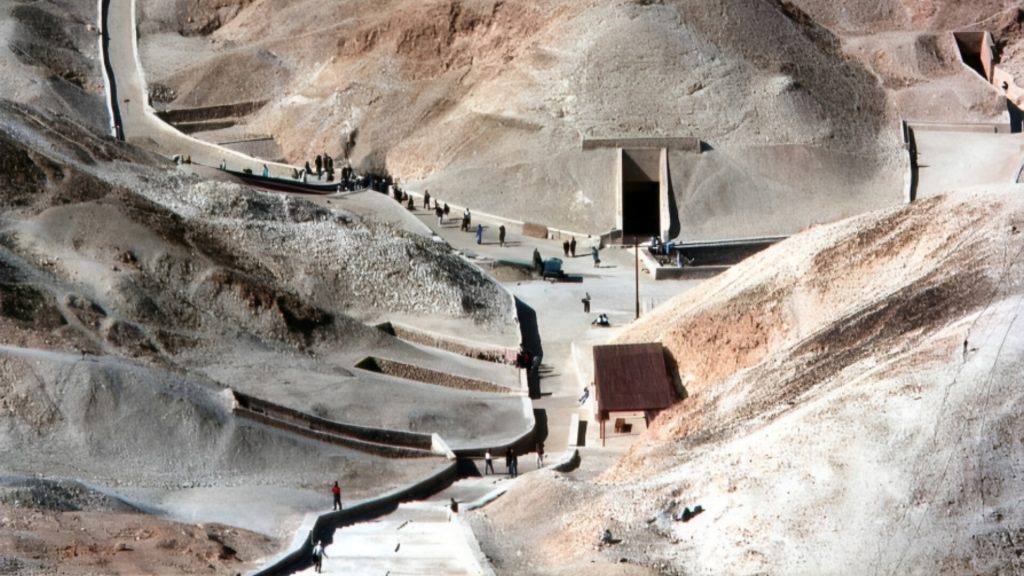

The sands of Egypt hold a plethora of wonders for history buffs, not least of all the tombs in the Valley of Kings. Some of these tombs, like the one named KV64, have their own unique mysteries. In this post, we’ll examine what this mystery is, why it happened, and learn about what it tells us about the past.

A Remarkable Discovery

KV64 was discovered by accident when researchers attempted to install a protective iron cover over a shaft in another tomb, KV40. When scientists found the shaft, they thought it was just another embalming shaft or an unfinished one that led nowhere. It was only one meter by two meters (3.3 ft by 6.6 ft) in size.

Further research showed that the shaft was actually the entrance to a new tomb, and it was officially given its designation and announced to the public in January 2012. Yet, on entering the tomb, what scientists found there baffled them to no end.

The Mystery Of The Twin Burial

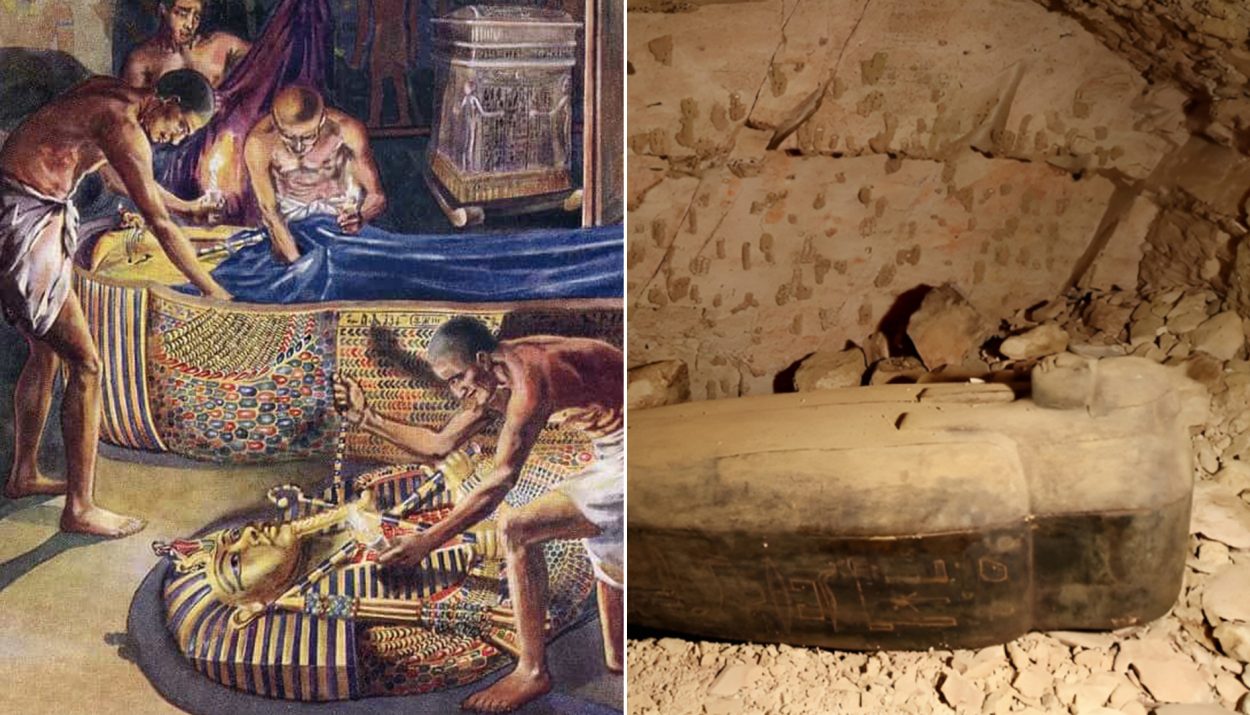

KV64 is a unique tomb in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. Inside, it holds two bodies, each interred 500 years apart. As is typical, the tomb was raided in the past, long before modern archeologists could explore it. Yet the tomb robbers seemed different from what we’re used to seeing.

Instead of breaking into both sarcophagi and taking all they could carry, only one of the two burials was opened up and robbed. The other one was left in pristine condition. Was this because of some curse on the body? Or did something else lead these tomb robbers to leave it alone?

A Small Tomb With a Strange Premise

Tomb robbers are nothing new – many of the tombs discovered in the Valley of the Kings were already raided when archaeologists got to them. Most of the grave robbers for these tombs came from much later periods, well past Ancient Egypt’s end. It was a capital sin in Ancient Egypt to raid the tomb of a former king.

The suspicious thing about this tomb is that it was discovered being used at a time when it was thought the Valley of Kings was no longer in use. The untouched sarcophagus was hundreds of years older than the desecrated one. This suggested that the desecration may have happened before the second sarcophagus was placed there.

Who’s Buried in KV64?

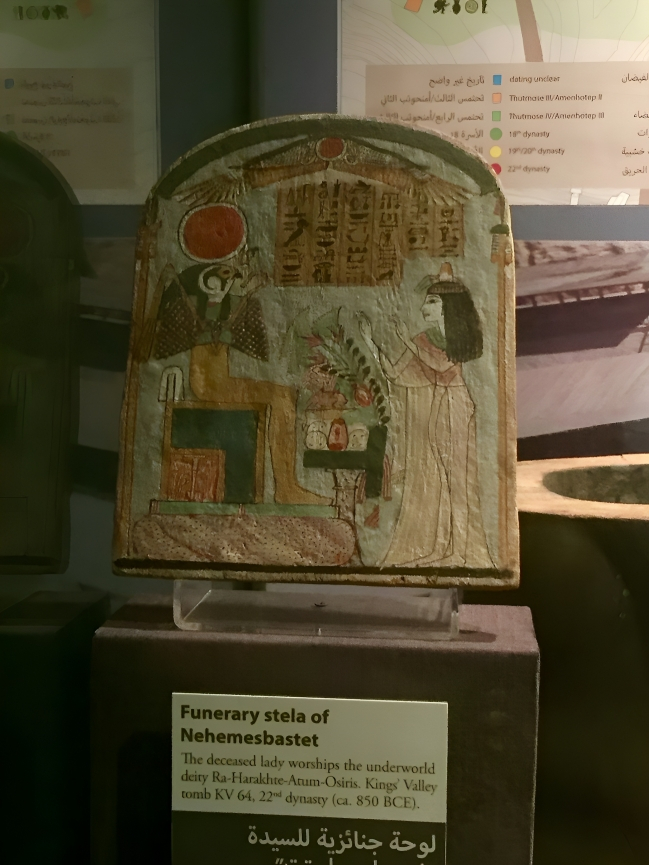

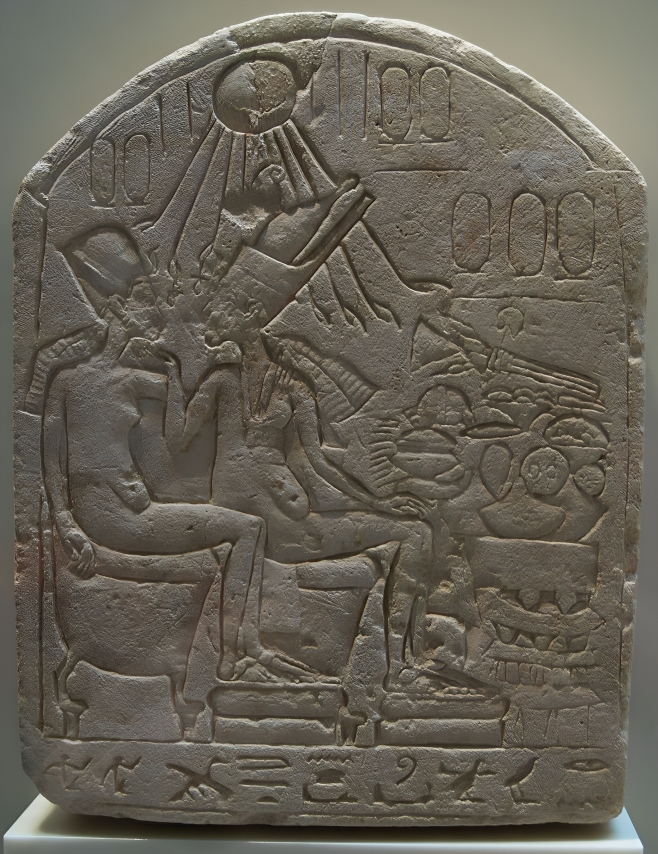

Based on the burial stele found inside the tomb, we can say for sure that the body that remained intact belonged to a woman named Nehmes Bastet. According to the stele, Nehmes Bastet was a chantress or a singer. Near to her stood the remains of the second occupant of the tomb.

There is little information on the second occupant, aside from the fact that she was buried in the 18th dynasty. A partial wooden label bearing the name “Princess Satiah” was found, but there’s no clue whether this referred to the Royal Lady of the 18th dynasty or not. Scattered around the tomb were the remains of the tomb-robbing.

A Period Of Easy Access

Archaeological studies into KV64 note that the tomb was opened up before it was resealed with Nehmes Bastet’s sarcophagus. Within the tomb were several wasp nests, suggesting that the animals had easy access to the burial chamber. Water-washed debris was also found on the floor of the tomb, suggesting its state.

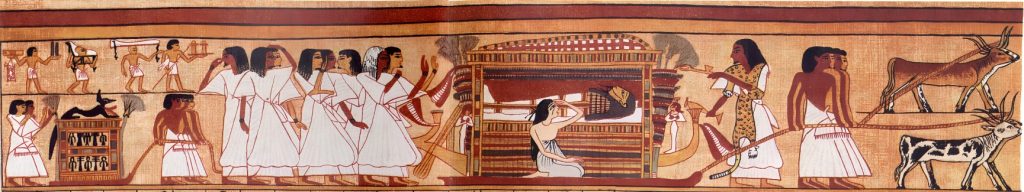

The area around Nehmes Bastet’s sarcophagus was littered with the robbery of the previous inhabitant of the tomb. Scientists discovered fragments of canopic jars, pieces of coffins, furniture parts, glass, and the broken, unwrapped mummy of the Royal Lady of the 18th dynasty.

A Period of Political Upheaval

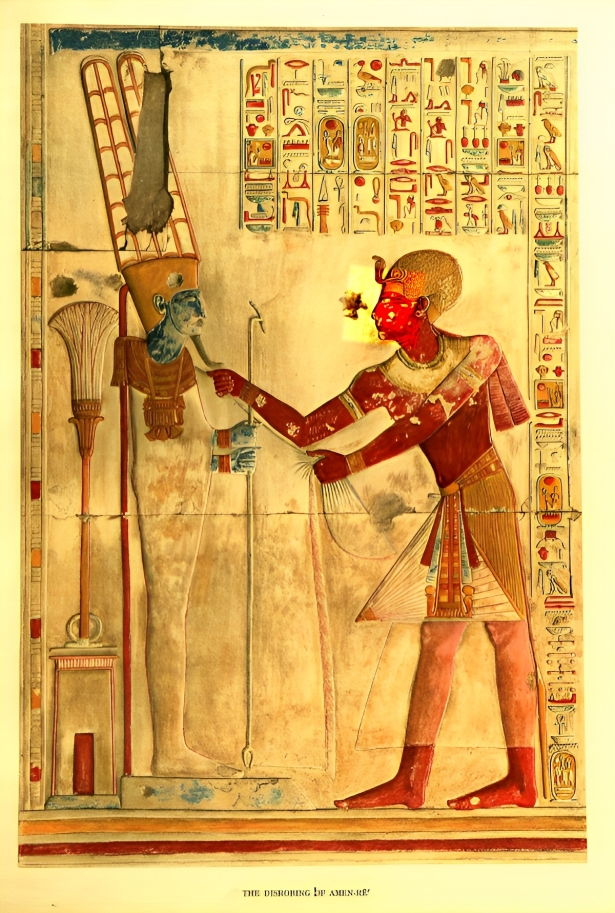

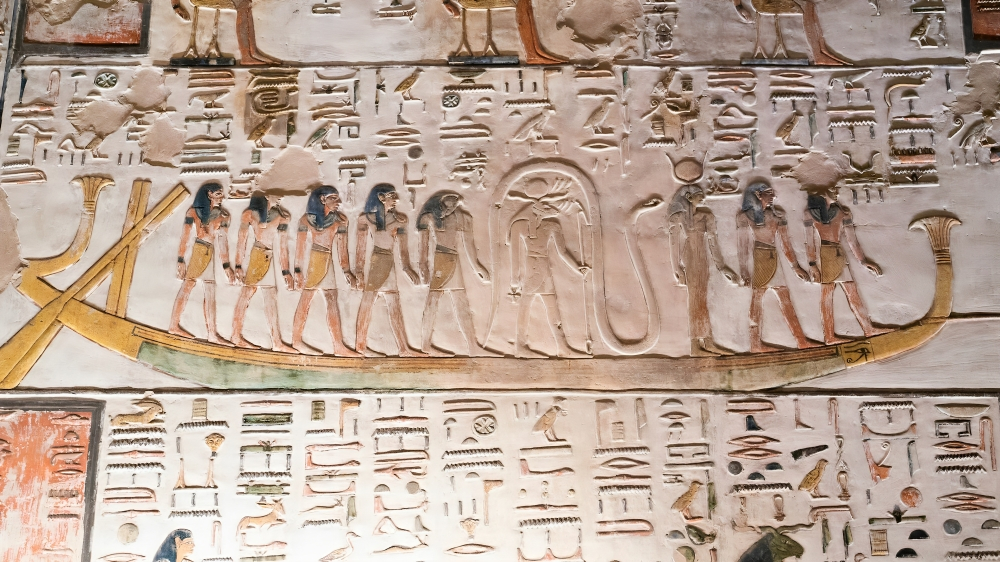

Egypt is known for how long it was a force in the ancient world. By the time the 18th dynasty happened, the religious faction within Egypt was gathering power. Amenhotep, the high priest of Amun, was responsible for all the wealth flowing from the god’s temples into Egypt.

However, between the 18th and the 21st dynasties, things changed drastically. This era, known as the Third Intermediate Period, saw pharaohs spending money as if there were no tomorrow. By around 1000 B.C., the wealth of Egypt was being strewn about by leaders who had no idea how to spend it. The pleas of the priests were brushed aside.

A Change In Leadership

The 18th dynasty saw the rise of leaders like Akhenaten, who moved away from the traditional polytheistic nature of Egypt and transformed it into a monotheistic kingdom. This, of course, rubbed the priests of Amun the wrong way. Who was Akhenaten to replace them overnight?

Tutankhamun succeeded Akhenaten to the throne and immediately rescinded the changes that he made. Here was a ruler that would restore tradition to Egypt, the priests thought. Except, he didn’t at all. He restored some of the old religion but spent so much that the empire’s coffers ran bare.

A Female “King” Might Have Been the Last Straw

The records of rulers following Tutankhamun are sketchy, with some carvings indicating a female ruler. It’s not certain that this woman was Nefertiti since her reign was so short. Yet, for the traditionalist priests of Amun, this was an unacceptable state of affairs.

To soothe the egos of these priests, Nefertiti relocated her capital back to the priestly center of Thebes. This didn’t go as far in helping her become more recognized by the priests, and they saw it as a drastic change. Too extreme for them to put up with.

What’s a Priest To Do?

Of course, the priests wouldn’t take this challenge lying down and rose up to oppose the pharaohs. To avoid conflict, pharaohs started moving their capitals and taking followers with them. This led to even less income from the temples of Amun, further reducing Ancient Egypt’s wealth.

The change in capital from Luxor to Tanis in the north meant a new regime in Northern Egypt. The economic situation of the priests changed drastically, and so they decided to strike back in a unique way – desecrate the tomb of someone they considered to be an enemy.

Not A Decision Taken Lightly

It was more than just frowned upon to raid the burial mounds of royalty or priests in Ancient Egypt. Yet, with dwindling income from their temples and the royal line pitted against them, ignoring their advice and destroying their legacy, they took it upon themselves to “kill two birds with one stone.”

There is no record of who the second tomb belongs to, and the desecration was so violent that it seemed to have been personal. Archaeologists know that the person in the grave was a woman and probably a member of the royal line. Whoever robbed the Royal Lady of the 18th dynasty did it during this tumultuous time.

A Hate Crime In Ancient Egypt

Women were a significant part of ancient Egypt but primarily served in subservient roles. Some made it into the priesthood or acted as influential factors in temples. Nehmes Bastet is an excellent example of a powerful woman.

Yet the priest’s problem wasn’t with powerful women. It was with powerful women of the ruling house. Maybe it was to teach Nefertiti a lesson by desecrating the remains of her ancestors, or perhaps it was hate for a royal woman that led to this destruction.

A Window Into A Secret Past

When we think about recorded history, Egypt typically falls into the category of a well-documented empire. Yet, some things happened there that we still know nothing about. The Third Intermediate Period is one of those epochs we have little information on.

The rulers of Lower Egypt at the time, the priests, didn’t record what they did to refill their coffers. Yet, based on the state of the Royal Lady of the 18th dynasty’s remains, we can be sure it involved breaking into the tombs of royalty they knew about and stealing whatever wasn’t nailed down.

A Relatively New Look On An Ancient Tomb

Scientists knew about the Third Intermediate Period and its political upheaval. They also knew about the rise of the priests of Amun and the establishment of the Lower Egyptian Kingdom. However, many archaeologists didn’t consider that it played a part in KV64’s mystery for a long time.

Only after scientists ascertained that the tomb had remained unopened for over 3,000 years did a picture begin to form. Since the tomb was closed off for so long, a modern grave robber can’t gain access to it. This suggests that the priests did the tomb-robbing before Nehmes Bastet was interred.

What This Tells Us About The Egyptian Upheaval

While history has a general overview of what caused the movement of the pharaoh’s capital from Luxor, we still don’t understand the establishment of the Lower Egyptian Kingdom so well. We also don’t know much of what happened behind the scenes.

Desecrating a royal grave was punishable by death in Ancient Egypt. These tombs were kept as sacred monuments, suggesting that the priests who destroyed the tomb and the mummy did so out of hate and anger. It shows how deeply their conviction ran and how disgusted they were with their leadership.

Learning More Every Day

The Valley of the Kings holds some sixty or so tombs we know of, but new graves are being discovered occasionally. Each vault contains more information about ancient Egypt and its people and rulers spanning thousands of years.

With each discovery, we learn a little bit more about what those people knew or felt. We discover a little more about their lives and their fears. And every now and again, we encounter grave-robbing priests trying to fund a start-up kingdom in Lower Egypt by stealing from tombs.