The automotive industry and the poultry industries are two facets of economics that, on the face of it, don’t seem like they would have anything in common. You especially wouldn’t think that chickens would have any impact on the import or creation of different types of trucks, but that fact is very true, considering some interesting historical events.

Chicken as a Media Sensation

The poultry industry is one that has gotten a lot of press over the past several decades. Some of the press includes the monopoly of companies that produce and sell chicken, all the way down to how the chickens are raised from the get-go.

There’s a lot to be said for the policies that affect animal farmers and the policies that allow very few companies to control the poultry market. But a surprising policy regarding chickens has had a wider impact than merely what can be seen in the poultry market.

Surprising Outcomes of the Industrial Revolution

Early in the twentieth century, after the Industrial Revolution was in full swing, the United States developed methods for chicken farming that allowed them to raise and produce poultry very quickly, for very cheap. Naturally, this allowed for a great deal of profit to be made by the chicken farmers.

Poultry farming is a practice that has been happening for centuries. Chickens are part of the family of fowl that survived the extinction event that killed the dinosaurs, and domestication of chicken is a practice that has been traced back about 8,000 years to Southeast Asia, though the true origin of the domesticated chicken remains a controversial topic.

Chickens Are A Staple … Now

Chickens are known for their meat and eggs, and they are an animal that is slaughtered for food worldwide. In the United States alone, more than 8 billion chickens are slaughtered every year for meat, and more than 300 million chickens are raised each year for egg production.

The mass raising and production of chicken and eggs is a practice that can be traced back relatively recently, though. In the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth century, chicken and egg production was largely confined to family farms, though it was a widespread practice with nearly 90% of families having chickens.

Chickens Were Needed More and More

The urbanization of America increased demand for poultry and eggs. It wasn’t until the discovery of Vitamin D in the 1920’s that the practice of keeping chickens indoors and producing eggs and meat-year round became a common farm career.

Advancements in technology lowered the effort needed to breed and maintain chicken farms, allowing for the market to expand. Between the 1930’s and 1950’s, a full-time family farm could contain as many as 1500 chickens, but the rapidly changing economy soon changed the profitability of the venture.

A Worldwide Industry

By the 1950’s, the price of eggs had fallen drastically due to the commonality of the egg and chicken. Farmers began to keep two and three times the number of chickens in order to maintain their profit in the American market, and the business of family-owned chicken farms slowly began to transition to industrialization.

Newly industrial chicken farmers weren’t content to merely sell to an American market, though. They saw the whole world as a potential for profit on their cheap and fast chicken, and in the 1960’s American chicken farmers began to export their poultry to countries other than the United States.

European Farmers Suffered for American Ingenuity

The flood of American chicken into markets in Europe devastated the local poultry market. Chicken farmers in France and Germany were unable to match the price or the quantity of the chickens that were being exported from the United States. Almost overnight, the profit margin for these local farmers plummeted to near zero in the wake of the competition.

Of course, European policy makers weren’t going to stand by and ignore the suffering of their farmers. After a great deal of complaints regarding the cheap chicken being exported by the United States, the European Union instituted the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

A Drastic Policy Change

Agriculture is the only industry in the EU that has a common policy across all countries. CAP is a domestic farming policy that was formed under three principles. First, a unified market with common prices. Second, product preference for the internal market over foreign exports. And third, financial solidarity through common financing.

The intent of CAP was to create a fair income for local farmers, and to incentivize buying from local supply versus imports. In the process, it also placed tariffs on chicken imports, which had a rapid and devastating effect on the American chicken export business. Policymakers in the United States were, understandably, unhappy.

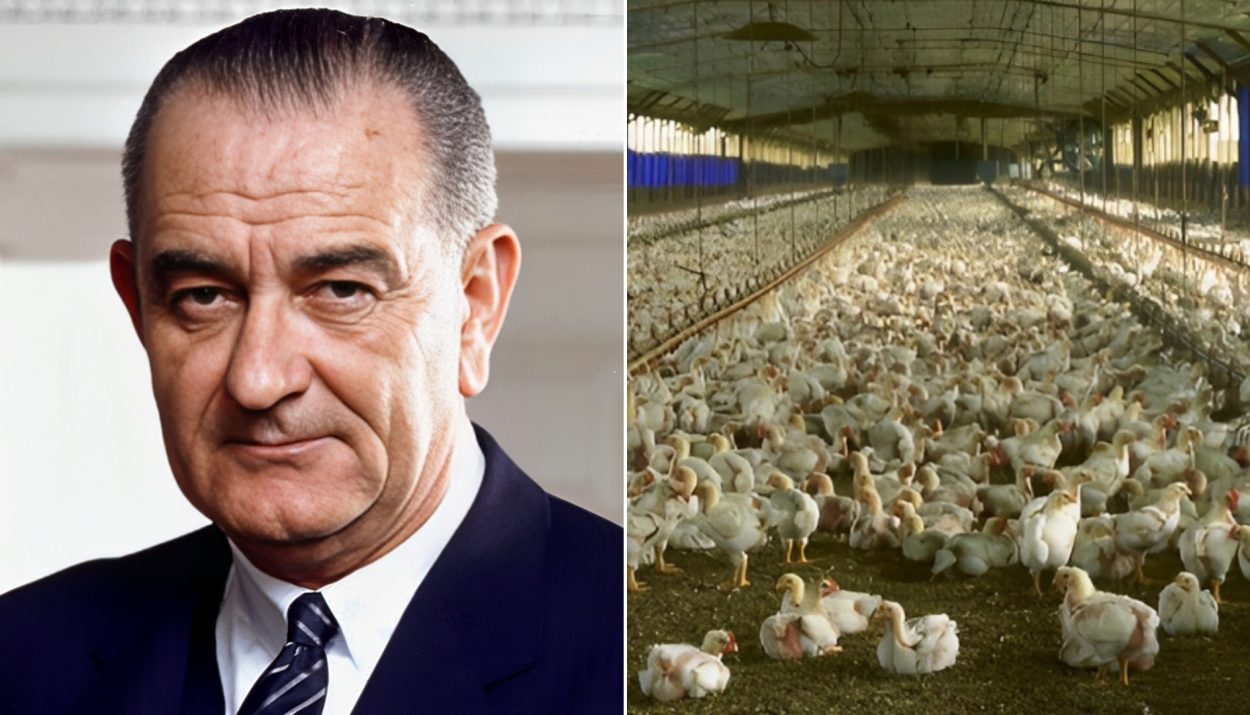

A Presidential Blow

In response to the blow to the chicken industry, current president of the United States Lyndon B. Johnson decided to retaliate with his own policy. Since chicken imports were being levied by tariffs from the European Union, he decided to place tariffs on a variety of goods that were imported from the EU.

A tariff, simply put, is a tax that is placed on foreign imports and exports. Tariffs have been levied many times in history, going all the way back to Ancient Greece. The intent of tariffs is often to raise more money for local governments, but it can also be used to make a point of policy, as is what happened with the Chicken Tax.

The Chicken Tax as a Policy

Initially, the chicken tax was placed on a variety of goods, including small trucks, potato starch, brandy, and dextrin. The policy went into effect early in 1964, and was formally intended to recoup the income that the United States lost when the EU placed its own tariff on the import of chicken.

In the background, though, tapes revealed later that there was a tit-for-tat agreement between Johnson and the president of the United Auto Workers union. If Johnson would institute policy to curb the import of German-built trucks, the union head would support his reelection campaign.

The Ultimate Effect Ignores Intent

Whether the intent was to punish the European Union or to support local automakers, the effect was all the same. European imports were suddenly taxed at a much higher rate, and domestic sales of those same products increased, much to the pleasure of local industry members.

After several years, the chicken tax was modified so that the tariffs no longer applied to brandy, dextrin, or potato starch. The tariff on foreign small truck imports remained, though, and has pursued up until modern day, a remnant of Cold War history that is now known as the “Chicken War.”

Automakers Both Benefit From, and Try to Ignore the Law

The modern existence of the Chicken Tax is one that has rankled many automakers, and has caused some to attempt to circumvent the law. Where small trucks imported from other countries are taxed at a higher rate, small trucks locally produced do not have to face the same fees.

Some automakers have gone to very creative lengths in order to get around the tariff. Japanese automakers, for instance, found that they could export “chassis cab” style vehicles for only a 4% tariff. Once the cab was located in the United States, the bed of the truck could be attached and the entire vehicle sold as a light truck. This loophole in the law was closed in 1980, though.

Japan Isn’t the Only Culprit

Foreign automakers are not the only ones who have tried to get around the tariff, either. Ford has attempted to circumvent the tariff several times over the past years. First-generation Transit Connect light trucks were manufactured in Turkey, where they were outfitted as passenger vehicles, allowing them to evade the tax.

Once the truck was in the United States, the rear seats were removed and destroyed to instate its “light truck” status, a process that cost Ford hundreds, but saved them thousands in tariff fees. This practice eventually came under scrutiny from Customs and Border Protection, drawing legal fire.

Ford vs. Customs and Border Protection

Ford became the focus of Customs and Border Protection in 2013 when they ruled that the imported Transit Connects should be taxed at the applicable 25% tariff rate for vans, due to the way they were being modified once in the country.

Ford sued CBP for the change in policy, attempting to protect the millions in profit that they were saving by not paying the small-truck tariff. The case dragged on for several years until 2020, when the Supreme Court declined to hear the case and affirmed CBP’s new guidelines.

Moving Forward Without the Chicken Tax

The fascinating history of the chicken tax reveals a part of domestic and foreign policy that many people don’t consider in our increasingly-small world. The choices that policy makers institute at home often have wide-ranging consequences that may not appear obvious from the beginning.

Challenges to the chicken tax are ongoing, with some lawmakers calling it a policy without reason. Where it may have had a point in the beginning, and even possibly some good intent, the fact remains that it is a law from an era that is long gone, and likely should be treated the same.