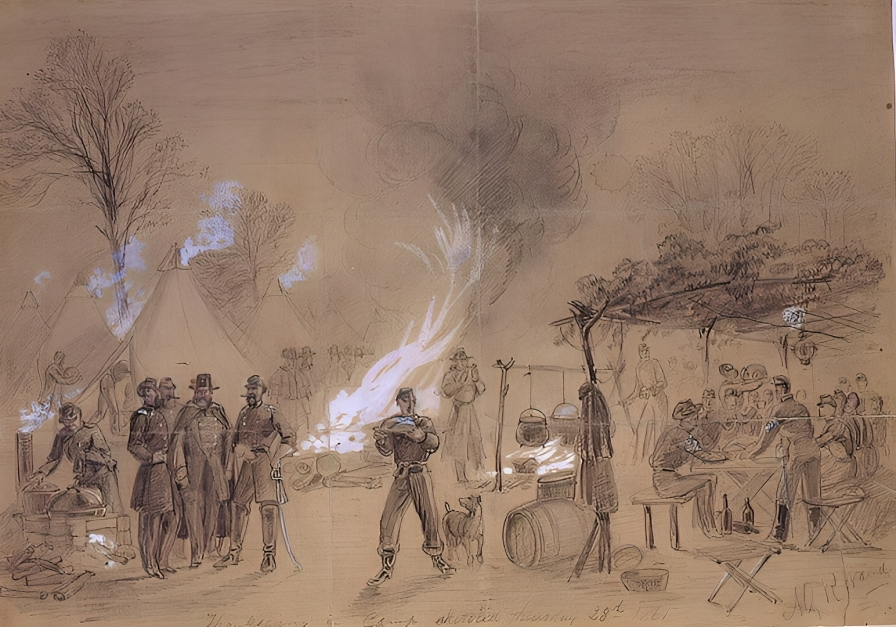

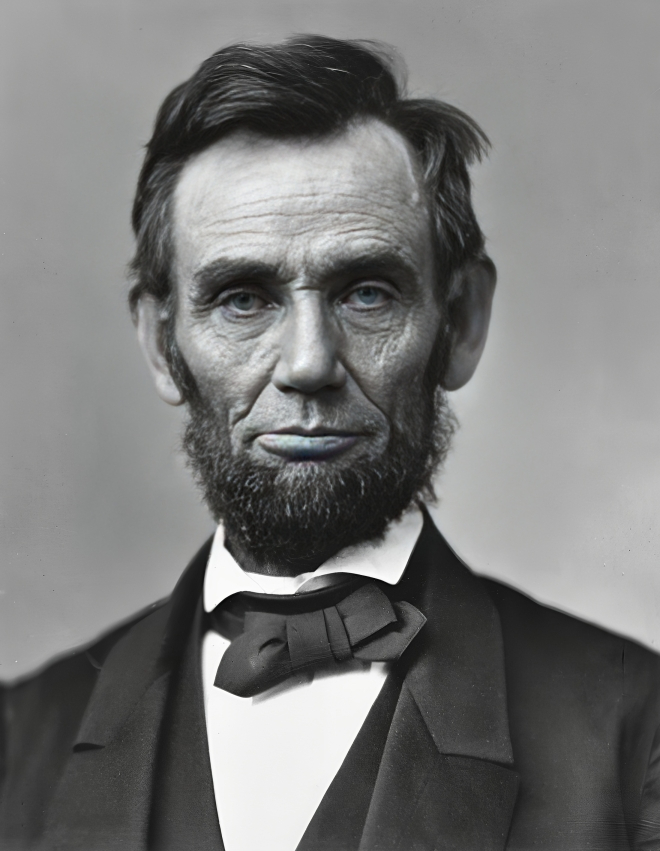

Thanksgiving Formally Declared by Lincoln

George Washington was the second to call for a national day of thanks holiday, it is true. But the first official proclamation of a national Thanksgiving holiday didn’t occur until 1863 under Abraham Lincoln’s presidency, who called for a national Thanksgiving Day to be celebrated on the final Thursday of November.

The story behind the proclamation is rather amusing. It had nothing to do with the Civil war or any of the current events that were happening at the time. Rather, it was in response to lobbying done by Sarah Josephina Hale, who was an American writer who authored the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”

A Formal Law, and Traditions Anew

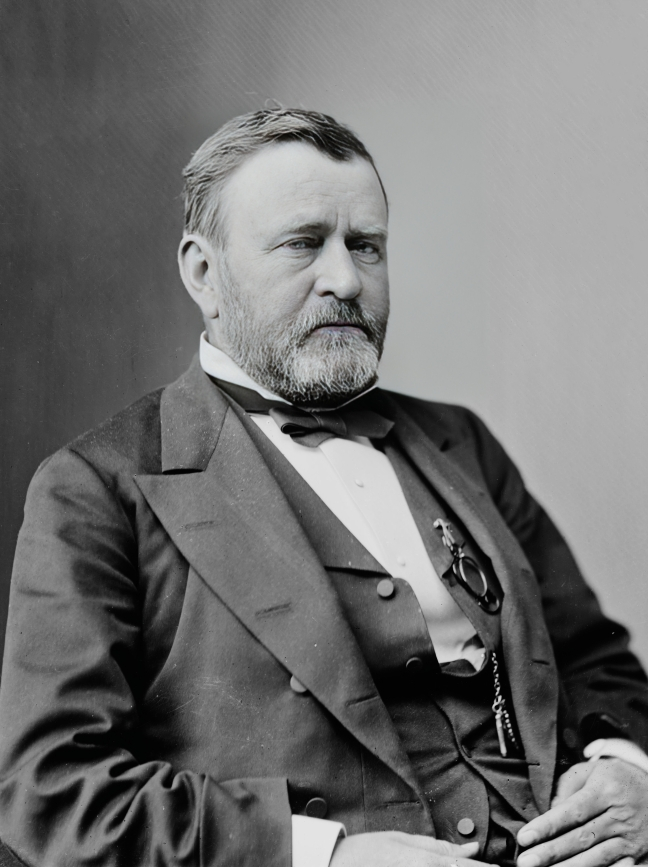

Thanksgiving Day was formally signed into law seven years after Lincoln’s proclamation, by President Ulysses S. Grant in the Holiday’s Act. This act also established three other holidays, including Christmas, New Years, and the Fourth of July. More holidays have been added since then, but 1870 was the true start of the national American Thanksgiving.

Other American traditions around the holiday sprung up shortly after that. The first Thanksgiving football game took place in 1876 between Princeton and Yale, and it was shortly afterwards that Thanksgiving was chosen as the date for college football championships. By the 1890’s, thousands of football games were played on the holiday every year, a tradition that has continued today.

The Drama Continued in the Twentieth Century

The back and forth over the legitimacy of Thanksgiving as a holiday in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was not the end of the drama around the holiday, though. In 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was concerned that the late holiday was cutting into the Christmas shopping season, and decreed that the holiday would be celebrated a week earlier.

Of course, there was uproar. Many Thanksgiving traditionalists refused to accept the change in date, and political rivals even went so far as to compare FDR to Hitler for the change. The decree was only accepted in 23 states, and in 1941 it was moved back to the fourth Thursday of November, where it has remained since.

Ultimately, a Day To Be Together, and Be Grateful

Thanksgiving is a wonderful time to be around family, be it family that you were born with or family that you make. The history of the holiday may be murky and fraught at times, but it doesn’t take away from the warmth and connection that the modern holiday brings.

Whether you stuff yourself with turkey or choose to stick only to sides, the holiday is one to make memories on. The shadowy history can’t take away from the message of connection and togetherness, and that’s what the holiday is truly all about.