A new discovery in eastern Germany is suggesting that modern humans (or ‘Homo sapiens’) started migrating beyond the Alps and into northern Europe around 45,000 years ago – more than 5,000 years earlier than previously assumed. This changes everything we thought we knew about the dispersion of Homo sapiens – and the sudden disappearance of Neanderthals not long after.

Initial Excavations Take Place In The 1930s

We’ll get to the new discovery in a moment, but the story really begins more than 90 years ago at a cave site in the eastern German town of Ranis. A team of archeologists spent several years excavating the 8-meter-deep cave in the 1930s, and found unique, leaf-shaped stone tools – which they named LRJ tools.

They didn’t know who made the tools, but they assumed it was the Neanderthals because Homo sapiens didn’t enter northern Europe until several thousand years later – at least, that’s what we thought. Now, a new discovery is challenging that thought, and it could change the fabric of human history.

Excavators Re-Examine The Cave Site 90 Years Later

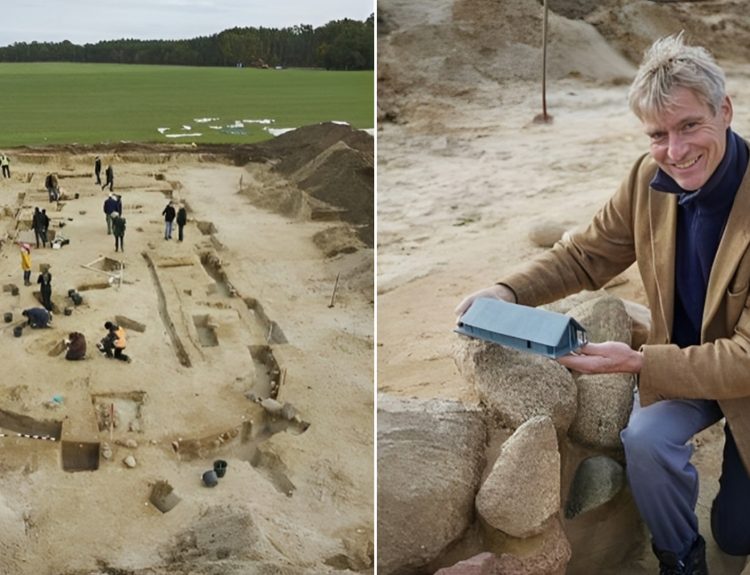

In an effort to learn more about the LRJ tools found at the Ilsenhohle cave, excavators decided to re-examine the pit a second time. They spent six years (2016-2022) inside the cave, using better tools and more advanced technology than what was available 90 years ago.

“The challenge was to excavate the full 8-meter sequence from top to bottom, hoping that some deposits were left from the 1930s excavation,” said Marcel Weiss, one of the co-authors of the new study. Another author added that they had to ‘board up the walls to protect the excavators’

Excavators Find More LRJ Tools Behind A Massive Rock

One of the biggest issues excavators faced in the 1930s was not being able to move a six-foot rock that stood in their way. Luckily, it didn’t prove to be a problem for the modern-day team – in fact, they removed the rock by hand. What they found changed human history as we know it.

First, they found the same LRJ tools that the previous team found. The tools were also found in various other sites around the world, and are named ‘Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician’ (LJR) tools to honor the various origins of the tool – Ranis (Germany), Lincombe Hill (England), and Ojcow (Poland).

They Also Found Thousands Of Bone Fragments

The tools were almost expected, but what they found next was what excavators were hoping to find in the 1930s – bone fragments. And they found thousands of them! At long last, they finally had what they needed to identify who these tools belonged to – Neanderthals, Homo sapiens, or another human subspecies.

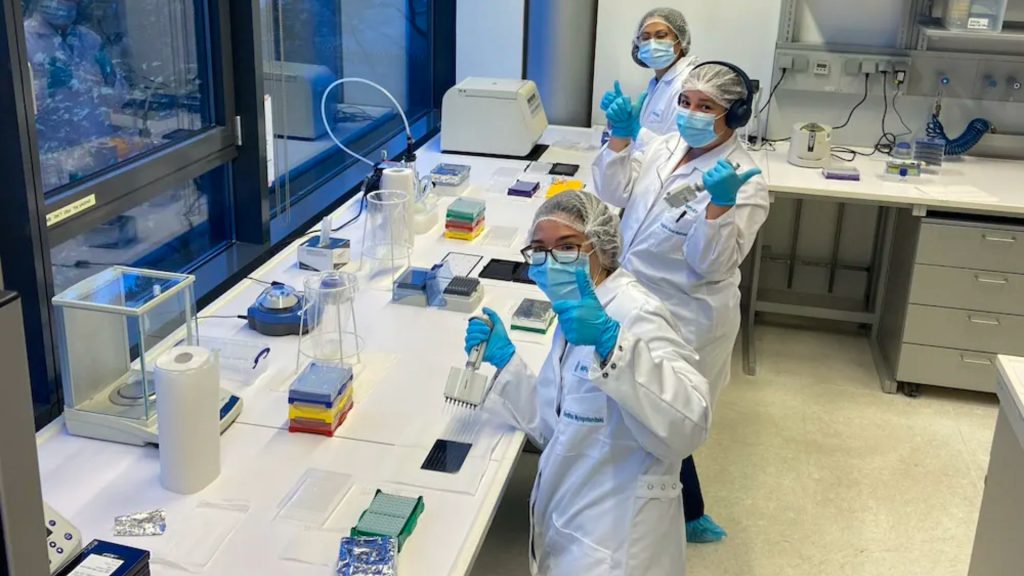

Using paleo proteomics, the researchers separated the human bone fragments from the animal bone fragments. They then used radiocarbon dating and DNA analysis to determine whether the fragments were from the remains of a Neanderthal or Homo sapien. It turns out modern humans were more widespread than originally thought.

Bone Fragments Identified As Homo Sapien

The bone fragments they found behind the rock were the skeletal remains of 13 Homo sapiens. Researchers were shocked – modern humans weren’t supposed to be this far north for another several thousand years. Yet, here they were, mingling with Neanderthals and overcoming harsh climates roughly 47,500 years ago.

“This came as a huge surprise, as no human fossils were known from the LRJ before, and was a reward for the hard work at the site,” said Marcel Weiss – another co-author of the study. The real question is – what were Neanderthals and Homo sapiens doing for 5,000-7,000 years?

Here’s What We Know About The Time Period

The cave site where the bone fragments were found is in eastern Germany, but let’s not forget – this was 45,000+ years ago. The climate back then was much colder than it is today, resembling that of modern-day Siberia or Scandinavia – and they didn’t have heaters back then.

According to the researchers, these particular Homo sapiens lived in small groups that traveled often. They never spent a lot of time inside the cave, but would use it as a hideout for eating the food they caught – such as reindeer, woolly rhinoceros, and horses. They also shared the cave with hibernating bears and denning hyenas.

Were Homo Sapiens More Adaptable Than We Thought?

It is believed that Homo sapiens began migrating out of Africa – where we originated – around 50,000 to 60,000 years ago. It would’ve taken time for them to evolve and adapt to the colder temperatures as they moved into northern Europe, which they thought happened around 40,000 years ago.

Now that we know Homo sapiens moved into northeastern Europe more than 45,000 years ago, many researchers are shocked at how far they came in such little time. “This shows that even these earlier groups of Homo sapiens dispersing across Eurasia already had some capacity to adapt to such harsh climatic conditions,” said one of the co-authors.

What Happened To The Neanderthals?

Homo Sapiens and Neanderthals crossed paths in northern Europe sooner than we originally thought, meaning there’s a good chance they lived alongside one another for thousands of years before Neanderthals died out. Of course, this leads many people to believe Homo sapiens had something to do with their disappearance.

As of right now, we don’t have a definitive answer on how the Neanderthals went extinct, but several theories exist – including disease, violence, and interbreeding. Most people are leaning towards the latter, especially since most of us have a very small percentage of Neanderthal DNA.

Can We Do The Same At Other Excavation Sites?

While we learned a lot about the history of the human race, we also learned a lot about how far technology has come in the 90 years since the cave was last excavated. It makes you think about what else we could find if we were to re-examine other excavation sites that haven’t been touched in decades.

“The Ranis cave site provides evidence for the first dispersal of Homo sapiens across the higher latitudes of Europe. It turns out that stone artifacts that were thought to be produced by Neanderthals were, in fact, part of the early Homo sapiens toolkit,” said Jean-Jacques Hublin (one of the study’s co-authors)