Chinese leader Mao Zedong had what he thought was a sure-fire plan to boost the Chinese economy in the mid-1900s. His plan, which he called the Great Leap Forward, included the audacious goal of ridding the whole country of some pesky and destructive pests.

One of the pests on Mao’s hit list was sparrows. Unfortunately, Mao didn’t think things through and, apparently, none of his advisers wanted to speak up about the plan. The eradication of the sparrows had unexpected and devastating ramifications in China. Let’s see how.

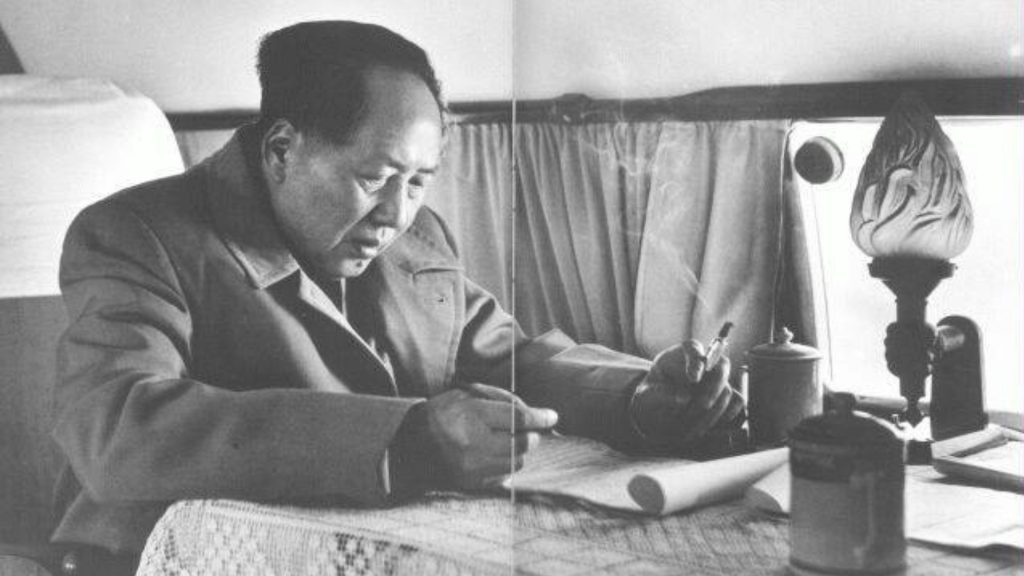

Who Was Mao Zedong?

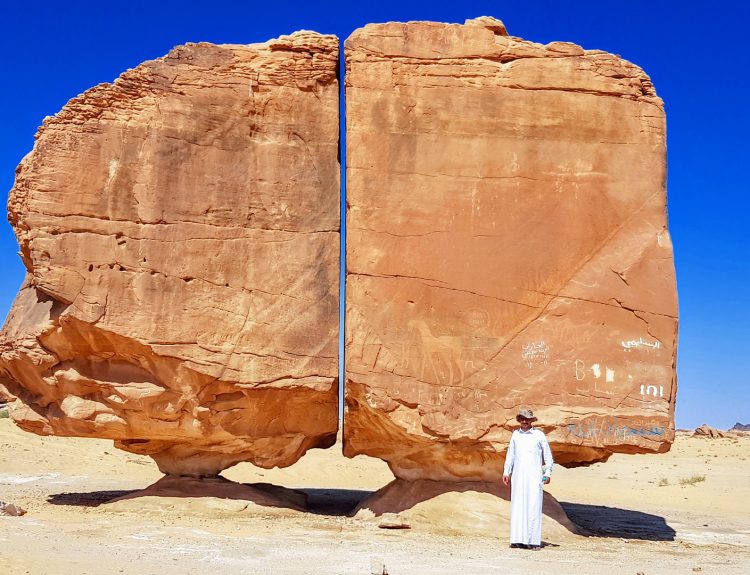

From 1943 to 1976, Mao Zedong served as the Chairman of the Communist Party of China, a position that really meant he was the leader of the whole country. Mao had lofty goals for his country. He was determined to see China catch up with other nations, such as the United States and the United Kingdom in terms of technology, manufacturing, and agriculture.

In the 1950s, Mao introduced a five-year plan – actually his second five-year plan – which he dubbed the Great Leap Forward. To accomplish the Great Leap Forward, the people of China were asked to take radical and aggressive steps to streamline various industries and make the country run more efficiently.

The Great Leap Forward’s Industrial Goals

Mao Zedong’s hope was to turn China into an industrial powerhouse that surpassed the output of Britain. Initially, he set a 15-year deadline to reach this goal. Then he changed it to one year – an impossible goal.

When people protested, Mao ordered them to be killed. When people tried to explain to him that he had set an unreasonable goal, Mao ordered them to be killed. Before the end of 1958, more than 5,000 people had been killed for speaking out against Mao’s unrealistic industrial goals.

Mao’s Agricultural Goals

As the most populous nation on the planet, China had a lot of mouths to feed. Mao believed that Chinese farmers should be able to produce all the food the Chinese people needed and have a sizable surplus to export.

Under Mao’s program, rural farmers had to relinquish their farmland to the government. The farmlands were merged together to form vast “agricultural cooperatives.” The farmers were then required to work on the government-owned communal farms for low wages and much smaller portions of the yield on which to feed their families.

Destroying the Land

Forests were cut down to create more farmland and to provide fuel for small-scale smelting operations. Mao requested that citizens set up their own smelting furnaces to reduce the country’s reliance on imported steel.

The large, communal agricultural land was over-farmed. The nutrients in the soil were depleted and there wasn’t a chance to replenish the soil. The crops struggled to grow. The depletion of the soil and the deforestation made the land susceptible to erosion.

Questionable Agricultural Practices

Mao made drastic changes to agricultural practices in China, which he believed would improve yield. In an effort to maximize land space, for example, Mao ordered plants to be planted closer together.

Unfortunately, like many of Mao’s initiatives, this was put into practice before it was tested. The plants, when too close together, didn’t get the nutrients they needed. The grain harvest decreased because of this practice. But it was not the worst part of Mao’s initiative.

Mao’s Four Pests Campaign

Mao Zedong believed that the key to increasing China’s agricultural output lies in pest control. He identified four pests that were detrimental to crop harvests – rats, flies, mosquitoes, and sparrows. His “Four Pests Campaign,” which started in 1958, targeted these four pests.

As part of Mao’s “Smash Sparrows Campaign,” Chinese citizens were commanded to kill as many sparrows as they could. They were ordered to shoot the birds, destroy their nests, smash their eggs, and kill hatchlings. The “Smash Sparrow Campaign” even suggested that people bang on pots and pans to scare the sparrows to death.

Mao Was Working with Faulty Intel

It might seem odd that Mao’s “Four Pests Campaign” targeted sparrows as we rarely think of them as crop-destroying pests. However, one of Mao’s advisors told him that sparrows ate grain. That was partially true. Sparrows do eat grain … but they also eat other things, like locusts.

No one wanted to set the record straight and explain to Mao that sparrows are, in fact, omnivores that rely on insects as a main part of their diets. As a result of Mao’s “Smash Sparrow Campaign,” more than one billion Eurasian tree sparrows were killed.

The Delicate Balance of Nature

Nature maintains a delicate balance. All living things within an ecosystem play a role in maintaining its equilibrium. That includes living things that we consider to be pests. If we remove one insect or animal from the equation, the entire system falls apart.

In the late 1950s, however, when Mao ordered the eradication of sparrows from China, he did not know about this complex web of life. He did not know that sparrows themselves act as an agent of pest control by eating insects.

Without Sparrows, Locust Populations Increased

Sparrows have a varied diet, but one of their favorite food items – locusts – have a very limited diet. Locusts only eat grain. Without sparrows around to keep the locust population in check, the insects quickly multiplied.

Like the Biblical plagues, great swarms of locusts descended on the farm fields of China, devouring the crops. The unnatural imbalance in the ecosystem was one of the contributing factors to the Great Chinese Famine.

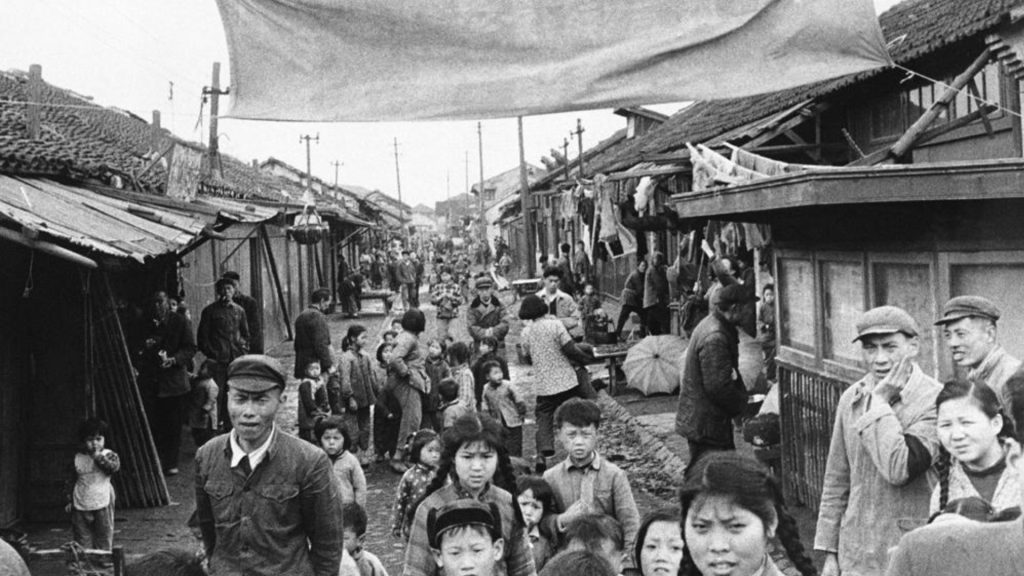

The Great Chinese Famine

Between 1959 and 1961, China’s agricultural communes underperformed. Crops failed. Harvests were destroyed, Flooding and erosion wiped out yields. The combination of unwise farming practices and the loss of natural pest control agents created a food shortage.

Instead of being transparent about the crop failures and subsequent food shortage, Mao’s government exaggerated crop yield reports and downplayed the famine. The Chinese citizens were confused by this. They knew the truth.

Covering Up the Famine

The people living in the Chinese countryside were hit especially hard by the Great Chinese Famine. These rural farmers were used to having the freedom to grow their own food. Now they toiled long hours on the government’s agricultural communes but came home empty handed to face their starving families.

Mao, however, was a proud leader. Asking other nations for help feeding his people, to him, was a sign of failure and his own shortcomings as a leader. He would rather see his people starve to death than to ask for help.

Maintaining the Charade

To maintain the charade and downplay the famine, Mao continued to export what little grain they had. By falsifying crop yield reports and continuing to export grain, Mao was able to keep the rest of the world from knowing the true extent of the famine.

Even after the famine ended in 1961, Mao and his government continued to downplay the disaster. They refused to call it a “famine.” Instead, they used the term “three years of difficulty” to describe this period in Chinese history.

Heartbreaking Stories of Desperation Emerged from the Famine

Tales of heartbreaking desperation emerged from the Great Chinese Famine that are difficult to hear and unfathomable to understand. There were reports of parents who were so overwhelmed by the cries and pleading of their young children that they did the unthinkable.

Parents, according to stories, took their youngsters into the mountains and abandoned them there. They left their own children to die of exposure in the wild rather than watch them starve to death before their eyes. The horrors of the famine didn’t stop there.

Families Faced Agonizing Decisions

As the food ran low, families were faced with making some impossible and agonizing decisions. The elderly and infants were left to starve first so that food could be given to other, stronger members of the family.

Even while facing the realities of famine, Chinese families were concerned about preserving the family name of the next generation. Therefore, sons were given more food to sustain them, while daughters were underfed.

Reversing the Crop Failures

Once Mao halted the “Smash Sparrow Campaign” in 1960, the sparrows returned to rural China. The birds kept the insect population from getting out of control. Slowly, crop yields improved and the famine eased.

China still prefers to keep their head in the sand regarding the famine and Mao’s failed “Great Leap Forward” policies. For the rest of the world, the Great Chinese Famine is a stark reminder about the dangers of upsetting the balance of nature, as well as the dangers of hubris in political leaders.