The North Arabian Desert, more commonly called the Syrian Desert, is like most of the world’s deserts – hot, dry, and sparsely populated. Traversing such terrains is difficult today, but it was even more so four thousand years ago. Water is the most precious resource in such an inhospitable place as this.

The nomadic Bedouin people have made their homes in the Syrian Desert for thousands of years, establishing trade routes across the desert, using the natural oases as stopping points where they could replenish their precious water supply. A recent archaeological discovery at one of these oases shows us that the water was protected by a defensive fortification as long ago as the Bronze Age.

The Syrian Desert

We can tell by the various names of this desert that many of the nations it touches want to claim it as their own. This expanse of open, dry, gravelly land goes by several names, including the Syrian Desert, the North Arabian Desert and the Jordanian Steppe.

The desert covers part of southern Syria, western Iraq, eastern Jordan, and northern Saudi Arabia. In fact, the North Arabian Desert merges into the Arabian Desert. In all, this desert stretches across 200,000 square miles.

A Miracle of the Desert

Desert oases are welcome sights in the dry, arid deserts. Unlike the inhospitable and dangerous landscape surrounding it, an oasis is typically lush, green, and full of life. That is all thanks to a steady supply of water, usually from a natural spring, well, or an underground aquifer.

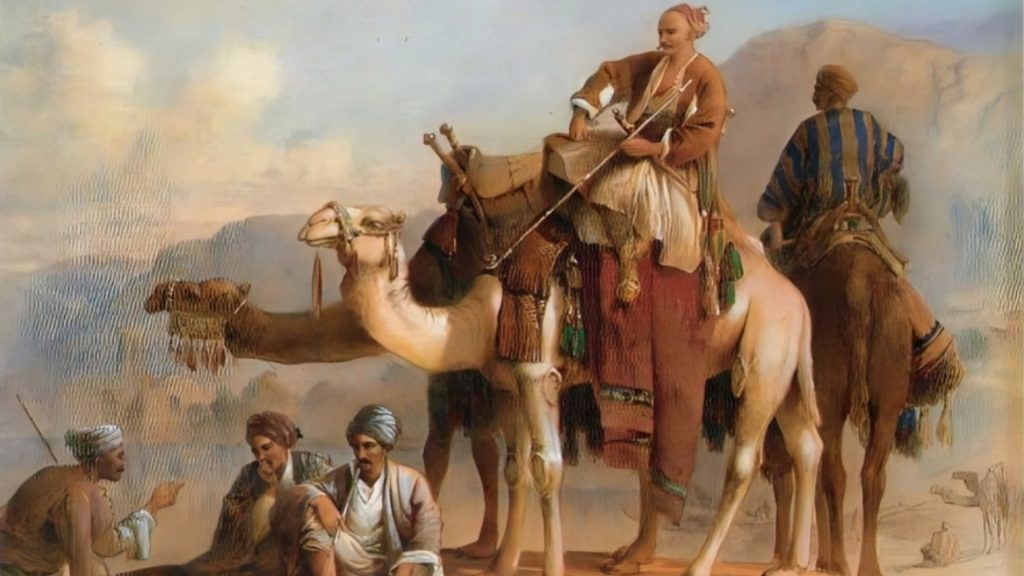

Without oases, there would be no trade routes across desert regions, like those in the Middle East and Africa. These miracles of the desert supply life-sustaining water for humans and the domesticated animals that were used to carry or pull trade goods.

Ancient Settlements in the North Arabian Desert

Bedouin tribes crisscrossed the desert, and, in time, permanent settlements were established at key oases in the North Arabian Desert. One of the largest and most important of these settlements is Palmyra.

Strategically located along the Silk Road, Palmyra served as a trading outpost between communities in the far east and those along the Mediterranean Sea. Palmyra dates back to 2000 BC and was mentioned frequently during Roman times. It prospered by levying taxes on caravans passing through the city.

The Oasis of Khaybar

Located less than 100 miles north of the Saudi Arabian city of Medina, the Khaybar oasis has a long and interesting history. Long the home of Arabian Jewish tribes, it faced turmoil after the introduction of Islam in the 7th century.

The Jewish population was ousted from Khaybar in the year 567 AD when King Al-Harith ibn Jabalah and his army of Arab Christians invaded. Later, during the Battle of Khaybar in the year 628 AD, Muhammad and his Muslim army captured the oasis.

Khaybar Through the 7th Century

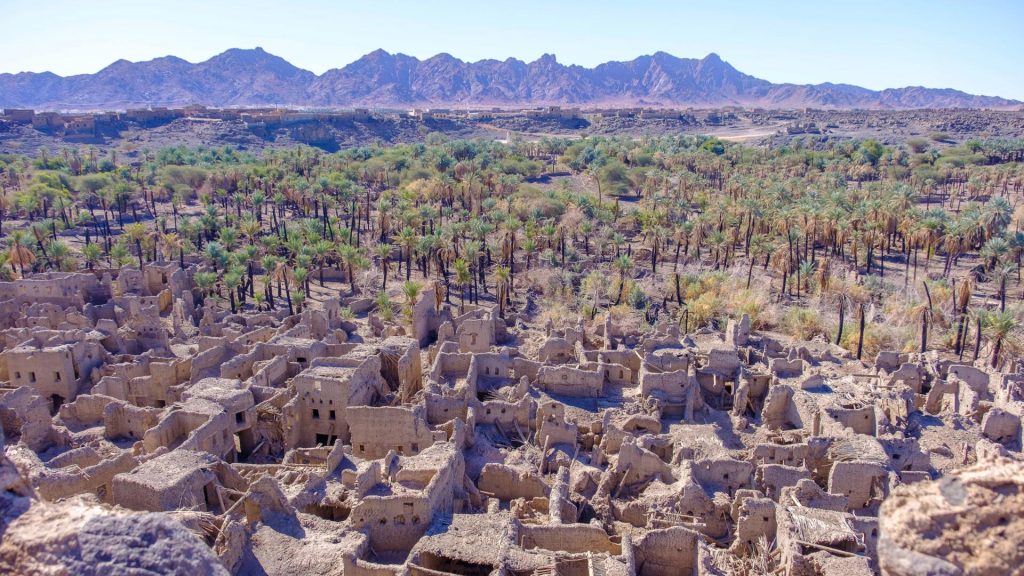

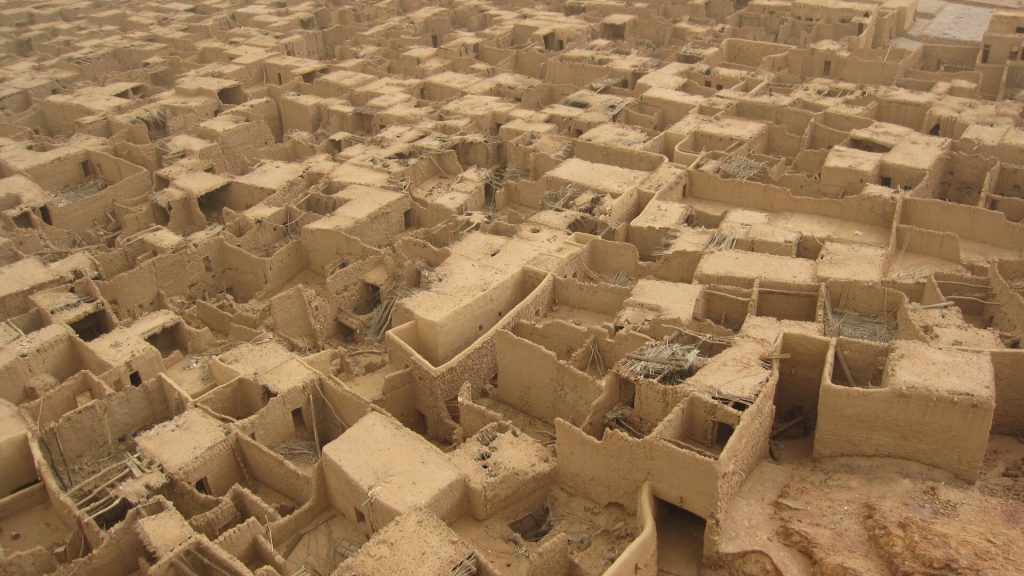

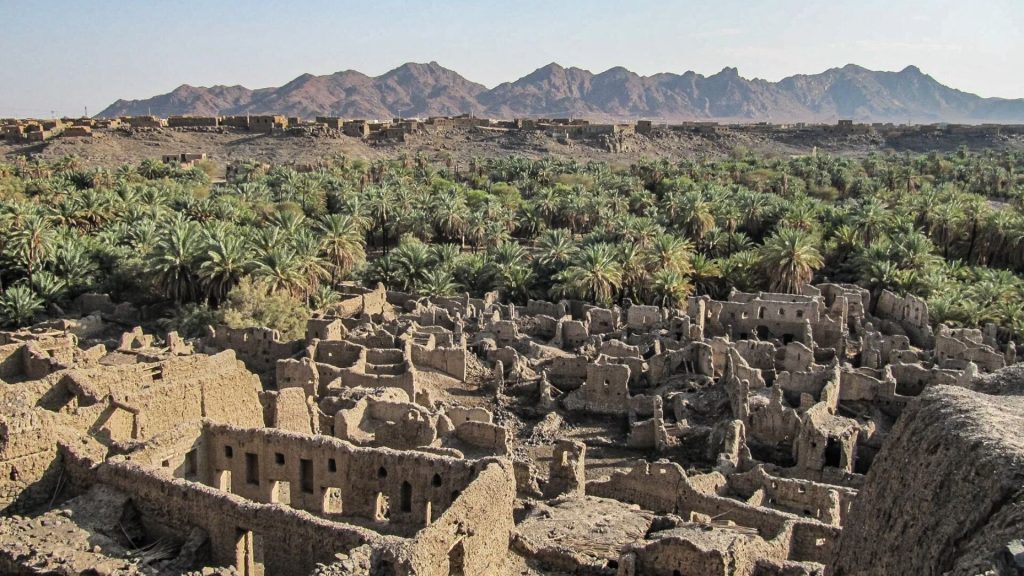

King Al-Harith ibn Jabalah eventually released his Jewish prisoners who returned to Khaybar. They are credited with growing date palm trees and engaging with trade. Each of the oasis’s three sections – separated by natural features such as swamps – had several fortresses.

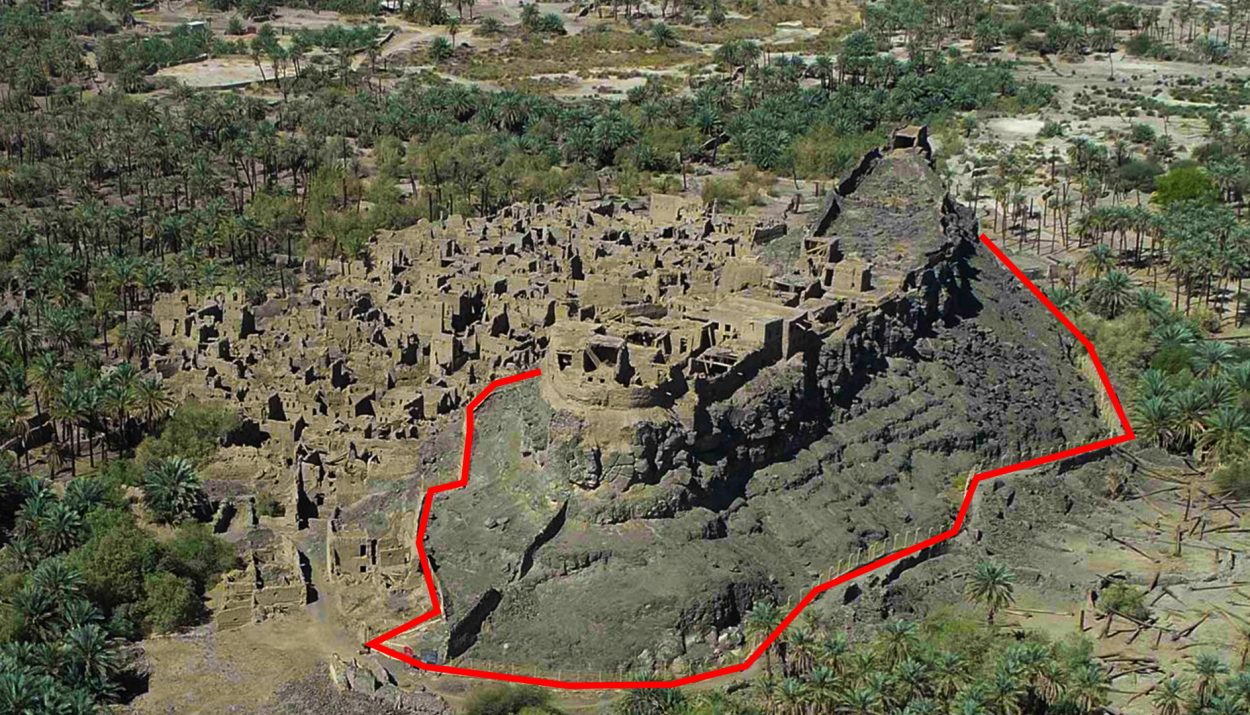

Multiple families occupied each of the fortresses. In addition to homes, the fortresses had stables, workshops, and storage rooms. The fortresses were notably constructed on higher points of land, either hills or rocky outcroppings to provide a defensive vantage point. A recent find proves that this wasn’t the only defensive structure in Khaybar.

A Recent Archaeological Discovery

Archaeologists from the French National Center for Scientific Research and the Royal Commission for AlUla have made a recent – and remarkable – discovery at Khaybar. The research team used historical research, remote sonar imagining, and field study in their work.

What their study revealed was that during the Bronze Age, roughly between 2250 and 1950 BC, the entire oasis of Khaybar was surrounded by a fortification wall. While not all of the wall is still standing, the archaeologists have been able to identify where it once stood.

What Is a Rampart?

The wall surrounding the oasis could best be described as a rampart. Commonly found around castles or walled cities, ramparts are not typical stone walls. Instead, ramparts are wide enough to have a walkway along the top.

Periodically along the ramparts, parapets or lookouts can be found. Guards can walk along the top of the wall, moving from parapet to parapet, to scan the surroundings for enemy invaders.

A Lengthy Wall

The remaining portion of the rampart when added to the footprint of the fallen part of the wall adds up to a nine-mile-long wall that completely circles the oasis. That makes the rampart at Khaybar the second longest one in Saudi Arabia.

According to the researchers, the rampart wall at Khaybar’s oasis enclosed an area of about 2,700 acres. The city of Tayma has the only known rampart that is longer than the newly discovered one. The Tayma wall is about twelve miles long.

Calculating the Dimensions of the Wall

According to the archaeological team, finding the Khaybar wall “constituted a significant scientific challenge.” The sonar imaging helped the researchers calculate the original dimensions of the wall.

They determined that the rampart wall varied between 5.6 and 7.9 feet thick and had a maximum height of 16 feet. Unfortunately, the researchers explain that less than half of the original wall can still be seen today.

What Happened to the Original Wall?

The rampart that remains at Khaybar can be found with one of the large fortresses built during the Islamic period. From this, it is hard to imagine that the wall surrounded the entire oasis. There is no indication that the wall was as long as it was.

According to the research team, the desert environment has changed over the last four thousand years. Shifting desert sand erased portions of the wall. Other parts may have been dismantled as the city grew and expanded. Because of this, the wall went undetected for thousands of years.

Walled Oases Were Not Uncommon

The archaeologists explain that at the time when the rampart at Khaybar was built, it was common for fortified structures to be erected at the desert oases in the North Arabian Desert. In fact, they believe that Khaybar was one of a network of other walled settlements across the desolate desert.

Numerous other walled oases have been documented in the North Arabian Desert, all dated to the Bronze Age. The presence of the fortification shows that these areas had permanent settlements as long ago as the fourth millennia BC.

Why Was the Wall Built?

According to Guillaume Charloux, an archaeologist with the French National Center for Scientific Research, “The purpose was probably mainly protective” and as a way to separate the agriculture regions from residential areas.

Charloux continued, “Protection was not operated by an army, but it was a passive defense.” If this is the case, it makes researchers wonder about the people who built the wall.

Khaybar’s Past Offers a Clue

As we now know, Khaybar had a violent past. The Arab Christians and Arab Muslims both tried to eradicate the Jewish population during the 6th and 7th centuries. In all likelihood, these invasions had as much to do with geography as they did with religious strife. The Khaybar oasis offered travelers and traders a vital stop along the desert trade routes.

The water and agricultural products grown at the oasis helped resupply trade caravans. The people of Khaybar charged a tax on these caravans and, naturally, charged a high price for access to the water and added a hefty price tag to the other supplies. If another group could control the oasis, they, too, could profit from its natural resources.

An Old Wall, But Not That Old

The rampart wall encircling the oasis of Khaybar is quite old. It has been dated to be as much as 4,000 years old. But when compared to other similar structures in the world, it’s not that old.

The oldest walled oasis that archaeologists have unearthed is an eye-popping 8,000 years old. This is a Stone Age fort in Amnya in Siberia’s Lower Ob area.

Shining a Light on Desert Life

As Charloux explained, now that the researchers have identified Khaybar as one of several walled oases in the North Arabian Desert, it expands on the current understanding of how humans used these verdant oases in the Bronze Age.

He noted that the find “furthered our understanding of the social complexity of the pre-Islamic period.” The discovery adds another chapter to the story of human occupation of this inhospitable region.

Further Study of the Area

The team’s report, which was published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, concluded, “In addition to the discovery of a unique and securely dated monument, the recognition of the Khaybar walled oasis constitutes a crucial landmark in the architectural and social heritage of north Arabia.”

While this discovery reinforces the fact that freshwater sites aided Bronze Age trade, it also tells us how representatives of some of the world’s major religions sought to control strategic locations from the Bronze Age through the Middle Ages.