The Great Wall of China is a marvel of human engineering and a beloved icon of China. The stone fortification wall, which once stretched from more than 13,000 miles across China’s northern-most border, was constructed over many years, going back as far as 2,200 years ago.

Experts often express concern that the historic Great Wall may deteriorate due to erosion. Although it is made of stone, the destructive forces of wind and rain can damage the ancient structure. A recent discovery, however, has shown that time has a tiny ally fighting against the ravishes of erosion.

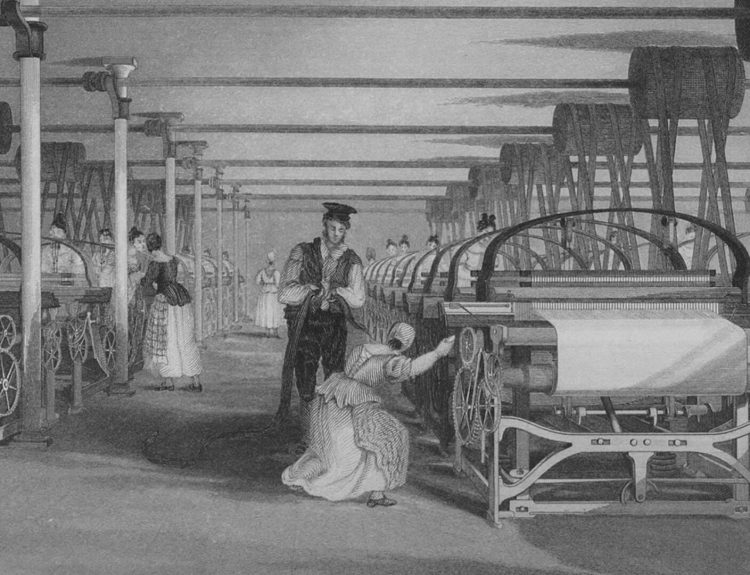

Building China’s Massive Border Wall

The Great Wall of China was constructed over several centuries and dynasties. The initial efforts to build defensive walls date back to the 7th century BC, but the most well-known sections were built during the Ming Dynasty, between 1368 and 1644 AD. The Ming rulers recognized the strategic importance of a northern defense against invading nomadic tribes, particularly the Mongols.

Emperor Qin Shi Huang, in the 3rd century BC, is often credited with the earliest large-scale construction, but it was during the Ming Dynasty that the wall assumed its more recognizable form. The wall featured watchtowers, garrison stations, and signal towers for communication. The construction involved a massive labor force, including soldiers, peasants, and prisoners.

Many Parts of the Great Wall Have Been Lost

While significant sections of the Great Wall of China remain well-preserved and attract millions of visitors annually, large portions have succumbed to the effects of time, natural forces, and human activities. Estimates suggest that approximately 20% of the original Ming-era wall still stands today.

Weather is not the only factor contributing to the demise of the Great Wall. During various historical periods, local communities repurposed wall materials for construction projects, and in more recent times, unregulated tourism and graffiti have contributed to degradation. Ongoing conservation initiatives strive to protect and preserve the Great Wall’s cultural and historical significance.

Battling Against Erosion

Large parts of the Great Wall of China were constructed using the rammed earth construction method. This involves mixing wet soil, gravel, clay, and organic material and ramming this mixture into a frame or mold. Once it hardens, the compressed aggregate forms solid structures.

Although walls made using the rammed earth method are durable, over time, they are vulnerable to erosion. The dried compacted material can lose its bond and crumble. Northern China experiences freeze-thaw cycles that contribute to the breakdown of material in much the same way that potholes are formed on asphalt roads.

An Unexpected Ally

Scientists studying the effects of erosion on the Great Wall of China, however, have discovered that Mother Nature has given them an unexpected ally in the fight against Mother Nature. The Great Wall of China may be one of the largest manmade structures on Earth, but this ally is extremely tiny.

Don’t let the size of this unexpected ally fool you. It only needs a few centimeters to hold off the destruction of the weather, forming a force field-like barrier to divert the wind and rain. Just what is this tiny, unexpected ally? Biocrust!

What Is Biocrust?

Biocrust, short for biological soil crust, is a living community of mosses, lichens, algae, bacteria, and fungi that covers the surface of soil and rock. Also known as cryptogamic or microbiotic crust, biocrust plays a crucial role in preventing erosion.

These moss and lichen organisms work together to form a complex network that binds soil particles and creates a protective layer. Researchers have learned that many parts of the Great Wall of China are at less risk of erosion than previously thought, thanks to the biocrust.

A Living Barrier

The rammed earth and stone that were used in the construction of the Great Wall of China provide the ideal environment for living organisms, especially ones that form biocrusts. In return, the moss and lichen retain moisture to keep the aggregate mixture from drying and crumbling.

The organisms also secrete polymer-like substances that serve as natural binding agents. These substances hold soil, gravel, and organic matter together. According to scientist Bo Xiao, “These cementitious substances … form a cohesive network with strong mechanical strength and stability against external erosion.”

Just How Strong Is the Biocrust?

To test the capability and strength of the biocrusts on the Great Wall of China, scientists conducted an experiment. They compared sections of the wall that were covered in biocrust with sections where no biocrust was present. Samples were taken from multiple portions of the wall, spanning a 300-mile area.

Along this 300-mile section of the wall, the researchers confirmed that two-thirds of it was covered with naturally forming biocrust. The difference between the biocrust covered portions and the bare portions was remarkable.

A Marked Increase in Stability

The biocrust-covered sections of the Great Wall were visibly different. They appeared stronger and more stable. The biocrust protects the cracks and pores, preventing water from seeping in and halting the destructive freeze-thaw cycle that greatly contributes to erosion.

According to Xiao, “Compared with bare rammed earth, the biocrust-covered sections exhibited reduced porosity, water-holding capacity, erodibility, and salinity by 2 to 48%, while increasing compressive strength, penetration resistance, shear strength, and aggregate stability by 37 to 321%.”

Giving Scientists Hope

While Xiao’s report observed that only 5.8% of the Great Wall of China can be labeled “Well-preserved” and that more than half of the original structure had either been completely destroyed or is in a state of severe deterioration. This would be dismal news for the icon structure if it weren’t for the discovery of the biocrust.

Now that scientists have a better understanding of how biocrusts can protect the earth rammed portions of the wall, they have hope for the preservation future of the iconic Great Wall. The thin layer of lichen and moss may not look like much, but it is a key tool in the battle against nature.