Between 1823 and 1865, a group of 70 enslaved African Americans were ordered to construct a private Jesuit university in St. Louis, Missouri. It is an unfortunate reality that slavery was legal in parts of the United States during this time.

Now, as much as two hundred years later, descendants of those slaves are seeking reparations from that private Jesuit university, St. Louis University. Reparations are nothing new, however the amount of reparation money in this case greatly exceeds the university’s total endowment. Let’s take a closer look at the founding and construction of St. Louis University.

Slavery in America

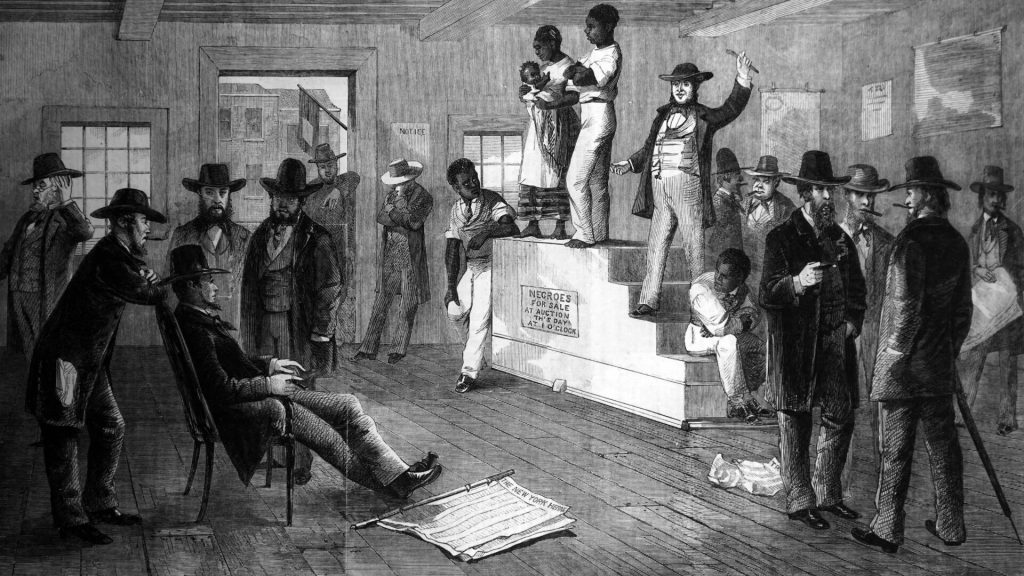

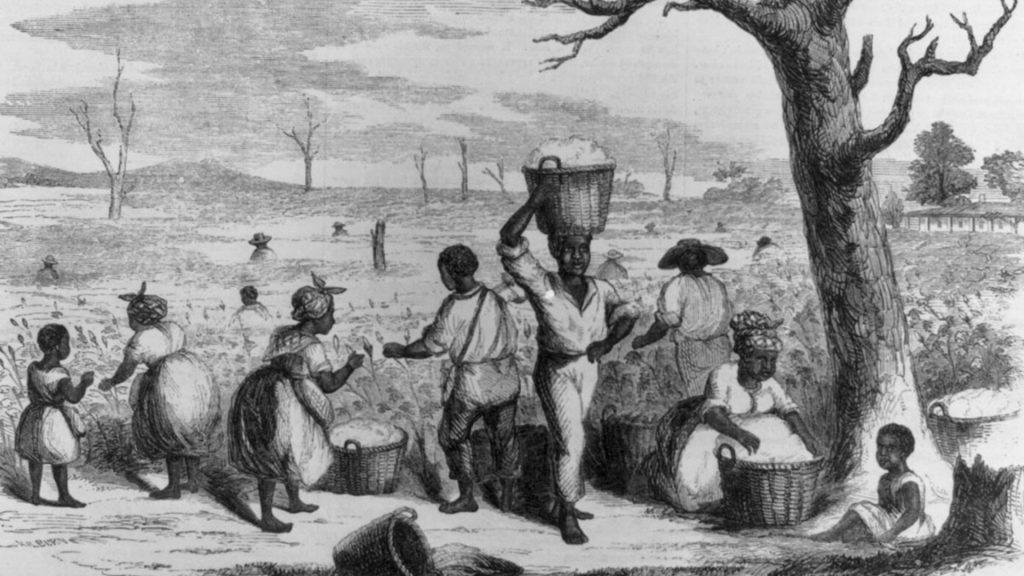

Slavery represents a dark chapter in American history. Long before the United States declared its independence from England, the first African slaves arrived in the New World. Slaves were used on the vast cotton and tobacco plantations of the South. These were labor-intensive crops that were vital to the economic growth of the new county.

During the westward expansion, the issue of slavery was hotly debated. Missouri was in the crossfire of these divisive views. Two acts of legislation – the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and of 1850 – sought to keep the number of free states and slave states equal, but these attempts only fanned the fires until the conflict hit its boiling point.

Slavery and the American Civil War

Although slavery wasn’t the only factor that sparked the American Civil War, it was certainly one of the biggest. The morality of enslaving other human beings and forcing them to do unpaid labor was balanced against the economic value of a readily available, free workforce.

The American Civil War pitted the anti-slavery industrial North against the pro-slavery, agrarian South. The brutal and violent war, which lasted from 1861 to 1865, culminated in the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, which freed all the slaves in the Confederate states, as well as the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution in 1865 which ended the institution of slavery in the U.S.

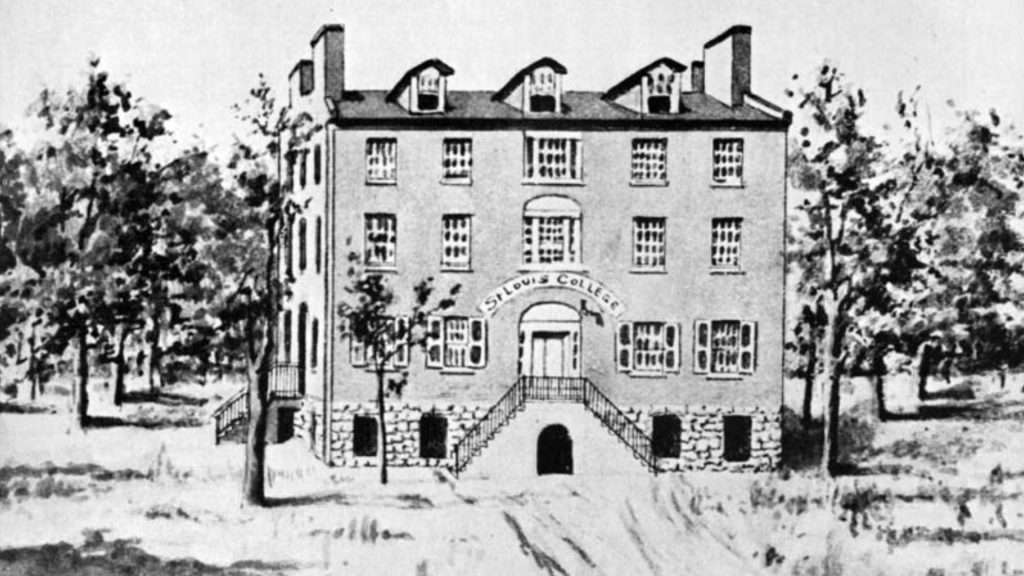

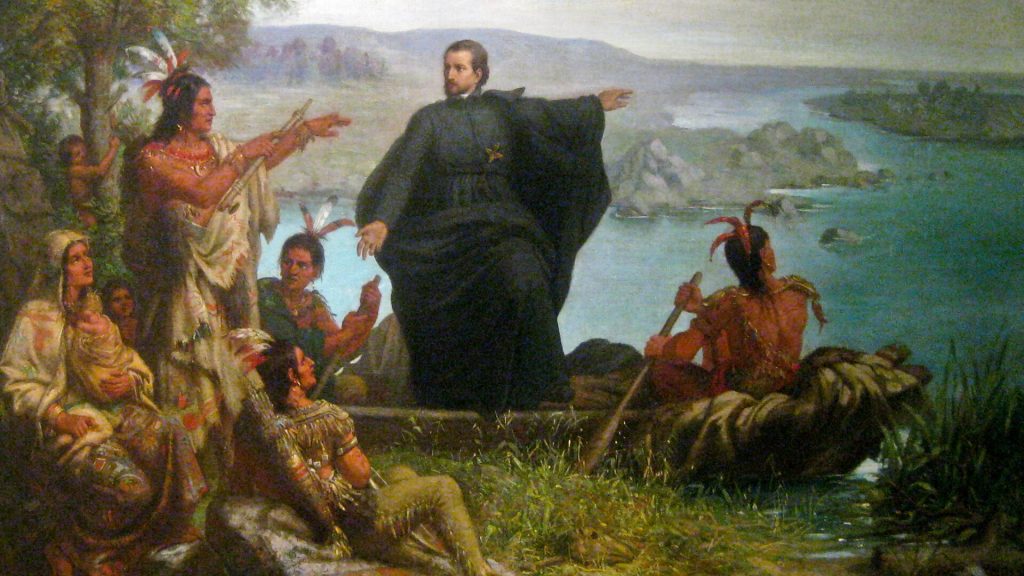

St. Louis University, a Jesuit Research University

Headquartered in St. Louis, Missouri, St. Louis University is the second-oldest Jesuit college in the country and the oldest university located west of the Mississippi River. The educational institution was founded by Louis William Valentine DuBourg, the Bishop of Louisiana and the Floridas, in 1818.

Not long after the school was established, Bishop Dubourg appointed the Jesuits of the Society of Jesus to lead the college. At that time, it was called St. Louis College. It was still called St. Louis College when it applied for and received its official charter from the Missouri legislature as a university.

The Jesuits and Slavery

In the early days of the United States, most Catholic orders located in areas where slavery was legal owned enslaved African Americans. The Jesuits, however, owned many more slaves than other religious groups. It all stems back to the Jesuits’ early arrival in the New World.

When the Jesuits arrived in Maryland in 1643, they were granted a sizable tract of land for a plantation. This became their primary source of income for more than a century and a half. But it was a lot of work. They needed help so they turned to African American slaves. The first documented record of slave owning by the Jesuits dates to 1717.

Moving and Expanding the College

In 1829, after St. Louis College became St. Louis University, the Jesuits relocated the school’s campus and expanded its size. To build the new university campus, the Jesuits brought in a work crew of enslaved African Americans from a nearby theology school they ran, St. Stanislaus Seminary.

The slaves at St. Stanislaus Seminary in Hazelwood, Missouri, had been brought there from the Jesuit’s main plantation in Maryland. In doing so, the Jesuits broke one of their unwritten rules … they separated spouses from each other and broke apart family units.

Two Waves of Relocated Slaves

The first group of enslaved African Americans that the Jesuits brought to Missouri in 1823 included three married couples. They were Moses and Nancy Queen, Thomas and Mary Brown, and Isaac and Susan Hawkins. They left behind their children, parents, siblings, and other loved ones.

The Jesuits relied on their slaves to accomplish a number of tasks. When it came to the construction of St. Louis University, the Jesuits needed additional help. In 1829, they transported another 18 African American slaves from their plantation in Maryland to St. Louis some 800 miles away.

Ongoing Work on the Campus of St. Louis University

For 42 years, the Jesuits kept a work crew of enslaved African American engaged in ongoing work on the campus of St. Louis University. The slaves constructed buildings, dug wells, built roads and walkways, and cleared trees.

As the Jesuits’ records show, 70 slaves in total were forced to build St. Louis University. Work was ongoing until 1865 – a significant year. The Civil War ended in 1865, but this was also the year that slavery was abolished with the passage of the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Fast Forward to 2024

When we fast forward to the present day, we find that St. Louis University is a thriving, vibrant place of learning. It boasts an enrollment of about 8,500 undergraduate students and roughly 6,700 graduate students. The university offers 94 majors for undergraduates and 88 graduate degree majors.

A high-level doctoral research facility, St. Louis University faculty and students work on science, technology, and humanities research projects. SLU’s athletic teams compete in the Atlantic 10 Conference. And, St. Louis University has been forced to face its slavery past.

Seeking Reparations

Working with social justice advocates, a group of people who are descendants of the slaves owned by the Jesuits who were forced to build St. Louis University have demanded reparations from the university. The amount the group is requesting is staggering – $74 billion! For reference, SLU has an annual endowment of only $1.5 billion.

According to economist Julianne Malveaux, the $74 billion amount was determined by using standard calculations and was based on the unpaid labor of 70 slaves. She explained, “The calculations that we came up with and the methods that we used are time-honored methods.”

Reparations: An Attempt to Undo Past Wrongs

“Reparations” is a buzzword we have been hearing in recent years. It is the belief that descendants of enslaved people deserve acknowledgement and financial compensation because their ancestors suffered from oppression and racial discrimination. The goal of reparations is to repair the wrongs of the past and to attempt to undo the long-term impacts that slavery had on future generations.

Support is growing among many groups for reparations for the descendants of enslaved people, however it is a contentious subject. Opponents of reparations question just how a person living today is still suffering from wrongs done to an ancestor who lived six generations ago. It is certainly a complex issue.

Connecting the Past with the Present

Rashonda Alexander is one of the descendants of Jack and Sally Queen, an enslaved couple who were brought to St. Louis in the second wave of the Jesuits’ slave relocation and who worked to build St. Louis University. She is also a 2002 graduate of SLU. However, she only learned of her ancestors’ connection to the school in 2020.

Alexander said, “I attended the university my ancestors built for free. I keep thinking, ‘Did I walk on their blood?’.” Alexander hopes to see the university take responsibility for its past atrocities. She said, “I believe souls can’t rest until fundamental wrongs are done right.”

The Shameful Mark on the Jesuits

At a 2017 event, Father Timothy Kesicki, the president of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States, told the audience, “We have greatly sinned.” For today’s Jesuits, the order’s history of slavery is shameful. Father Kesicki publicly apologized for the Jesuits’ participation in the institution of slavery.

The Jesuits have established the Slavery, History, Memory, and Reconciliation Project, or SHMR. The aim of this project is to acknowledge the past sins of the Jesuit slave owners, recognize the contributions of enslaved people, and to address ways to move forward. But what that means for reparations is not yet clear.

“Overdue, Negligent, and Wrong“

Civil rights attorneys and advocates have presented their reparations request to St. Louis University. As Malveaux remarked, “The university, quite frankly, is overdue, negligent, and wrong.” She added, “We are not asking for a handout. We’re asking for their debt to be paid.”

In response, SLU has issued statements expressing regret for both the Jesuits’ participation in slavery and for the school’s delay in accepting ownership of its own history. The statement did not, however, announce SLU’s commitment to paying the $74 billion in reparations.

Reparations Can Come in May Forms

“Participation in the institution of slavery was a grave sin,” SLU stated. “We acknowledge that progress on our efforts to reconcile with this shameful history has been slow, and we regret the hurt and frustration this has caused.”

In the statement, SLU reaffirmed its commitment to establishing ongoing relationships with the families that are descendants of the slaves forced to build the university and to honor the memories of these individuals. “Continuing this work is a priority for SLU and the Society of Jesus,” the statement said.