Along the western coast of Ireland, we find the famous Cliffs of Moher. Roughly five miles long and reaching heights of more than 700 feet, these stunning sandstone and shale cliffs mark the point where Ireland meets the Atlantic Ocean. A popular tourist destination, the Cliffs of Moher are much more than a dramatic panoramic location.

The Cliffs of Moher are a vital home to coastal seabirds and a wonder of geography. They are also, as a recent discovery reminds us, a trove of paleontological finds dating back millions of years. In fact, a new fossil found at the Cliffs of Moher turned out to be a new species.

Ireland During the Carboniferous Period

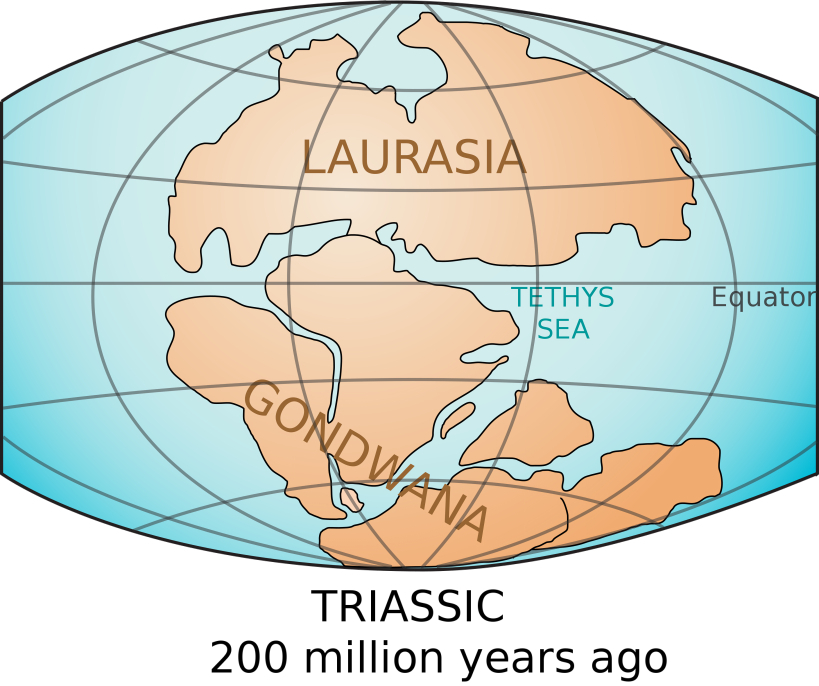

During the Carboniferous Period, roughly 315 million years ago, the landmass that is now Ireland was part of Pangaea, the supercontinent. Ireland was closer to the Equator at this time. The warm, humid climate was ideal for lush, primitive plants and sea animals. In fact, the abundant plant life and dense vegetation during the Carboniferous Period became the great coal deposits in Ireland.

Over the span of millions of years, Ireland’s landscape was molded by rising sea levels, geological uplifts, and erosion. The remains of prehistoric plant and animal species were buried under layers of sediment. Many of them have been found by paleontologists and amateur fossil hunters.

Ireland Was Once Part of Two Continents

As the supercontinent Pangaea broke apart and landmasses spread apart on continental plates, the Earth looked vastly different than it does today. Ireland, scientists have been able to determine, was once part of two different ancient continents … Laurentia and Gondwana. These two landmasses were separated by the waters of Iapetus, a prehistoric ocean.

Ireland’s northern half was once part of Laurentia. Parts of Laurentia survive today in what is now North America. The southern half of Ireland, including the area where the Cliff of Moher is located, belonged to Gondwana. As Gondwana further broke apart and drifted, it became Europe, parts of Africa, and Australia.

How the Cliffs of Moher Were Formed

The Cliffs of Moher, like Ireland itself, date back some 320 million years to the Carboniferous Period. The visible horizontal layers on the face show that the cliff is made of bands of sandstone, siltstone, rock, and shale. They were deposited by sediment carried over the area by ancient rivers.

The different layers of material have different densities. Some erode more readily than others, which gives the Cliffs of Moher their distinct appearance. It also makes them a dangerous place. Visitors are advised not to stand on the edge of the cliff or climb onto ledges. They could give way at any time, sending a person into the ice Atlantic below.

A Fossilized Sponge?

Although it may not sound as sexy as a fossilized dinosaur, the recent discovery of a fossilized sponge at the Cliffs of Moher is quite significant from a geological and paleontological standpoint. The sponge, once a living organism, is approximately 315 million years old.

As you now know, that date coincides with the time when Ireland was part of the landmass of Pangaea, the supercontinent. Its position near the Equator made it a prime habitat for tropical sea sponges. Sponges, as we will see momentarily, are impressive and unique animals. But that’s not what made this fossilized find so special.

The Wonderful World of Sponges

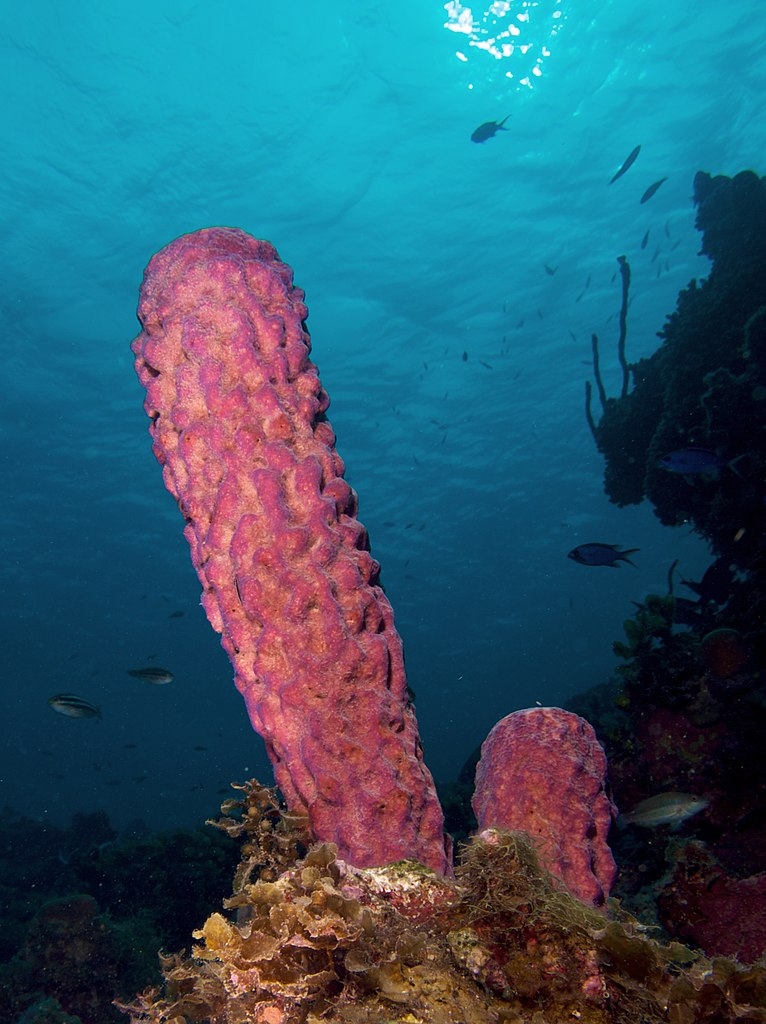

Sponges may seem like simple, unassuming sea animals, but they are uniquely adapted for their environment … and have been for millions of years. Sponges are filter feeders. They absorb water through their porous bodies and pull out the minute nutrients they need from the water. This method has served the sponge family well for more than 600 million years.

Biologists list sponges as one of the earliest members of the animal kingdom. They have thrived in the Earth’s oceans, nearly unchanged, through the planet’s numerous geological eras. In fact, one of the secrets to their longevity as a species could be their simplicity. Another could be that sponges contribute to the health of their ecosystem by filtering the water.

Sponges Serve as a Benchmark for Paleontologists

As a common, yet primitive animal, sponges serve as a benchmark for paleontologists and researchers studying the evolution of animal life on Earth and the role of evolutionary adaptations. Even though sponges lack organs, digestive systems, and brains, they can provide researchers with valuable insight into the conditions that led to the creation of more complex life forms.

Sponges also have astonishing regenerative abilities. By studying these, scientists can learn more about how Earth’s earliest life forms survived the changing environment. Sponges are true living fossils. Because they have evolved so little over time, they offer a tool to compare the evolutionary journey of other animals.

Sponges, Big and Small

Biologists have classified about 5,000 known species of sponges living today. The vast majority of these live in the world’s saltwater oceans, but a handful – about 150 species – make their homes in freshwater. Sponges come in all shapes and sizes. The smallest sponges are roughly one inch in size.

Some species of sponges, however, can grow to be quite large. It is not uncommon to find sponges that are about six feet in length. The largest recorded living sponge was recently discovered in Hawaii’s Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument. It measures 12 feet by 7 feet … or about the size of a minivan!

Ireland’s Sponge Fossil Is the Largest One of Its Kind

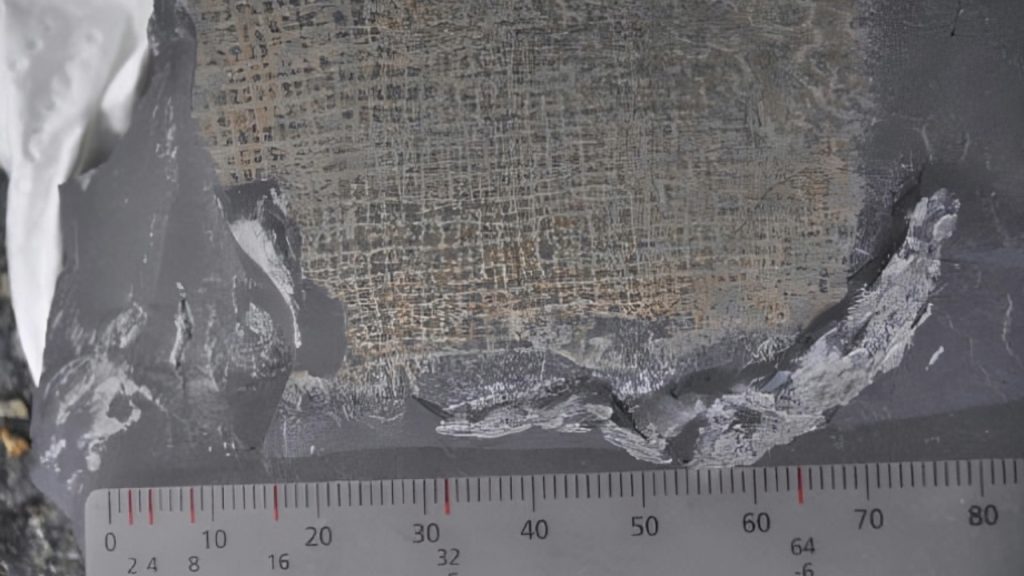

Although the recently discovered sponge fossil at the Cliffs of Moher is just under two-feet tall, it is the largest known sponge fossil of its kind. It also represents a previously unknown species of sponge, one of the earliest known members of the sponge family.

According to Dr. Earmon Doyle, a geologist working for the Burren and Cliffs of Moher UNESCO Global Geopark, “This is an exceptionally large example of a family of fossil sponges that were previously only known from much older rocks elsewhere in the world. It is the first record of this family of fossil sponges from Ireland.”

Dr. Doyle’s Chance Discovery

It was Dr. Doyle himself who made the amazing fossil find. But he wasn’t really looking for prehistoric fossils. He was actually looking for some flagstones for his patio when he chanced upon the fossil. Fortunately, he recognized the discovery for what it was.

Dr. Doyle immediately contacted Dr. Joseph Botting in nearby Wales. Dr. Botting is an international expert on fossilized sponges … just the person to call! Dr. Doyle snapped a few photos of the fossil with his cell phone and texted them to Dr. Botting. When he saw the pics, Dr. Botting dropped what he was doing and flew to Ireland.

Naming the Newly Found Sponge Species

After Dr. Botting confirmed that this fossil indeed represented a new sponge species, the next step was to name this species. The genus name, Cyathophycus, was chosen because this sponge species was a member of that ancient family.

For its species name, it was decided to select a name with Irish roots, to honor the location of its discovery. This sponge, when it was alive, had a round opening surrounded by a ring of thin, cilia-like features. It reminded the researchers of eye lashes. That gave them the inspiration for the species name … balori.

The Mythical Irish Balor

Like the Greek Cyclopes, Balor is a one-eyed character in Irish mythology. Balor’s eye, however, has magical destructive powers that can destroy towns and smite onlookers. The only way to stop Balor’s cataclysmic gaze was to blind him.

The single, eye-like feature is the only similarity between the Cyathophycus balori sponge. Balor was described as a demon-like monster associated with chaos and calamity. The sponge lacks these abilities, of course.

A Well-Preserved Fossil

Dr. Doyle was particularly thrilled to find such a well-preserved fossil. “Its excellent preservation is highly unusual,” He explained. “The sponge was originally composed of a rectangular meshwork of tiny spicules made of silica, held together by a thin organic membrane.”

Dr. Doyle further added, “When they died, they usually fall apart quickly, and often only scattered remains of the spicules are preserved as fossils – so I was delighted to find these largely intact specimens.”

The “Wonderful Geological Legacy” of the Cliffs of Moher

According to Dr. Botting, “Discoveries like this help us promote awareness about the wonderful geological legacy we have on our own doorstep.” He further noted that discoveries such as this one help to create excitement about the field of paleontology and encourage a whole new generation of paleontologists.

He agreed with Dr. Doyle that the state of preservation of the sponge was remarkable. “This was totally unexpected,” he said. “This find offers important insights into the evolution of sponges and how some species can survive in niche environments where few other species can live. Finding such large and intact specimens is exceptional.”

An Added Attraction at the Cliffs of Moher

The fossilized sponge will remain close to the location where it was hidden for millions of years. For Dr. Doyle, it was important to keep the historic fossil at the Cliffs of Moher to show visitors the geological significance of the site.

While credit for the discovery of the fossilized sponge goes to Dr. Doyle, Dr. Botting, along with his co-author Dr. Lucy Muir, published their report on the new Cyathophycus balori sponge in Geobios, a well-respected international geology journal.