The story of Lynnewood Hall, a grand and stately residence in Elkin Park, a suburb of Philadelphia, in many ways, mirrors the meteoric rise and devastating fall of the Gilded Age. The sprawling home, which celebrated its completion with an extravagant gala on December 19, 1899, was a symbol of the economic prosperity of the industrial age, decades later, after two world wars and a nationwide depression, Lynnewood Hall fell into disrepair.

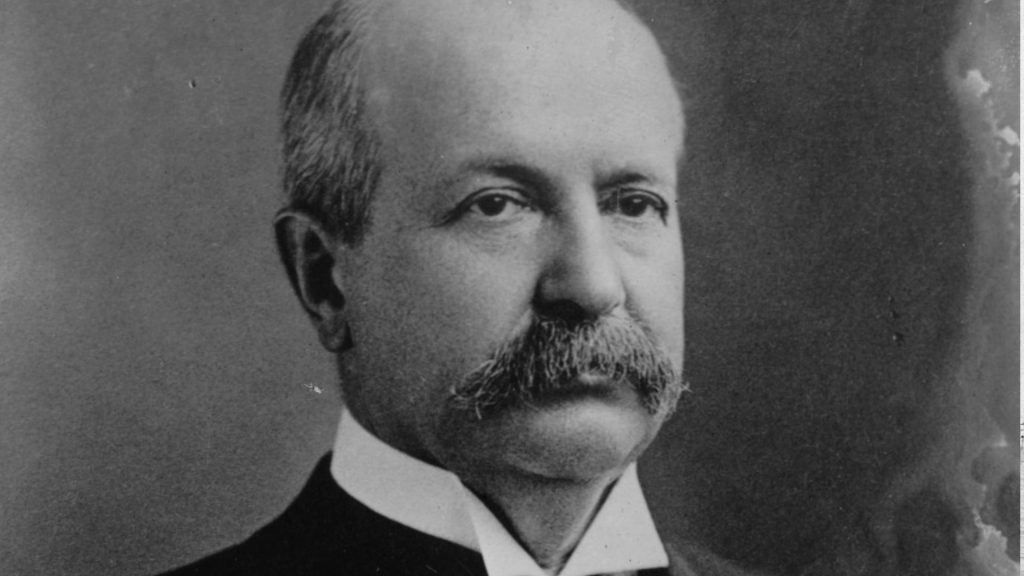

Yet Lynnewood Hall was built to withstand the test of time. Wealthy business owner Peter A.B. Widener, who amassed a sizable fortune in the streetcar and trolley industry, commissioned a talented, young architect named Horace Trumbauer to design and build a home that would impress his friends and business acquaintances.

A Pandering Architect

Horace Trumbauer was a young and up-and-coming architect when he designed his first major home, Grey Towers Castle, which was built in 1893 for businessman William Welsh Harrison. Peter A.B. Widener was jealous when he saw his friend Harrison’s new home. He wanted one just like it ….. only bigger and grander.

Trumbauer’s work on Lynnewood Hall kick-started his career. Despite designing a slew of elegant manors for Gilded Age industrialists, he was snubbed by his peers. He was viewed as a panderer who designed increasingly ostentatious homes to stroke the egos of new millionaires looking to flaunt their wealth and fortune. Today, however, Trumbauer is regarded as one of the premier architects of his day.

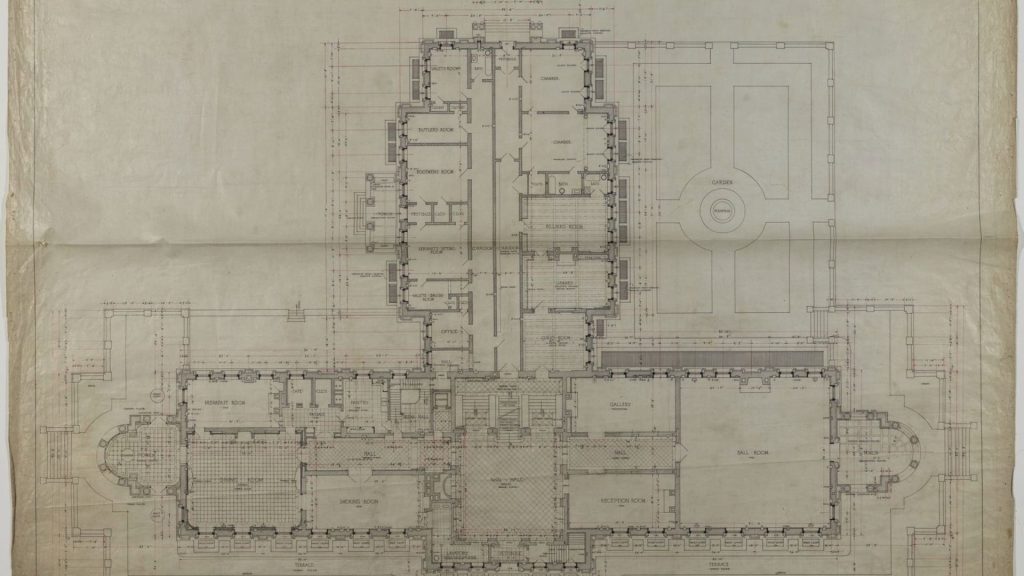

They Don’t Make ‘Em Like They Used To

Horace Trumbauer was known for using the best construction materials and techniques on the manors and mansions he designed. The neoclassical revival styled Lynnewood Hall was built with a structural framework of steel I-beams. The exterior was clad in Indiana limestone with accents of brick, marble, and concrete.

Sparing no expenses, Trumbauer acquired the finest materials from the far corners of the earth for the 110-room Lynnewood Hall. Many of these items are no longer available, making it a challenge for restoration efforts.

Art and Tragedy

With his showy mansion complete, Peter A. B. Widener turned his attention to filling the walls of his new home with art. Widener was an art lover and invested heavily in his personal art collection. He owned at least a dozen Rembrandt paintings, art by Raphael, El Greco, and Donatello, and a few works by new artists, Manet and Renoir, that he acquired on trips to Europe.

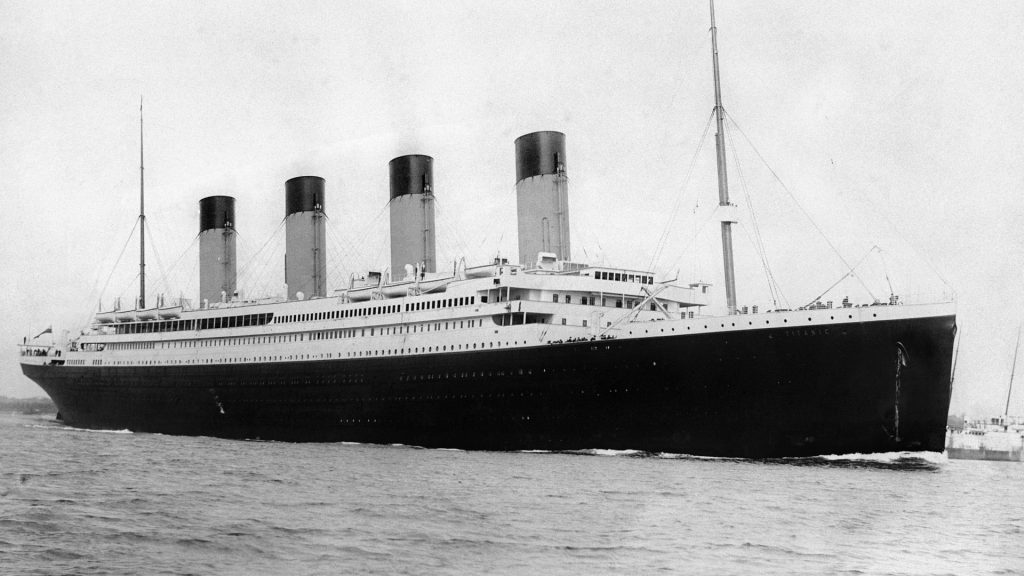

It was on one such art buying trip to Europe that tragedy struck Peter Widener’s family. Rather than traveling himself, he sent his son, George Dunton Widener, in his place. George was accompanied by his wife, Eleanor, and his son, Harry. For their voyage home, the group booked passage on the RMS Titanic, the unsinkable luxury liner that sank on April 14, 1912. The only family member to survive the disaster was Eleanor Widener.

The Last of the American Versailles

Peter A.B. Widener never recovered from the deaths of his son and grandson on the Titanic. His health rapidly declined, and he died on November 6, 1915. His only surviving son, Joseph, took over as the executor of Lynnewood Hall. Thanks to his prudent management, the estate weathered the Great Depression, but the once-stately manor had lost much of its luster.

Joseph Widener’s son, Peter II, recognized that this was also happening to many of the other opulent estates built as ostentatious showpieces built for wealthy businessmen during the Gilded Age. In his 1940 book, Without Drums, he wrote, “The days of America’s privately-owned treasure houses are over… Lynnewood Hall can, I suppose, be called the last of the American Versailles.”

Down, But Not Out

The decline of Lynnewood Hall became even more pronounced after the death of Joseph Widener in 1943. During World War II, the U.S. military used the grounds of Lynnewood Hall to train dogs.

In 1952, a seminary purchased the home and used it as a school and meeting facility, however the seminary sold off many of the interior architectural features, like the fireplace mantels and hardwood paneling, to fill their coffers.

Gutted

In the 1990s, Lynnewood Hall unfortunately sat vacant and nearly gutted.

Journey Ahead

But Horace Trumbauer built the estate to have good, strong bones. Lynnewood Hall may have been down, but it wasn’t out. Not yet at least. In 2003, it was added to the list of the most endangered historic places in the Greater Philadelphia area.

Ownership passed to a newly formed nonprofit group in 2023, the Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation, which is committed to returning the home to its former glory.

Welcoming Guests Once Again

The Lynnewood Hall Preservation Foundation agrees that the former home of Peter A.B. Widener is a masterpiece of American architecture worthy of restoration. Their goal is to restore the building and surrounding groups so that the public can also enjoy the space and marvel at the elegance of the past.

The Foundation has a three-phase plan. The first step is to address structural and mechanical issues with the aging building and to restore the grounds. Step two involves the installation of vast gardens that will replicate the original landscaping, but with a focus on sustainability. The final step will be the complete restoration of the interior, including furniture and art.

Focusing on the Future

When Horace Trumbauer designed and built Lynnewood Hall in 1899, he did so with an eye to the future. He intended the home to serve the Widener family for generations. He couldn’t know, of course, that Peter A.B. Widener only lived in the home for 15 years.

Today, Lynnewood Hall stands as a testament not only to Trumbauer’s talents as an architect, but to the prosperity of the Gilded Age and the desire of many of America’s giants of industry to create lasting reminders of their fortune and success. As Peter Widener II noted in his book, most of the grand manors and estates of the Gilded Age are “gone with the wind.” The few that remain, like Lynnewood Hall, should be treasured.