A completely intact chicken egg, thought to be about 1,700 years old, is believed to be the only one like it in the world after scientists found it still had liquid inside.

It was found during a dig in a site known as Berrysfield in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, Southeast England between 2007 and 2016. Researchers said that it was a one-of-a-kind discovery at the time.

Roman Era Discoveries At Berryfields Site

The site borders the Roman road of Akeman Street and is next to the Roman town of Fleet Marston. Oxford Archaeology, which is set to publish a book on the findings at the Berryfields site, says the discoveries have helped build a better view of life in Roman Fleet Marston and surrounding villages.

During the excavations, archaeologists discovered a large, waterlogged pit or well dating between A.D. 270 and A.D. 300 during Britain’s Roman period. Inside the pit, archaeologists found pottery vessels, coins, timber, leather shoes, animal bones, and a woven basket with a cache of eggs inside it.

Bridge Clues And Roman Economy Insights

It’s thought the timber piles supported a bridge that carried the Roman road of Akeman Street over the River Thame.

Researchers say that the discoveries from the excavation show the importance of livestock, particularly horses, in the Middle Iron Age and Roman economies. They believe it provides insights into the nature of Roman Fleet Marston, previously only known from occasional finds.

Uncovering Ancient Routes

Evidence from Berryfields and other sites in the area shows that over time, Fleet Marston found itself at the intersection of several routes that took travelers into the countryside and major towns.

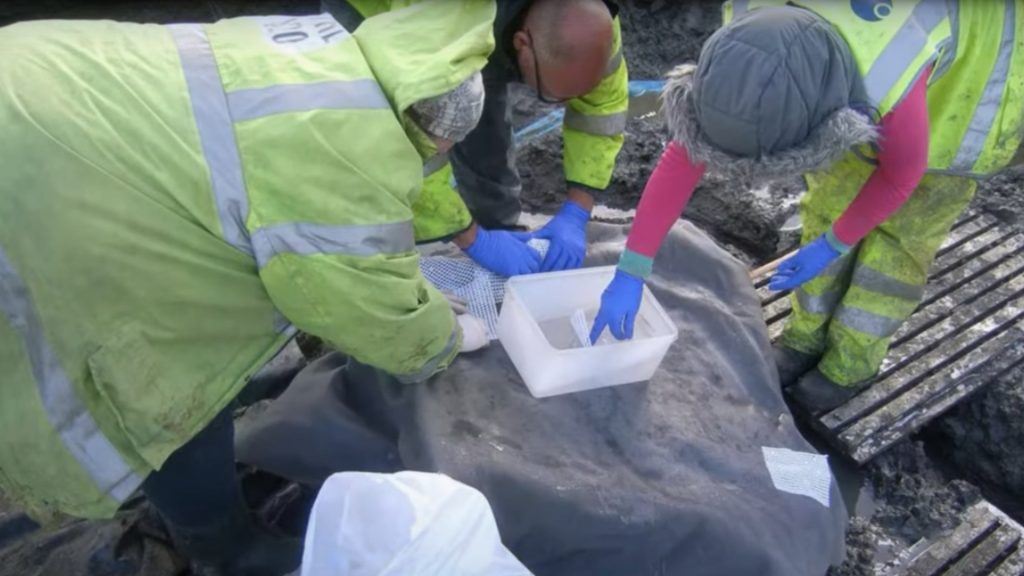

“Of particular interest were the eggs, which were a rare and exciting find. Despite the incredibly fragile nature of the eggs, the team on site were able to retrieve one intact,” a blog post from Buckinghamshire Council’s Heritage and Archaeology Team reads.

Cracked Shells: Fragile Eggs Meet Unfortunate Fate

Even though experts tried to remove them carefully, three eggs broke, releasing a strong sulfurous smell, but one remained intact. Oxford Archaeology experts believe that the waterlogged pit might have served as a type of Roman wishing well.

Edward Biddulph, the senior project manager at Oxford Archaeology oversaw the excavation. He expressed astonishment at finding what is believed to be the only intact egg from that period in Britain. He mentioned, “We usually find shell fragments, not complete eggs.”

Preserved For Centuries

He said: “The egg turned out to be even more amazing. It still contained its liquid, the yolk, and the white.” The yolk and albumen appear to have become mixed together. “We might have expected it to have leached out over the centuries but it is still there. It may be the oldest egg of its type in the world.”

Biddulph explained that the egg had been intentionally placed in a pit previously used for malting and brewing purposes. “This was a wet area next to a Roman road. It may have been the eggs were placed there as a votive offering. The basket we found may have contained bread.”

New Home For The Aylesbury Egg

The egg has been transported to the Natural History Museum in London. Biddulph admitted feeling a bit nervous riding the tube and walking around the capital while responsible for such an extraordinary and delicate artifact.

Carrying it in a special box on public transport in London for examination left Goodburn-Brown feeling particularly nervous, he added. However, the egg has mostly remained safe in their offices.

Ancient Egg Study At NHM

“Going forward, it will be very exciting to see if we can use any of the modern imaging and analysis techniques available here at the NHM to shed further light on exactly which species laid the eggs and its potential archaeological significance,” Russell said.

It has also been brought to London’s Natural History Museum. Douglas Russell, the senior curator of the museum’s bird eggs and nests collection was asked for advice on how to protect the egg and take out what’s inside.

Unlocking The Secrets Of The Aylesbury Egg

While there are older eggs with contents, like mummified ones, Russell explained that this egg is thought to be the oldest unintentionally preserved. A small hole might be made in the egg to extract its contents and learn more about the bird that laid it.

The egg is now kept at Discover Bucks Museum in Aylesbury while experts work on figuring out how to get what’s inside without breaking the fragile shell. “There is huge potential for further scientific research and this is the next stage in the life of this remarkable egg,” Mr Biddulph said.

Berryfields: From Agriculture To Urban Development

From the 4th Century, the Berryfields site had been converted to agricultural land according to the team from Oxford Archaeology. The Berryfields area where the dig took place is a major development area to the northwest of Aylesbury and is one of two major housing schemes in the town.

The two developments will lead to the creation of 5,000 new homes by 2021. The findings have been published in a new book called Berryfields.

Iron Age Workshop Unearthed Near Wittenham Clumps

Meanwhile. Earlier this month archaeologists uncovered rare evidence of an Iron Age blacksmith’s workshop that was in use around 2,700 years ago. The remains were unearthed by a team from DigVentures, a social enterprise organizing crowdfunded archaeological excavation experiences, downslope from the Wittenham Clumps.

The Wittenham Clumps are a pair of wooded chalk hills in Oxfordshire, England that are iconic landmarks in the area. The ancient workshop dates back to the earliest days of ironworking in Britain, according to researchers.

Master Craftsman Workshop Found

Excavations at the site have revealed a workshop containing artifacts such as pieces of hearth lining, hammerscale (a byproduct of the iron forging process), iron bar, and the exceptionally rare discovery of an intact tuyere. A tuyere is a nozzle through which air is forced into a smelter, furnace, or forge.

The evidence at the site, including the large size of the hearth, suggests that this was no ordinary village workshop. Instead, the archaeologists believe that it belonged to an “elite” or “master” ironworker who produced swords, tools, wheels, and other high-value objects.