The United Kingdom wasn’t always an island. Thousands of years ago, when water levels were lower, a landmass called Doggerland connected the UK with the Netherlands. Now, archaeologists are using modern technology to explore the submerged Doggerland.

The archaeologists, however, are using a type of magnetic imaging technology that has, until now, only been used to image dry land. Even though they are pushing the boundaries of this technology, they are finding success in their study of Doggerland.

What Was Doggerland?

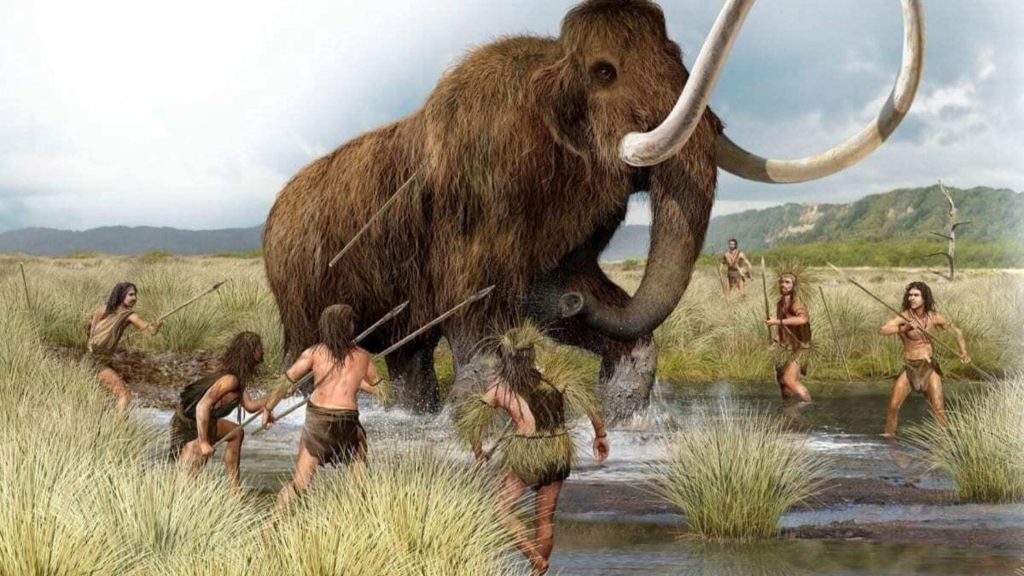

Doggerland was a landmass that once linked Britain to the European continent. It was an extension of the coastlines of Great Britain, the Netherlands, Germany, and the Jutland peninsula. In the Mesolithic period, humans lived across Doggerland where game animals, fish, and plant life were abundant.

Researchers believe that hunter-gatherers migrated to Doggerland in search of a steadier food supply. They certainly know they were there … thousands of ancient artifacts have washed ashore from Doggerland settlements.

What Happened to Doggerland?

Ironically, Doggerland was a refuge for people during the last Ice Age, but it was the end of the Ice Age that spelled doom for Doggerland. The melting ice sheets and glaciers caused sea levels to rise. It was a slow process, but the water rose by nearly six feet every hundred years for a millennium.

Within a thousand years, Doggerland was transformed from a landmass to a collection of low-lying islands. While climate change was the main culprit in the demise of Doggerland, a devastating natural disaster was the final nail in the coffin.

A Norwegian Tsunami

Around 8,200 years ago, an underwater landslide off the Norwegian coast and the resulting tsunami obliterated most of what was left of Doggerland. A University of Bradford archaeology professor Vincent Gaffney explained, “If you were standing on the shoreline on that day, 8,200 years ago, there is no doubt it would have been a bad day for you.”

It may have been the tsunami that sent the remains of Doggerland below the waves of the North Sea, this landmass was already headed in that direction. Gaffney stated, “Ultimately, it was climate change that killed Doggerland.”

Mapping Doggerland with Help from an Unexpected Source

Danish and British archaeologists working on a project to recreate a map of pre-flood Doggerland recently got help from an unexpected source using cutting edge technology. What was that source? Oil drillers!

Oil companies planning drilling operations in the North Sea are required to do a thorough survey of the area. They shared their findings with the archaeological researchers which has aided greatly in the mapping project. In addition, the archaeologists have gathered data in a revolutionary way.

Using Ground-Penetrating Magnetometry

Magnetometry employs ground-penetrating radar to record the magnetic fields in a specific area. The resulting data reveals anomalies that could be significant archaeology sites. Archaeologists have been using magnetometry for a number of years to peer beneath the soil, however the Doggerland researchers got creative with this technology.

The magnetometry survey done at Doggerland was one of the first times that ground-penetrating magnetometry was used for a submerged area. And it worked! The team of archaeologists have been able to identify places of interest.

A Time and Effort-Saving System

With the magnetometry data in hand, the researchers can focus their underwater excavations on potentially significant targets rather than wasting time, effort and money taking a hit-or-miss approach.

The region of the North Sea that was once Doggerland is quite vast. By employing the ground-penetrating magnetometry, the team can make the best use of their time. And, time has become a factor in their research efforts.

A Race Against Time

As part of the British government’s goal to increase wind-generated power and to take a big step toward achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, several energy companies have plans to build off-shore wind farms in the North Sea.

Although these endeavors will help reduce our negative impact on the environment, it will also render large portions of the North Sea inaccessible to archaeological research. Gaffney and his team from the University of Bradford are in a literal race against time.

What Are the Archaeologists Hoping to Find?

According to doctoral student Ben Urmston of the University of Bradford, the research team is pouring over the magnetometry data looking for clues in the magnetic field. He explained, “Small changes in the magnetic field can indicate changes in the landscape, such as peat-forming areas and sediments, or where erosion has occurred, for example, in river channels.”

Armed with this information, the team can identify areas where Doggerland was inhabited. He added, “As the area we are studying used to be above sea level, there’s a small chance this analysis could even reveal evidence for hunter-gatherer activity. That would be the pinnacle.”

Looking for Dumping Grounds

Urmston also noted that he is also keeping an eye out for middens. “We might also discover the presence of middens, which are rubbish dumps that consist of animal bones, mollusk shells, and other biological materials, that can tell us a lot about how people lived.”

Over the years, artifacts from Doggerland have been discovered, including the fossilized remains of deer, hyenas, and mammoths. Bones from a young male Neanderthal have also been found. One find in particular proves that Neanderthals were more intelligent and sophisticated than previously thought.

A Neanderthal Tool

According to Dr. Sasja van der Vaart-Verschoof, the assistant curator of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, one of the most significant finds yielded by Doggerland is a prehistoric tool that dates back about 50,000 years.

The tool used flint held in place using pitch from a birch tree. As Dr. Van der Vaart-Verschoof explained, this tool demonstrates that Neanderthals were “capable of precise and complex multi-staged tasks.” If there are more artifacts such as this yet to be found in Doggerland, the archaeologists hope to make those discoveries … and make them soon.