When Italy’s Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 A.D., it completely destroyed the Roman city of Pompeii and its smaller neighbor, Herculaneum. A thick layer of volcanic ash, pumice, and mud buried the two cities, preserving the homes, shops, and artwork.

The catastrophic eruption also preserved the extensive library of a Herculaneum scholar and philosopher, Philodemus. The scrolls in his collection – numbering more than 2,000 in total – contain a wealth of knowledge. There’s just one issue – how to read them.

Looking for Marble and Bronze, Not Paper

Charles VIII of Naples commissioned an excavation of a recently unearthed villa in the ruins of Herculaneum in 1752. People in Italy knew of the existence of the buried cities, but at this time, no formal excavations had been conducted. Charles VIII wasn’t particularly interested in the historic or archaeological value of the site.

Instead, he was looking for priceless artwork. Some of the grand villas of the once-prosperous cities had begun to yield artistic masterpieces. The king of Naples tasked his diggers to find him marble and bronze statues to add to his collection of Roman art.

A Room Full of Charred Lumps

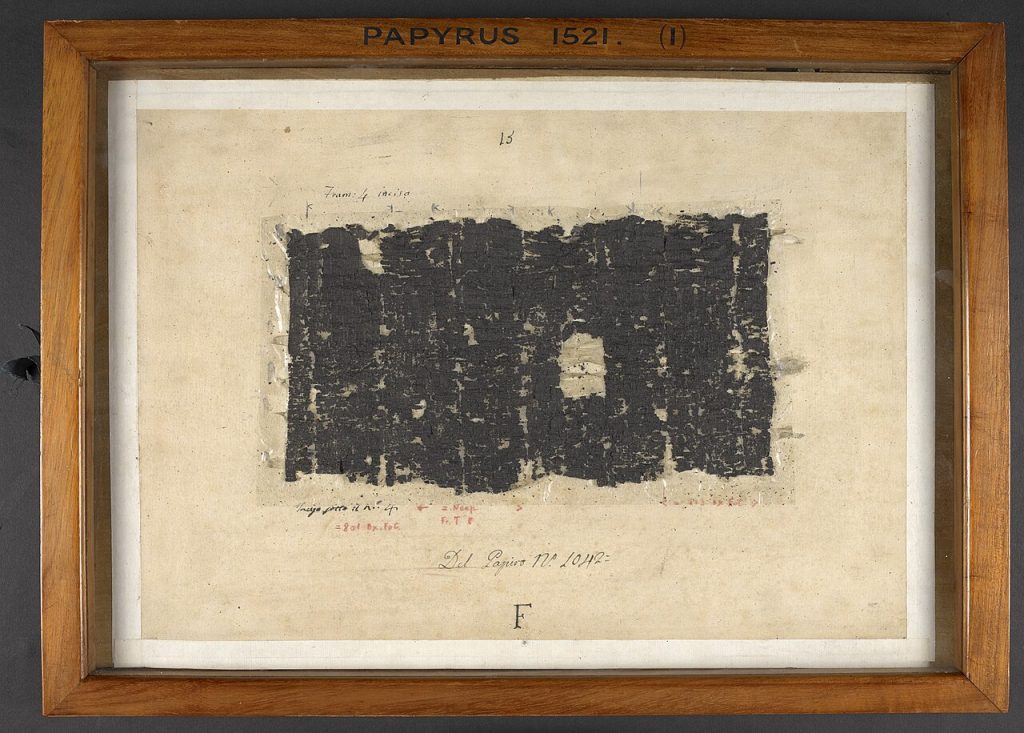

The king’s dig crew made their way into a separate room in the villa they were excavating, hoping to find a trove of statues. Instead, the room was filled with strange charred and blackened lumps. When the workers touched them, the lumps broke apart and disintegrated.

A few of the workers discovered that the burnt lumps were quite flammable. They made good fire starters when it came time to cook their meals. But the lumps seemed to be carefully arranged in the room. And there were so many of them. It dawned on them … these lumps were burnt scrolls. They had found an ancient library – the only complete library surviving from antiquity.

What Wonders of the Classical Era Could Be Found in the Scrolls?

During this period in European history, the late 1700s, people were fascinated by the ancient Greek and Roman cultures. The great philosophers of the Classical Era were venerated by contemporary scholars. The philosophers of old, they believed, were wise and astute. They had all the answers to life’s questions.

When King Charles VIII learned of the discovery of the library, he arranged for the fragile scrolls to be carefully transported to his personal library. He was eager for Camilla Paderni, the royal keeper of the king’s museum, to unroll the scrolls and read the ancient wisdom. But it wasn’t as easy as that.

An Impossible Task

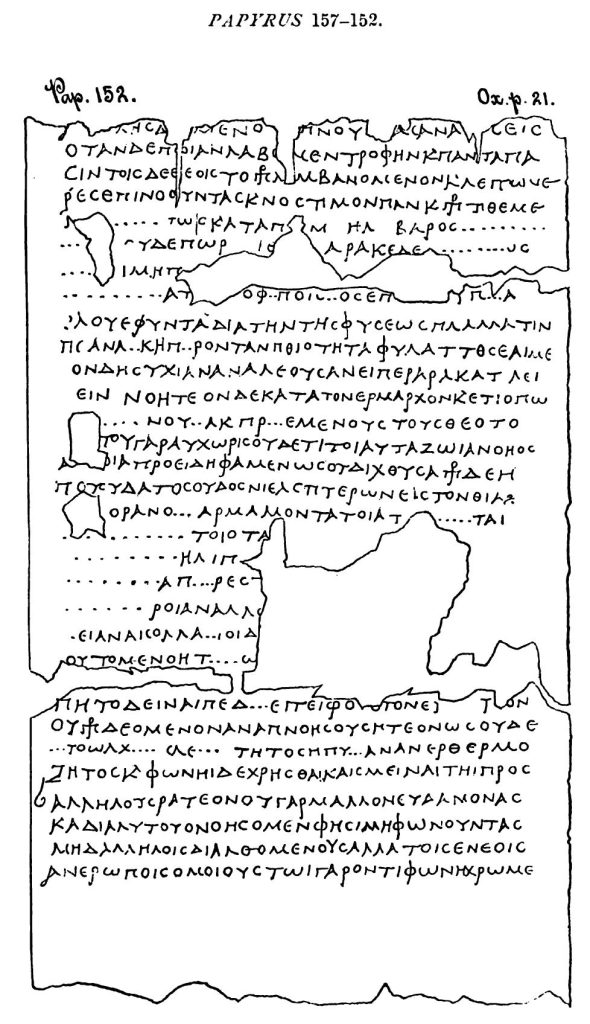

In a letter written at the time, Camilla Paderni discussed the challenges of reading the scrolls. He explained, “It is not a month ago, that there have been found many volumes of papirus, but turn’d to a sort of charcoal, so brittle, that, being touched, it falls readily into ashes.”

Despite the challenges, Paderni persisted, on the orders of Charles VIII. He wrote, “Nonetheless, by his majesty’s orders, I have made many trials to open them, but all to no purpose excepting some words, which I have picked out entire, where there are divers bits by which it appears in what manner the whole was written.”

Building an Unscrolling Machine

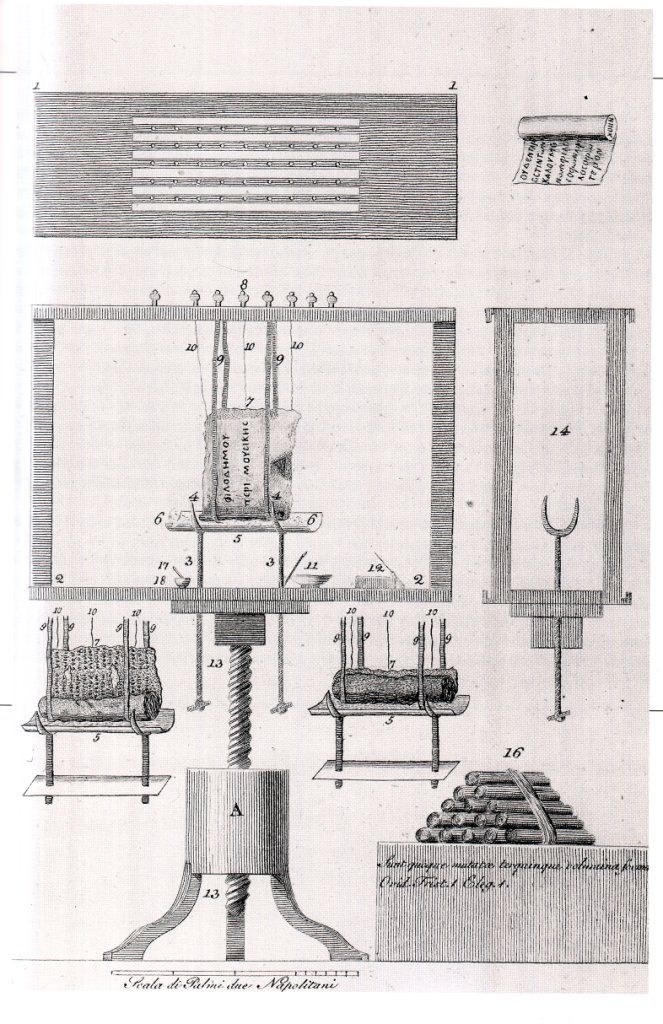

Since the carbonized papyrus was too fragile to unroll, one man attempted to build a machine to unroll the burnt scrolls. He was Antonio Piaggio and he served as the Vatican’s keeper of manuscripts.

The machine he developed in 1753 used a series of weights to slowly and meticulously unroll the scrolls. It was only a slight improvement over doing it by hand, but it gave scholars hope that, as science advanced, the knowledge written on the scrolls would someday be revealed.

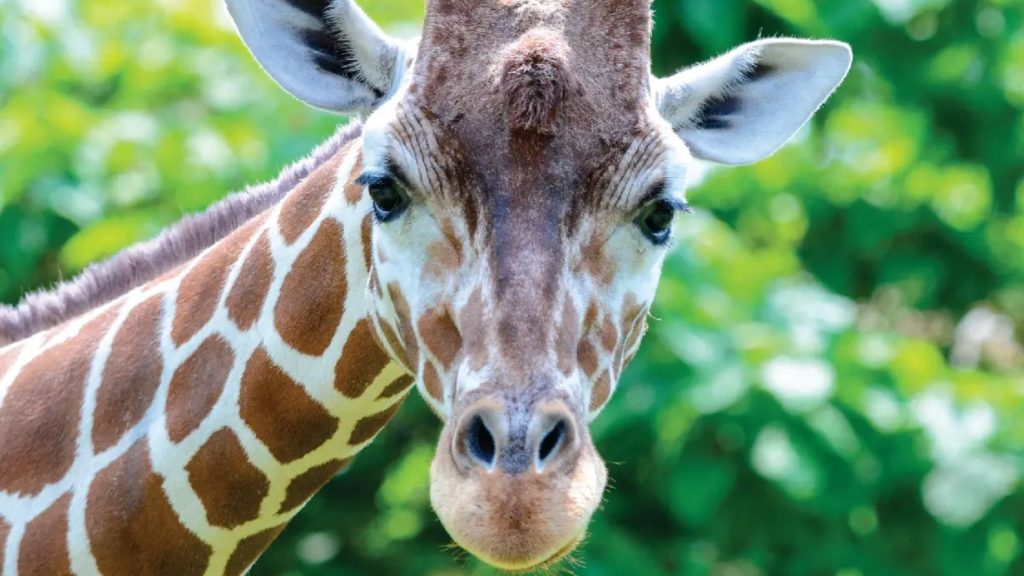

Trading Scrolls for a Giraffe … Seriously!

King Ferdinand IV of Naples agreed to an unorthodox trade in 1816. He would hand over several of the charred scrolls from the library of Herculaneum to the British in exchange for a giraffe. Yes, a giraffe. The king really wanted a giraffe to add to his menagerie of exotic animals.

The scrolls were entrusted to Dr. Friedrich Sickler who was both experienced in handling old Egyptian papyrus and had studied ancient languages. He soaked the scrolls in water. While this helped him unroll the scrolls, the water removed the ink. Sickler ruined seven of the dozen scrolls before the British parliament fired him.

Maybe Chemistry Held the Answer

Noted chemist Sir Humphry Davy took a crack at the Herculaneum scrolls. Compared to previous attempts, Davy’s approach was quite gentle. He took extreme care to preserve the scrolls, rather than destroy them.

Davy used acid, iodine, and chlorine vapors to release the layers and make the papyrus more pliable so they could be unrolled. The chlorine and iodine also changed the color of the paper, so the ink stood out more clearly.

What Do the Scrolls Say?

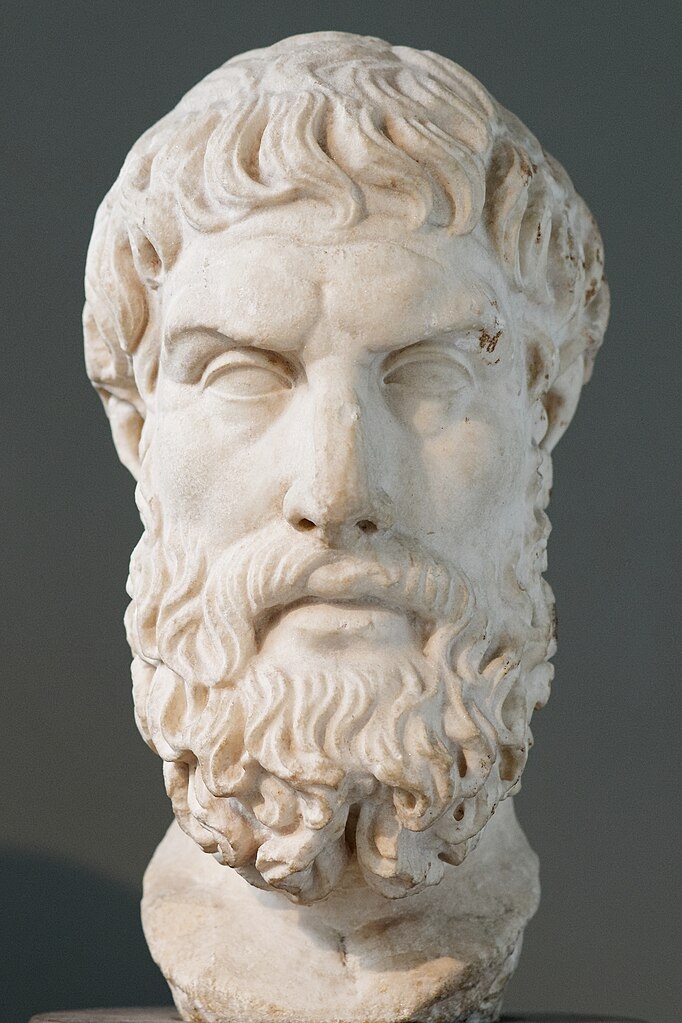

Philodemus, the Herculaneum scholar who amassed the library before Vesuvius erupted, was, according to the scrolls, a follower of the Roman Epicurean philosophy. Epicurus, who lived from 341 to 270 BCE, based his believe system on the idea that people should make the most of their lives, seek worldly pleasures, and embrace a hedonistic lifestyle.

His ideas were once common across the Roman Empire, but they fell out of favor with the rise of Christianity. Christianity preached that people should live moral lives so that they can enter the Kingdom of Heaven and find redemption.

Epicurus Advocated Living for the Moment

For centuries, scholars have eagerly awaited the time when the burnt scrolls from the library of Herculaneum could be read, and they could learn the knowledge and wisdom contained within them. As it turns out, the great secrets of life revealed in the scrolls are not unlike the lyrics of Bobby McFerrin’s hit 1989 song, “Don’t Worry, Be Happy.”

In one of the scrolls, for example, Philodemus, a follower of Epicurus, wrote, “Don’t fear god, Don’t worry about death; What is good is easy to get, What is terrible is easy to endure.”

The Scrolls Have Been Preserved

The scrolls from the library of Herculaneum are now stored in a safe, secure location with a stable, climate-controlled environment. No one is allowed to handle the fragile papyrus.

In recent years, however, digital scans of the scrolls have been made. This will allow scholars to continue studying the words of Philodemus and the philosophy he espoused during his lifetime in ancient Italy.