Forget the stereotypes that tell you Stone Age humans were nothing more than dumb cavemen (apologies to the Geico spokesman). The early humans living in prehistoric hunter-gatherer groups were skilled survivalists and, as evident in rock art in Namibia, keen observers and talented artists.

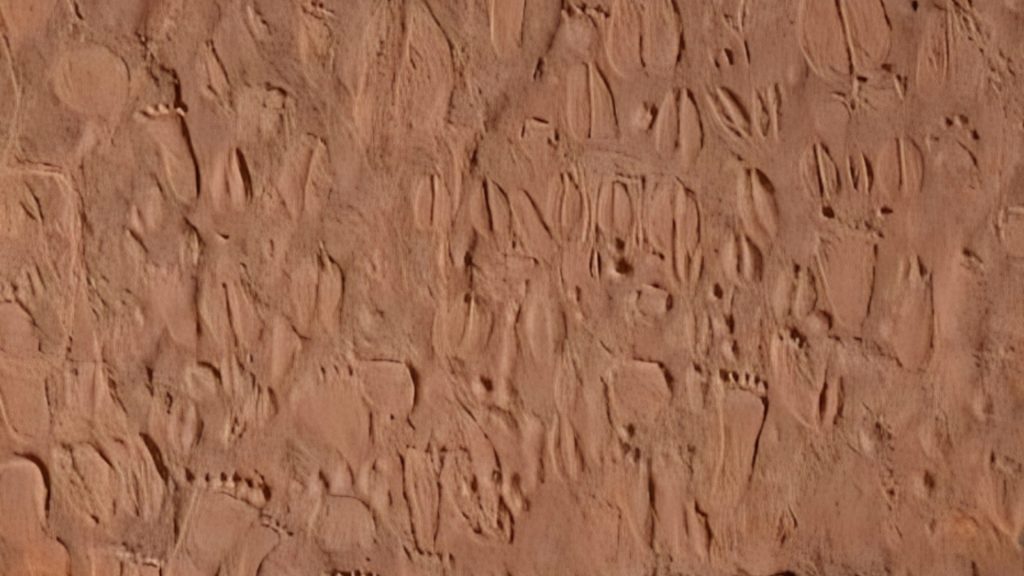

In Namibia’s Doro Nawas Mountains, there is a collection of engravings in the stone walls of caves that were carved an estimated 50,000 years ago. These engravings depict animal footprints that were so well-carved that it is possible to identify not only the animal, but the species and sex of it, too.

Where Are the Doro Nawas Mountains?

The Republic of Namibia is one of the world’s least inhabited countries, in part because it is the driest of all the sub-Saharan Africa nations. Namibia is located in southwestern Africa, bordering the Atlantic Ocean, South Africa, Zambia, Angola, and Botswana.

The Doro Nawas Mountains are located further inland from the Skeleton Coast. The rocky hills rise up from the dry plains. In fact, from the mountains, people have a panoramic view of the arid land surrounding the mountains.

Human Inhabitation in Namibia During the Stone Age

People have been home to early humans since prehistoric times. According to anthropologists, several groups inhabited the area thousands of years ago. The Khoi, San, Nama, and Damara people were prehistoric hunter-gatherers’ societies in the region during the Late Stone Age.

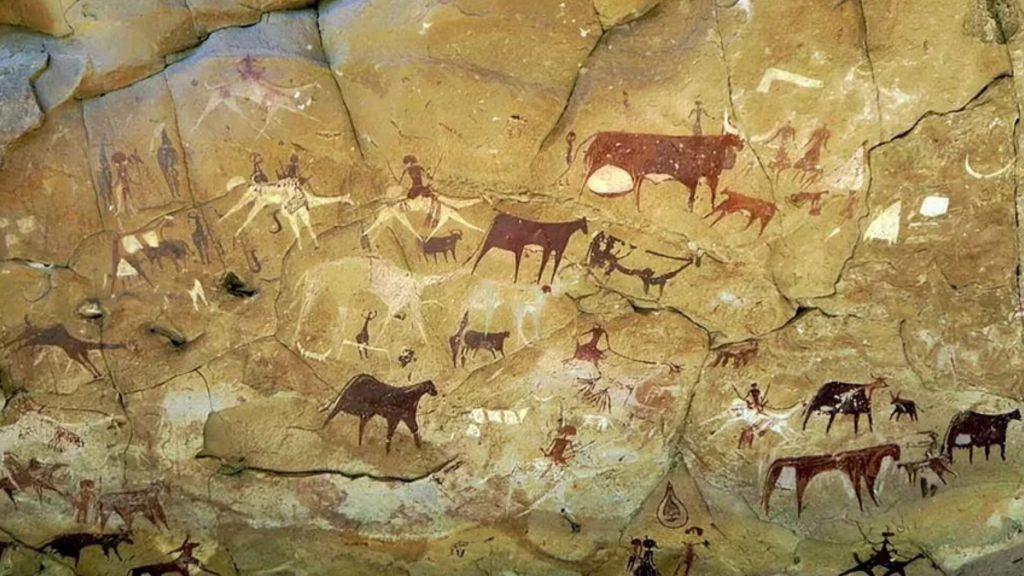

This period of human history is interesting because nomadic groups are beginning to form tight-knit societies. It is also significant because, as anthropologists point out, we see the emergence of art. These prehistoric people often left behind artwork – cave drawings and rock carvings – that provide clues to their lifestyles.

Prehistoric Rock Art and Cave Drawings

The desire and ability to create art is one of the evolutionary milestones of human development. Cave paintings and rock carvings from prehistoric times tell us that humans could think abstractly and creatively. It also is an indicator that they understood the passage of time and the need to record information for the future.

Plenty of artwork has been left behind by Stone Age people. Etchings, carvings, and drawings can be found in locations across Africa, Europe, and Asia, as well as in North and South America. The majority of the drawings depict animals and humans, possibly as a form of storytelling or to record hunting information.

The Carvings of Namibia’s Doro Nawas Mountains

The stone carvings found at Namibia’s Doro Nawas Mountains include a vast collection of animal footprints. As we will see momentarily, footprints – both human and animal – are a common motif in cave art. However, the carvings discovered in Namibia are exceptional in many ways.

The person or group of people who carved these animal footprints more than 50,000 years ago did so with such accuracy and attention to detail that, even today, it is possible to determine the species, sex, approximate age, and even which leg of the animal represented by each footprint.

Footprints in Time

As mentioned, the footprints of animals and humans are commonly found in Stone Age rock art around the world. But as German archaeologist Andreas Pastoors explained, “Tracks have not yet been assessed as a legible source of information.”

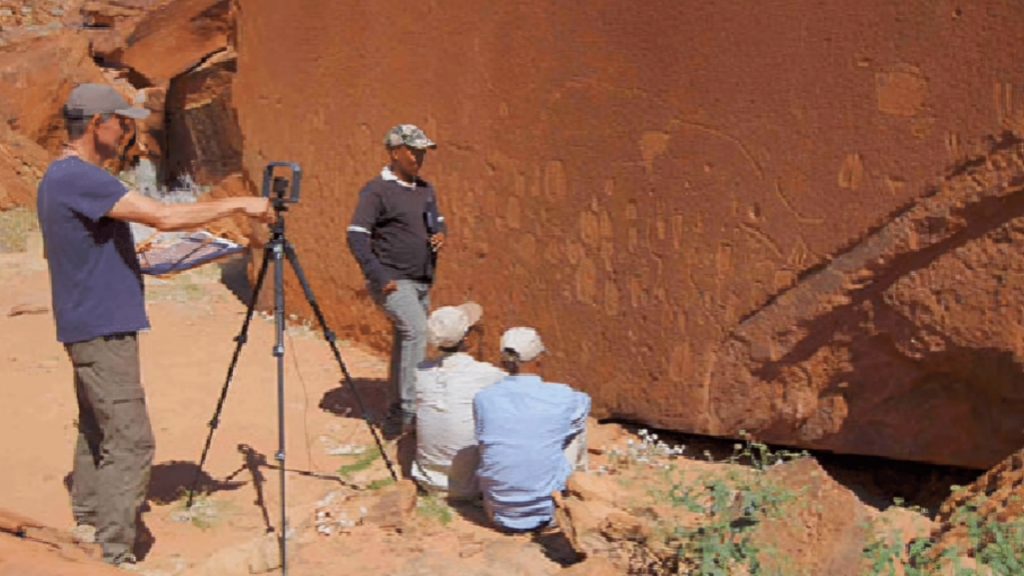

Pastoors and his colleagues, Thorsten Uthmeier from the Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nurnberg and Tilman Lenssen-Erz from the University of Cologne have been studying the footprint carvings in Namibia in hopes of learning why it was important to Stone Age people to record animal footprints … and to discover more about the incredibly accurate footprints.

A Thorough Study of the Prehistoric Carvings

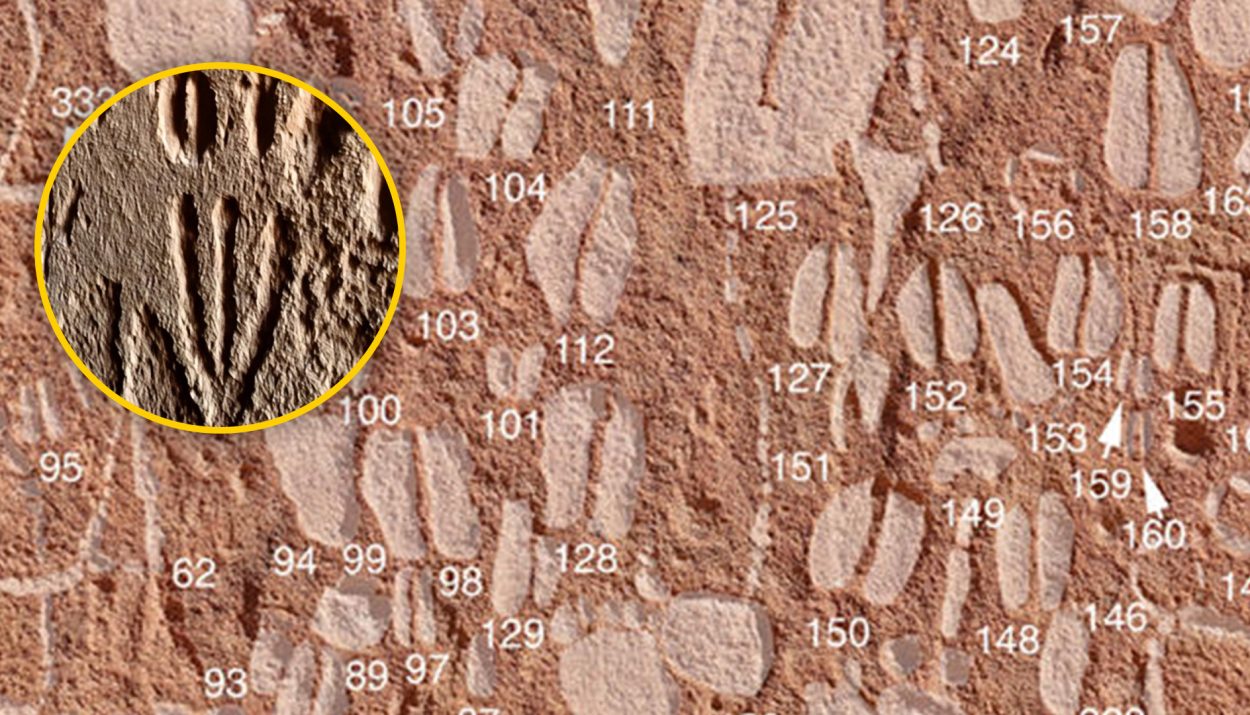

Pastoors, Uthmeier, and Lenssen-Erz have been working with the Nyae Nyae Conservancy, located in Tsumkwe, Namibia, to thoroughly study the recently discovered footprints carvings – all 513 of them – to see how they could be interpreted.

To assist them in their work, the German archaeologists recruited the help of three experts in animal tracks – Tsamgao Cique, Ui Kxunta, and Thui Thao. All three of these men are Namibian indigenous trackers and are affiliated with the Nyae Nyae Conservancy. They were tasked with applying their tracking skills to interpreting the prehistoric carvings.

Incredibly Accurate Details

Cique, Kxunta, and Thao examined the more than 500 carved footprints and, to the great surprise of the German archaeologists, were able to offer more information about them than expected. The trio of trackers were about to identify about 90% of the footprints, even those of animals that are not commonly found in the region today.

The footprint carvings were so detailed and clear that the trackers could pull additional information from them. For example, they could tell from the prints the approximate age of the animal and whether it was male or female. They could even differentiate between subspecies. For instance, they could discern prints belonging to white rhinos from those of a black rhino.

Dozens of Different Animals

Cique, Kxunta, and Thao identified nearly 40 different animal species depicted in the rock art based on their footprints. Springboks, giraffes, white rhinos, black rhinos, guinea fowl, and kudus made up the majority of the 513 footprints.

In addition to those, there were footprints from blue wildebeest, baboons, buffalo, and African wildcats, as well as monkeys, antelopes, and various birds. Only one footprint on the rock carving belonged to a cheetah.

Animals Not Common to the Area

One of the more amazing finds was that several of the animals included in the rock carvings were not common to the Doro Nawas Mountains or the surrounding plains. There were animals that could not thrive in the hot, dry desert. Many of the animals made their habitats in other parts of Namibia and neighboring regions.

For Pastoors and his fellow archaeologists, this raised some intriguing questions. How did prehistoric people know about these animals? How far did they travel during their hunts? Pastoors suggested, “It is plausible that the artists knew other regions with damper environmental conditions.”

A Breakdown of the Prints

Pastoors explained, “The engravings of animal tracks do not include generic forms; instead, each is specific.” Of all the tracks carved into the stone, 398 of them belong to fully grown, adult animals. Only 98 were from juvenile ones. There were more male animals represented than female ones.

Of the human footprints included in the carvings, nearly all of them belonged to children. Once again, more males – 74 prints – were depicted than females – 32 prints. The archaeologists do not know why only youngsters were included in the collection of footprints, but they noted that parents today save footprints and handprints of their children as mementos.

Why Were the Carvings Made?

Pastoors, Uthmeier, and Lenssen-Erz can only speculate as to why the detailed carvings were made. They theorize that they are “endowed with complex meanings” beyond what they have been able to glean with the help of the indigenous trackers. What those meanings are remains unclear.

Anthropologists and archaeologists believe that animal footprint art created by people in the Late Stone Age was encoded with messages we cannot interpret. For hunter-gatherers, rock art and cave drawings were the only means of recording information.

Were the Carvings a Teaching Tool?

Could it be that the animal footprints carved in the Doro Nawas Mountains were used as a reference guide or teaching tool? Was this how the next generation of hunters learned to identify their prey?

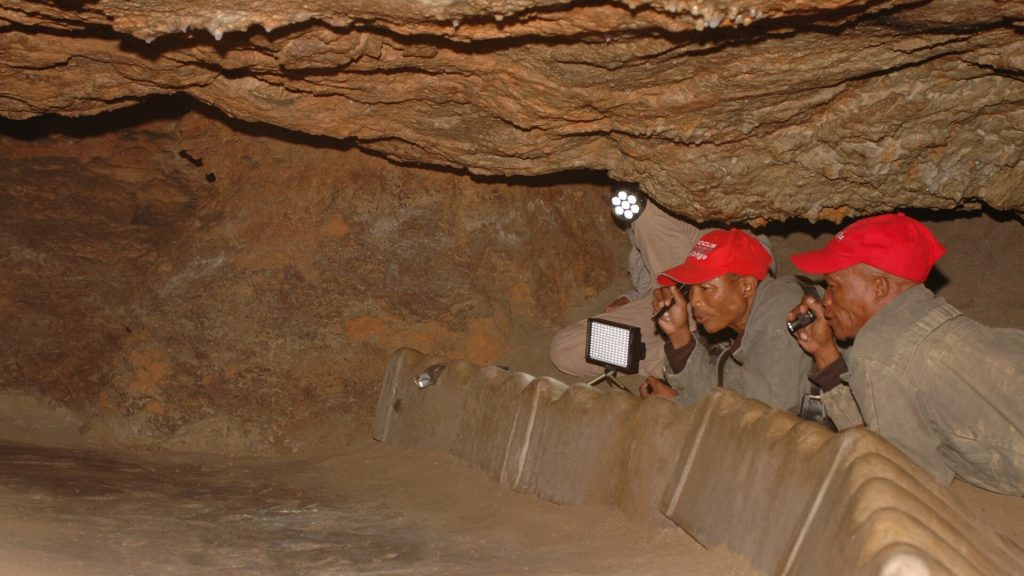

The idea that the engravings were used as an encyclopedia of knowledge, however, has been shot down by archaeologists. The carvings are situated in a dark area of the cave. Plus, they noted, most of the carvings are high on the cave walls. They would not have been easy for young children to see and study.

A Type of Language?

One theory that has been suggested is that animal footprint drawings and carvings were, in fact, a type of written language used by Stone Age societies. By comparing the rock art found in Namibia with those discovered in other areas, experts hope to look for patterns.

Pastoors, Uthmeier, and Lenssen-Erz intend to continue their study of the Namibia carved footprints. They are analyzing the arrangements, clusters, and groupings to see if they reveal insights into why the carvings were made.

Footprint Carvings … A Rarely Studied Field

According to Postoors, “The field (or archaeology) has completely disregarded the fact that tracks and trackways are a rich medium of information.” His colleague added, “Until now, (footprint rock drawings and carvings) have received little attention because researchers lacked the knowledge to interpret them.”

The German archaeologists hope their research will change this. Postoors said, “Attaining even an approximation … would require researchers to call upon ethnographic data and indigenous knowledge – a necessity of which future research would do well to take heed.”

Tapping into Indigenous Knowledge

Postoors is quick to acknowledge the invaluable contributions of the three Namibian indigenous trackers, Cique, Kxunta, and Thao. He added that these three men have assisted on other studies of prehistoric rock art and cave drawings in the past and have brought a unique perspective to the research.

In fact, he now strongly advocates tapping into indigenous knowledge as a resource tool to help archaeologists and anthropologists. He writes, “The study represents further confirmation that indigenous knowledge, with its profound insights into a range of particular fields, has the capacity to considerably advance archaeological research.”