Roman mariners were famed for sailing all over the Mediterranean, controlling the region, and dominating the seaways for Rome. But what if there was evidence that the Romans made it to the New World a whole millennium before Columbus? This remarkable discovery might prove just that. Let’s examine what it is and what it can tell us about the past.

Roman Sailing Ships Dominated the Mediterranean

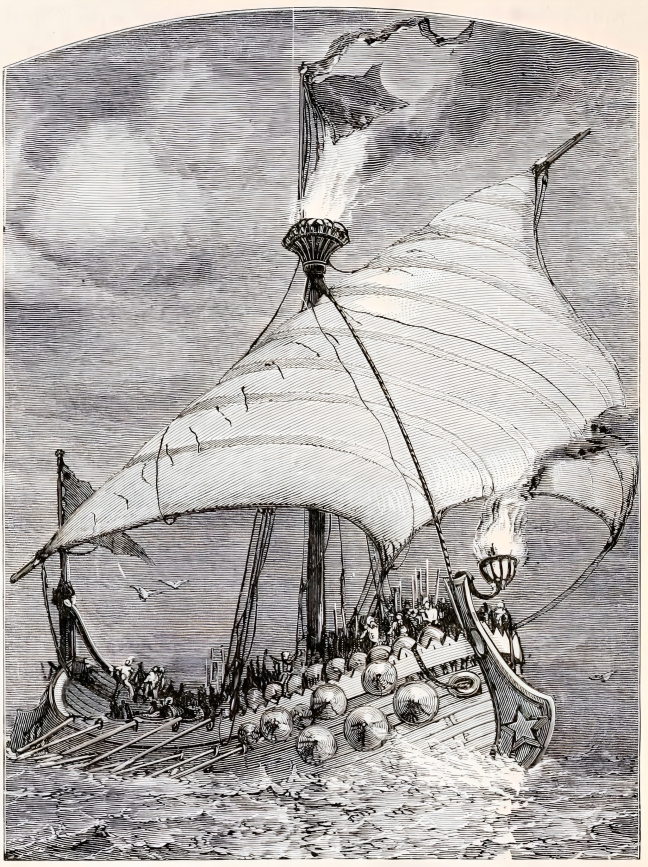

Romans were well-known across the Mediterranean for their naval prowess and innovative approach to sailing. Leveraging their exceptional engineering skills, they constructed advanced warships like the quinquereme, boasting superior maneuverability and strength. The Romans adeptly adapted the “Corvus,” a boarding bridge, enabling them to board and conquer enemy vessels swiftly.

With an organized fleet and disciplined sailors, they controlled crucial trade routes, enabling efficient transportation of troops and resources. This dominance granted them military might and economic influence, consolidating Rome’s position as a formidable maritime power in the Mediterranean, crucial to their expansion and dominance in the ancient world.

Sailing Across the Atlantic?

Most people think that civilizations like Rome and Ancient Greece couldn’t possibly make their way across the Atlantic. Despite the massive distances involved, it was actually possible that they could make their way to the New World. The sailors of the Roman Navy weren’t clumsy, uneducated people but were well-trained in their craft.

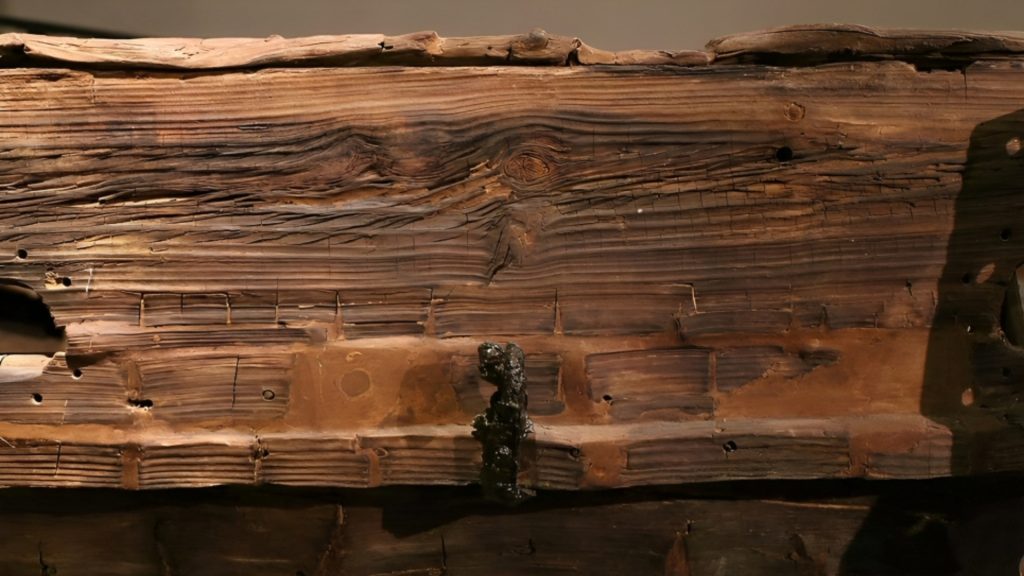

The boats were also very well-constructed. Roman boat construction showcased remarkable engineering, employing sturdy oak for hulls and intricate joinery. They could stand up to almost anything the Mediterranean could throw at them. However, the distance to the New World would be a huge undertaking.

What Makes Us Think They Got There?

In the 1970s, a researcher named Thor Heyerdahl sailed a reed boat across from Africa to the shores of the New World. He made this undertaking with shipbuilding skills and navigation tools standard in the ancient world. It showed what it would take to make it from one side of the Atlantic to the other.

While it was certain that the Romans didn’t think the earth was flat (despite many people thinking they did), they probably didn’t set off to discover the New World. However, scientists have found evidence that the Romans might have made it here.

Evidence Of Roman Landings on Oak Island

In 2015, J. Hutton Pulitzer, the head of the Ancient Artifact Preservation Society, and his colleagues announced the discovery of a Roman ceremonial sword. According to reports, the sword was initially discovered many years ago as it was hauled onto a fishing boat along with the catch.

It was only in 2015 that the sword was passed on to researchers. The original finder had long since passed away. Still, the sword’s presence in the waters around Oak Island adds to the mysterious blend of occurrences and discoveries that happen in the area. The island has been a hotspot for debate since the 18th century.

Oak Island – An Overview

Oak Island itself is a bit of an enigma. Over the years, several stories have circulated about treasure, strange happenings, and curses that litter the tiny island in Nova Scotia. Excavations into the area have discovered a weird cache of treasures, including flagstones, irregular markings, and assortments of booby traps.

Since the 1790s to now, the island has been shrouded in mystery. Many researchers mention evidence of a shipwreck in the lagoon, along with odd, out-of-place artifacts pointing to something that’s unexpected or supernatural. The island has been the subject of a show from The History Channel exploring its mysteries more in-depth.

What Evidence Is There For a Roman Shipwreck?

The most compelling evidence researchers have is, of course, the Roman ceremonial sword that would probably have belonged to someone influential on the journey. XRF testing on the sword showed that it contained the materials for a sword that would have existed during that time. But the sword is only one piece of evidence.

Other evidence in the area includes petroglyphs carved by a local tribe, which may show a Roman procession. Gold Roman coins were also found on the mainland near Oak Island. In 1901, a Roman legionnaire’s whistle was found buried in the mud on the island. While this evidence is circumstantial, it points towards a solid conclusion.

DNA Evidence Is Also Present

The natives of the area were part of the Mi’kmaq people. Many of the descendants of those people exist today, and their DNA has been tested. Usually, in these tests, one would expect to find the typical DNA markers for North American tribes, but inside the DNA molecule was something unexpected.

The DNA tests on these descendants showed a remnant that was present, unlike anything North American tribes would have. When traced back, this remnant seemed to stem from the Eastern Mediterranean region, suggesting that the DNA had mixed with someone from that area long ago.

European Barberry Suggests More Roman Presence

Berberis vulgaris, or European barberry, is not a native species to North America. It was, however, extremely common in the Eastern Mediterranean region where the Romans came from. The plant provides a tart berry that can be used as a snack or added to food for seasoning.

Despite this herb not being native to the region, Oak Island has a significant population of European barberry, suggesting that someone brought a sample of the plant across hundreds of years ago. Historical records show that Roman soldiers used the plant to prevent scurvy because of its high vitamin C content.

Testing the Sword

The sword was tested using X-ray fluorescence (XRF), which involved bombarding it with X-rays to excite the molecules making it. Researchers could use this method to determine which metals were present in the sword. They deduced that platinum, silver, gold arsenic, tin, lead, copper, and zinc were in it, consistent with other swords from the Roman Empire period.

What’s more, the sword features a familiar construction on the hilt. The sword’s depiction of Hercules on the hilt suggests that it’s a ceremonial sword given to outstanding gladiators and warriors of the Empire. Whoever owned it was pretty important.

Why Did It Take So Long To Find the Sword?

According to the researchers, the original finding of the sword happened around the 1940s, but it was kept secret. The secret was partially because the finder didn’t know what they had in their possession. But it was also because of how they found it.

Researchers only got the sword in 2015 because the finder was doing some illegal scalloping in the waters around Oak Island in the 40s. The rake they were using brought the sword up easily, but they simply took it and hid it away since it was damning evidence of their illegal activity.

Some Questions About The Sword

As mentioned, the sword was used on the reality show “The Curse of Oak Island,” where the crew took the blade to be tested at a local university. They were convinced that they could get the university to corroborate their thoughts that the sword was ancient in origin.

Unfortunately, the crew got something they didn’t bargain for. St. Mary’s University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, used a sliver of the sword for testing and returned with a result saying that the sword’s metal contained a high zinc content, suggesting that it was modern brass, not from an ancient source.

Why The Discrepancy?

Obviously, the outcome was not what the researchers had expected or wanted. Yet they also had some problems with the tests. The crew claimed that the tests on the sample might be flawed because it only took a surface-level sample of the sword for testing.

As the XRF testing delved deeper into the construction and metallurgy of the sword, the crew was more inclined to believe that the sword was of ancient make and not from modern metal production. More testing would be necessary to confirm or deny these results.

Can’t They Use Carbon-14 To Date the Sword?

Unfortunately, Carbon-14 (C14) dating only works with organic tissues and wouldn’t have any impact on trying to date when the sword was forged. C14 uses radioactive isotopes absorbed by organic material to determine the date of a sample. Metal doesn’t absorb C14 atoms.

As a result, researchers are left trying to piece together the timeline of the sword based on the metals used to make it, the designs on the hilt and haft, and any other identifying marks or carvings on it. The metals tell a story of their own.

Similar Swords In Europe

One of the primary researchers thinks the bronze in the sword they found may come from a mine in Breinigerberg, Germany. His conclusions are based on a finding of two swords with similar construction in an ancient settlement near this area.

The team claims that the bronze found in this area is typically high in zinc content, suggesting why the chemical test showed such a high metal concentration. The lead researcher suggested that the sword’s material is better classed as bronze since the zinc is naturally occurring and wasn’t added afterward, like in modern brass production.

Time to Change the History Books?

The generally accepted wisdom is that Columbus rediscovered the Americas in the 1400s. Yet this new evidence suggests that Roman ships made it here as much as a thousand years before the three ships of the Genoan even left port in Madrid.

While this suggestion will need a bit more research, there is a lot of circumstantial evidence that needs to be revised before scholars and experts will accept it. We may have to wait a while before we can say for sure the Romans got to the New World first.