Monticello, the historic home of Founding Father Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, was a labor of love for Jefferson. He devoted much of his time and energy into designing the magnificent home. “Architecture is my delight,” Jefferson once confessed, calling it “one of my favorite amusements”.

The Little Room With A Big Secret

Thomas Jefferson’s abilities as an architect served him well when he added a small, windowless room adjacent to his bedchamber. This room had been hidden from view since the mid-1900s when a modern bathroom was added for guests and employees at the historic attraction.

But when renovations were recently done, this space was rediscovered. But why did Jefferson include it? What was it used for? The answers to these questions were quite scandalous at the time and controversial today.

Hiding a Forbidden Romance

The small, secluded room, historians speculate, was the secret living quarters of Jefferson’s lover, the woman who shared his bed and bore him a half dozen children following the death of his wife. A lot of widowers find love in the second act of their lives, so why would Jefferson feel the need to keep his new romantic partner hidden from view?

Thomas Jefferson’s lover was Sally Hemings, one of his slaves. In the early 1800s, an interracial couple was such a shocking and scandalous thing that they would not be accepted in society. Jefferson would have been ostracized. His political and legal careers would have been over, and no one would have done business with his plantation. Keeping the relationship a closely guarded secret would have been the only option available to Jefferson and Hemings.

Keeping His Lover Close

The small room, which measured 13 feet long and nearly 15 feet wide, was the likely living quarters of Sally Hemings. The only way to access the room was through Jefferson’s personal chambers. It seems as though Jefferson designed this space for the sole purpose of keeping his lover close by.

Monticello’s director of archeology, Fraser Neiman, led the study on the hidden room. He was able to uncover the original floors, fireplace, brick hearth, and brick base for a stove. It sheds light on the life of Hemings and makes her place in Thomas Jefferson’s story more compelling.

Thomas Jefferson’s Dual Careers

A lawyer, scholar, philosopher, diplomat, statesman and primary author of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson is best known for work he did in the early years of the country’s government. He served as George Washington’s Secretary of State and John Adams’ Vice President, before he was elected to the nation’s highest office himself.

When he was not dabbling in politics, Jefferson practiced law. In 1767, after completing his formal education, he was admitted to the bar association of Virginia. Like many wealthy, prominent Virginians during that time, he owned a vast plantation and a collection of slaves to work the fields.

Jefferson’s Complicated Relationship with Slavery

During his time as a young lawyer, Thomas Jefferson advocated for slavery reform. In fact, he penned legislation in 1769 that would grant individual slave owners the freedom to emancipate his slaves if he so desired, shifting power away from the state governments. Interestingly, however, Jefferson didn’t push for the passage of this legislation himself. He asked his cousin to campaign for its passage for him.

As a lawyer, Jefferson took on several cases in which enslaved people were suing their masters for their freedom. When arguing these cases, Jefferson references natural law, stating that each person has the right to liberty. In nearly all of the cases, the judge dismissed Jefferson’s argument and ruled against the slaves. On paper, Thomas Jefferson appeared to be against the institute of slavery … yet he owned slaves himself.

Jefferson’s First Wife Made Him Vow to Never Remarry

Thomas Jefferson and Martha Wayles Skelton, a distant cousin and a young widow, were married in 1772. Martha was well-read and intelligent … a good match for the brainy Jefferson. The couple had six children together, although only two of them, daughters Patsy and Polly, lived to adulthood.

Martha Jefferson’s health declined, especially after the birth of her last child. As she lay on her death bed with her husband at her side, Martha made Jefferson promise he would not remarry. Martha lost her own mother when she was young and grew up with two different stepmothers. She did not want her children to be raised by strangers who did not love them. Distraught and eager to ease his dying wife’s mind, Jefferson agreed to remain unmarried. Martha Jefferson died in September 1782.

So, Who Was Sally Hemings?

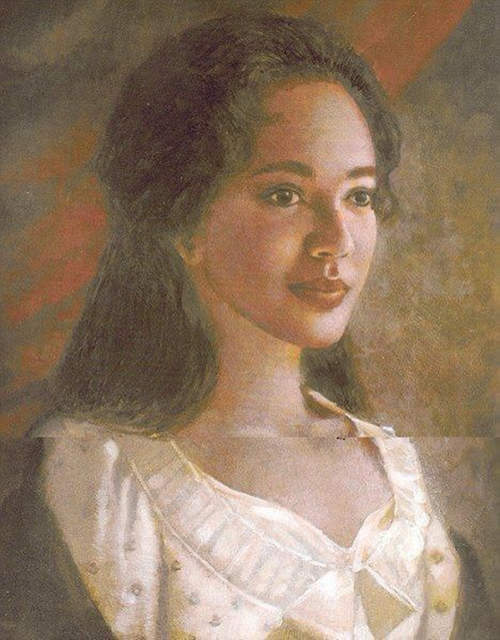

Even though Sally Hemings was a slave who was owned by Thomas Jefferson, she was only one-quarter black. She had one grandparent who was of African heritage. A description of Hemings from her day noted that she was “mighty near white”. But in the antebellum South, that didn’t matter. The small amount of African blood was enough to keep her enslaved.

To complicate things even more, Sally Hemings was Martha Jefferson’s half-sister. Martha’s father, John Wayles, fathered Sally when he had an affair with her mother, Betty Hemings, a slave who was owned by Wayles. It does not seem, however, that John Wayles and Betty Hemings were in a long-term relationship. Sadly, many white male slave owners treated their female slaves like concubines.

Sally Hemings Was Underage When She Started a Love Affair with Thomas Jefferson

In 1784, about five years after the death of his wife, the Congress of the Confederation sent Thomas Jefferson to France to join fellow Founding Fathers Benjamin Franklin and John Adams who were there on diplomatic assignments. He took his older daughter, Patsy, with him. Three years later, in June 1787, he sent for his younger daughter, Polly. Accompanying her on the voyage was 14-year-old Sally Hemings.

Sally Hemings stayed in Paris with the Jefferson family for more than two years. During that time, she and the 44-year-old Thomas Jefferson started a sexual relationship and Sally became pregnant. It seemed that Jefferson was more concerned about Sally’s African heritage than he was with their age difference.

In France, Sally Hemings Was a Free Woman

During this time period, slavery was outlawed in France. Slaves brought into France by American slave owners were not recognized as being owned by a master. Sally Hemings was technically a free woman when she lived in France. She had the right to remain there instead of returning to her life as a slave in the United States. Yet she didn’t.

The widely told story is that Sally agreed to return to the U.S. with Jefferson and live as a slave once again, but only after he promised to grant her child freedom when she reached the age of 18. When Sally bore more children for Jefferson, this agreement also applied to them. But there could be another side to the story. It could be that Sally had no means to support herself had she remained in Paris. It could also be that, as a woman in the late 1700s, she did not feel as though she could assert her rights.

Back to the U.S. and a Little Room at Monticello

When Thomas Jefferson and his entourage returned to his Monticello plantation in Virginia, he continued his relationship with Sally Hemings. It was at this time that Jefferson moved Sally into the small chamber adjacent to his bedroom where, it was assumed, he had easy access to his lover.

While small and sparse, the secret room likely had all the creature comforts Sally needed … a warm fireplace, a comfortable bed, a rocking chair to lull her baby to sleep. It is equally likely, however, that she did not spend a lot of time in this room. During the day, she had work to do around the mansion – according to Monticello’s records, she was a lady’s maid, seamstress, and nursemaid companion. In the evening, she may have shared Jefferson’s bed.

A Long-Lasting Romance

All evidence points to a long and fruitful relationship between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings. Sadly, Sally’s first child, two-year-old Harriet, who was born in Paris, died not long after the move back to Virginia. She bore five more children: William Beverely Hemmings, who lived from 1798 to 1873, Thenia, born in 1799 and died a short time later, Harriet II, who also died in infancy, was born in 1801, James Madison Hemings, who lived from 1805 to 1877, and Thomas Easton Jefferson, who lived from 1808 to 1856.

Jefferson was a meticulous recordkeeper and documented all the births of his slaves, noting both parents’ names. In the case of Sally Hemings’s children, he did not record the father’s name. DNA analysis of the offspring of Hemings’s children proves that all of her children were fathered by Thomas Jefferson.

The Jefferson-Hemings Affair Was Outed by a Disgruntled Journalist

The sexual relationship between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings was not the best-kept secret. Certainly, there were whispers around the halls of Monticello as well as throughout the well-connected social circles of Virginia’s wealthy elite. It was even publicized in a series of articles in the Richmond Recorder, written by journalist James T. Callendar, and caused a temporary scandal. James T. Callendar had a reputation for being a “scandalmonger” who attacked political enemies with scathing, sensationalized articles.

At one point, Callendar asked Thomas Jefferson to appoint him to the position of Postmaster of Richmond. When Jefferson refused, Callendar informed him that “there will be consequences.” Beginning on September 1, 1802, Callendar published a series of racially charged articles outing Jefferson for his relationship with Hemings. He called Hemings a “concubine” and noted that one of Sally’s sons strongly resembled Thomas Jefferson. The revelation caused outrage and was used by Jefferson’s opponents to question his fitness for political office. For his part, Jefferson refused to acknowledge the scandal and never publicly responded to it. Eventually, the scandal subsided, in part because Callendar’s reputation for printing wildly sensational stories cast a shadow over the validity of his claim.

Was the Relationship between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings Consensual?

While it might be romantic to view the relationship between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings as a tale of forbidden love and how the couple bucked traditions and ignored scorn to be together, there is another possible scenario … one that paints Jefferson as a perpetrator. Historians have wondered whether the relationship between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings was consensual. After all, there were two different dynamics at play: master and slave, and middle-aged widower and teenage girl.

It is a sad truth that many white, male slave owners took their pick of young, unwilling girls from their collection of slaves for their sexual pleasure. Sally Hemings’s father, as we learned earlier, was a white plantation owner, and father of Jefferson’s first wife. He impregnated Sally’s mother in an act that could be described as rape. This happened in plantations across the South and was common knowledge among white society. As long as men were discreet, everyone looked the other way.

Was Sally Hemings Groomed?

Accounts of the time tell us that Sally Hemings was quite attractive, however she was barely a woman when her relationship with Thomas Jefferson began. As a young, enslaved, partially Black female, she would have had to obey the orders of Jefferson, her older, whiter, male master. That is simply how the dynamics worked in those days.

It is possible that Jefferson groomed the pretty young Sally to be his lover. It is possible that the relationship was not consensual, and that Sally was the victim of ongoing sexual abuse. It is possible that Sally Hemings was, by definition, Thomas Jefferson’s concubine … one he kept in a secret room next door, so he had easy access to her whenever he needed his sexual needs met.

Sally Hemings, No Longer in Hiding

The historians at Monticello have chosen to recognize and celebrate Sally Hemings and her role in the life of Thomas Jefferson, however controversial or complicated that role may have been. Now that the secret room has been rediscovered, it is open to the public and part of the tour of Monticello. In addition to seeing the room itself, visitors to Jefferson’s historic home can also learn about the lives of slaves during Jefferson’s era and his complex views on slavery.

Thanks to DNA analysis, many of Sally Hemings’ living descendants have been found. They, together with the Monticello historians, are committed to shining a light on her life. The discovery of her hidden room adds another layer to our understanding of slavery in post-Revolutionary War America. As Sally Hemings has shown us from across the decades, slavery was not a simple, black-and-white issue.