When Spanish explorers and conquistadors arrived in what is now Mexico in the early 16th century, they claimed it was to establish Spanish colonies and spread Christianity to the native Aztec people of the area. But they had an ulterior motive for taking control of the region … gold.

The gold trinkets the Aztecs had led the Spanish to believe that there was a vast trove of precious gold in the New World and that the Aztec were hiding it. They learn of Cibola, seven cities made of gold, which they naturally wanted to see for themselves. But did Cibola even exist? Or was this a ploy to send the Spanish on a wild goose chase?

Cibola’s Roots Can Be Traced Back to Portugal

In the year 713, the Moors marched into Portugal and Spain and much of the Iberian Peninsula was controlled by Arab forces. In the city of Oporto in Portugal, the bishops packed up gold and other valuable objects to keep them from falling into enemy hands.

The priceless objects were loaded onto a boat and taken away from Portugal, never to be seen again. Centuries later, when Spain and Portugal arrived in the New World, they wondered if the lost Portuguese gold was hidden in the Americas. However, the more widely believed theory was that the New World was rich in natural resources, especially gold.

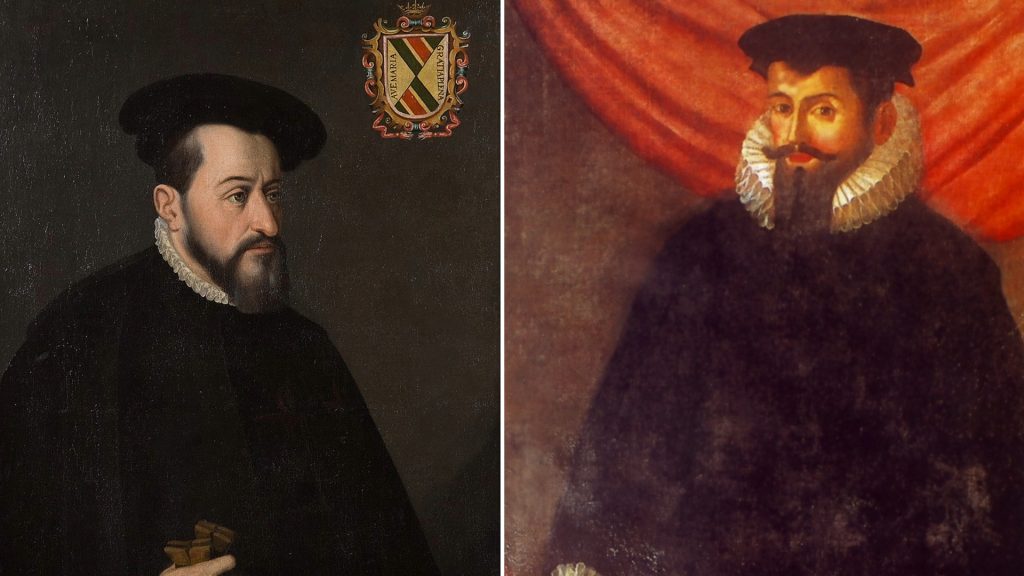

Cortez and Spain’s Lust for Gold

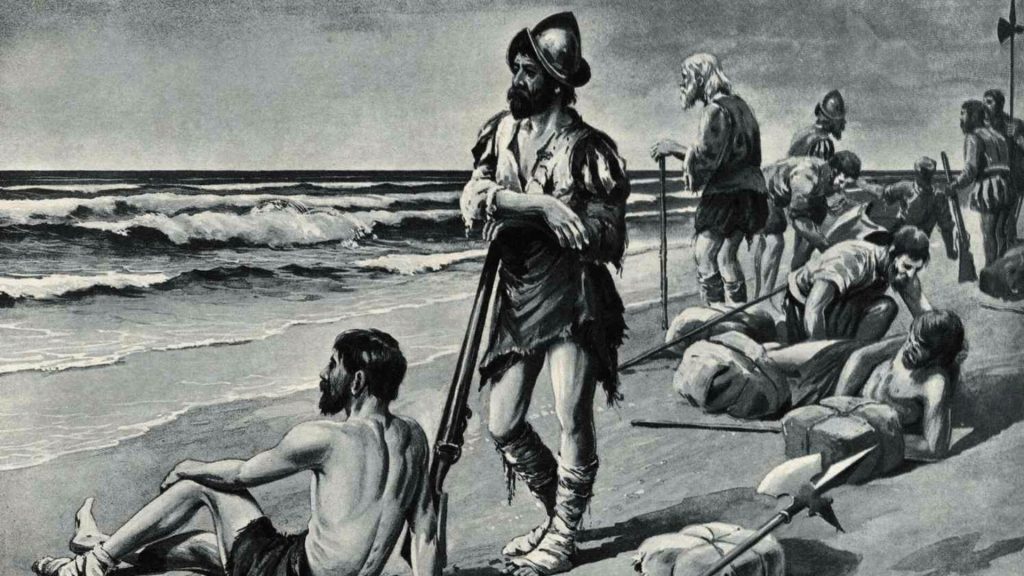

Spanish conquistador Hernan Cortez and his men landed in what is now Veracruz, Mexico, in February 1519. Under his leadership, the Spanish looted gold and other valuables from the Aztec cities to fulfill Spain’s lust for gold.

They found enough gold to make them think that there must be a vast cache of unimaginable riches in the New World. They demanded that the Aztec reveal the source of their gold. And the Spanish conquerors were convinced that the Aztec were holding out on them … that there was a hoard of gold they weren’t telling them about.

The Ill-Fated Narvaez Expedition

Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca led a 600-men expedition in 1527 on a trek around the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, including what is now Florida. Called the Narvaez Expedition, the group’s official mission was to scout the area for possible Spanish colonization. In reality, De Vaca was operating on orders to search for gold.

The Narvaez Expedition, however, was woefully ill-prepared for their mission. When their supplies ran out and they tried to raid indigenous settlements, De Vaca’s men were picked off by hostile natives. Eight years later, De Vaca and three of his men wandered into a Spanish fort in northern Mexico. They were the last survivors of the Narvaez Expedition.

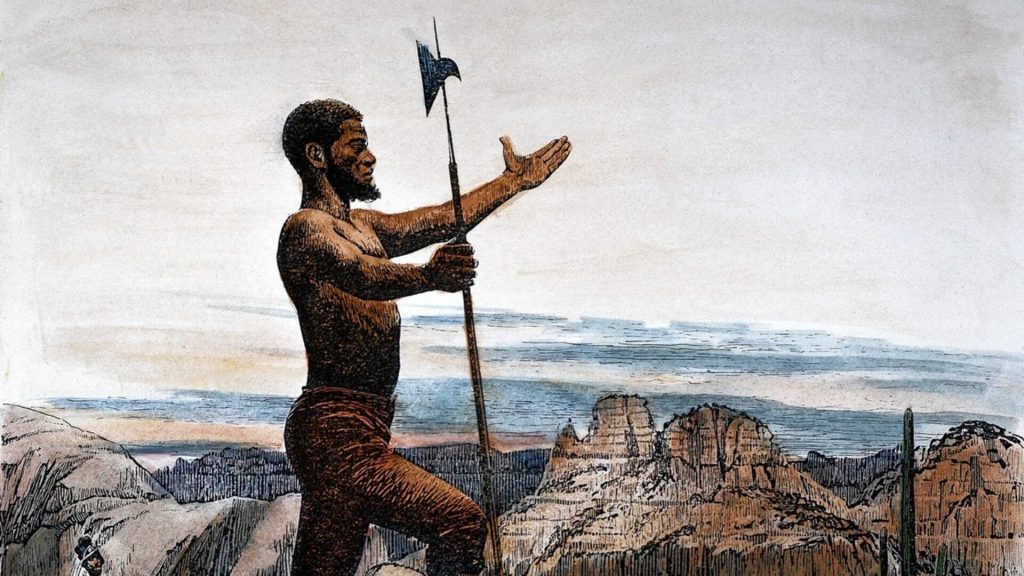

Esteban’s Incredible Tale

A slave named Esteban was one of the four men who survived the doomed Narvaez Expedition. Esteban was no ordinary slave. He was native of Azammour, Morocco, and listed as a “black Muslim.” He was well-educated and spoke several languages.

Among his duties as a member of the Narvaez Expedition was to go ahead of the main group to scout the area and make initial contact with village chiefs. According to the tale later told by Estaban, he was on a scouting mission when he saw the seven cities of gold.

Gold in the Streets

Estaban described the cities he saw as glimmering with gold. The buildings were several stories tall and shone golden in the sunlight. Goldsmith shops lined the streets. Even the roads themselves were made of gold.

The people, he claimed, were extraordinarily wealthy. They wore fine clothing with jewelry made of gold and precious jewels. Emeralds, turquoise, and other gemstones decorated the doors and windows of the buildings.

Estaban’s Second Expedition

Estaban’s unbelievable tale made its way to the ears of Antonio de Mendoza, who was the viceroy of New Spain, Spain’s name for what is now Mexico. Mendoza was eager to find the seven cities of gold that Estaban described.

Mendoza couldn’t go himself, so he recruited a missionary, Fray Marcos de Niza, to go instead. Niza, a Franciscan friar, questioned the native tribes he worked with about the fabled golden cities and was told that Cibola could be found “to the north.” In 1539, Niza, along with Esteban, led an expedition to search for Cibola.

The Cities of Gold in the American Southwest

Based on the vague information given to him by some of his recent converts to Christianity, Niza theorized that Cibola could be found somewhere in the area that now makes up New Mexico and Arizona. Esteban was killed by natives along the way, but Niza returned with a tale of wonder.

Fray Marcos de Niza claimed that he got within sight of the Cibola, but strangely, he said he didn’t actually go into any of the cities. Regardless, he described them in great detail. He spoke of streets of gold, tall, multilevel buildings, and incredible statues. All of it, he claimed, was made of gold.

Niza’s Second Expedition

Like Estaban before him, when Fray Marcos de Niza returned to tell his Cibola sighting, he was tapped to serve as a guide for the next expedition Spain sent to search for the Seven Cities of Gold. This expedition, also commissioned by Viceroy Mendoza, was led by Francisco Vasquez de Coronado and named after him. In addition to Coronado, Niza, a handful of priests, and 1,500 stock animals, the party included more than 300 Spanish soldiers and nearly 200 indigenous Mexican people.

Near present-day Gallup, New Mexico, the group found an amazing city with wide streets and houses that were several stories tall, but it was not made of gold. It was made of abode clay and home to the Zuni people. The Zini had a little bit of gold in their possession, but it was nowhere close to the fabled amounts of Cibola. Furious, Coronado attacked the village, ousted the Zunis, and set up his headquarters there.

Was Cibola in Kansas?

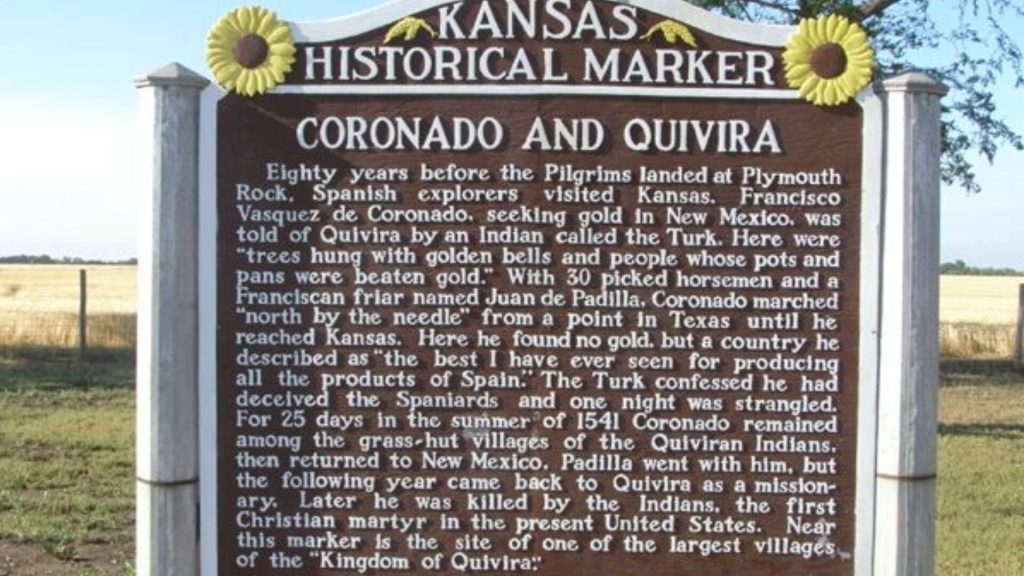

Coronado decided to fan out. He sent one of his captains to explore northeast Arizona and another to search the Grand Canyon. A third captain, Hernando de Alvarado, was sent toward Sante Fe, New Mexico. It was there that Alvarado encountered a man he called “The Turk.”

The Turk was a Plains Indian. When Alvarado explained that he was searching for cities of gold, the Turk told him about a land of riches called Quivira. With the Turk as his guide, Alvarado and his men set out for Quivira in April 1541. After about two months of traveling, they arrived in Quivira, a village near present-day Salina, Kansas.

No Cities of Gold Were Found

In Quivira, Alvarado and his men found a simple Native American village. There was no gold, nor was there a shining, sophisticated city. Alvarado confronted the Turk who finally confessed the truth. There were no cities of gold.

The Turk’s story was merely a ploy devised by the Zunis to get the Spanish to move on … to get them to look elsewhere for Cibola and leave them alone. For leading Alvarado and his men on a wild goose chase, the Turk was executed. But his confession raised an intriguing possibility.

Was Cibola a Wild Goose Chase All Along?

The Spanish conquistadors brought death and destruction with them to Mexico. The native Aztec people wanted nothing more than to placate the formidable invaders and to convince them to leave them in peace. The indigenous people quickly discovered what the Spanish really wanted – gold.

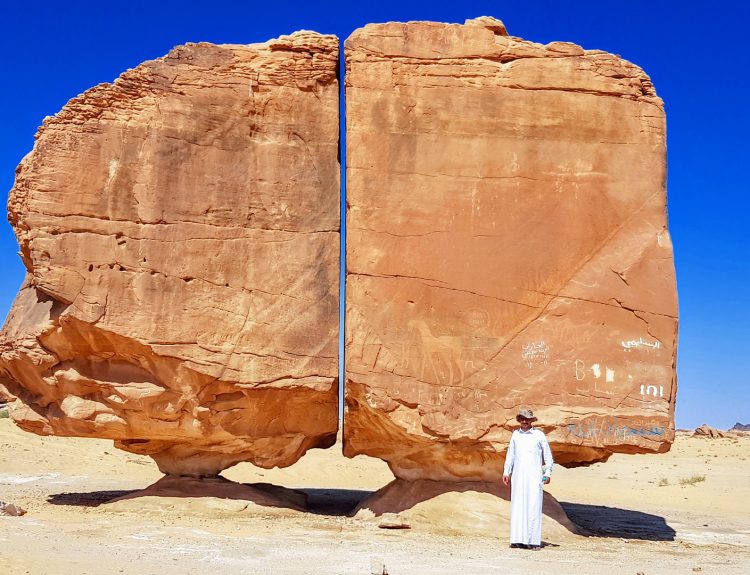

It is entirely possible that the stories of Cibola were either invented or greatly enhanced to get the Spanish to go somewhere else … to go “further north” to search for something they knew wasn’t there. Does that mean Estaban and Niza were also lying? Historians believe Niza’s story was fabricated, but Estaban may have mistaken the multilevel pueblo villages, made of orange-colored adobe bricks, for a golden city.