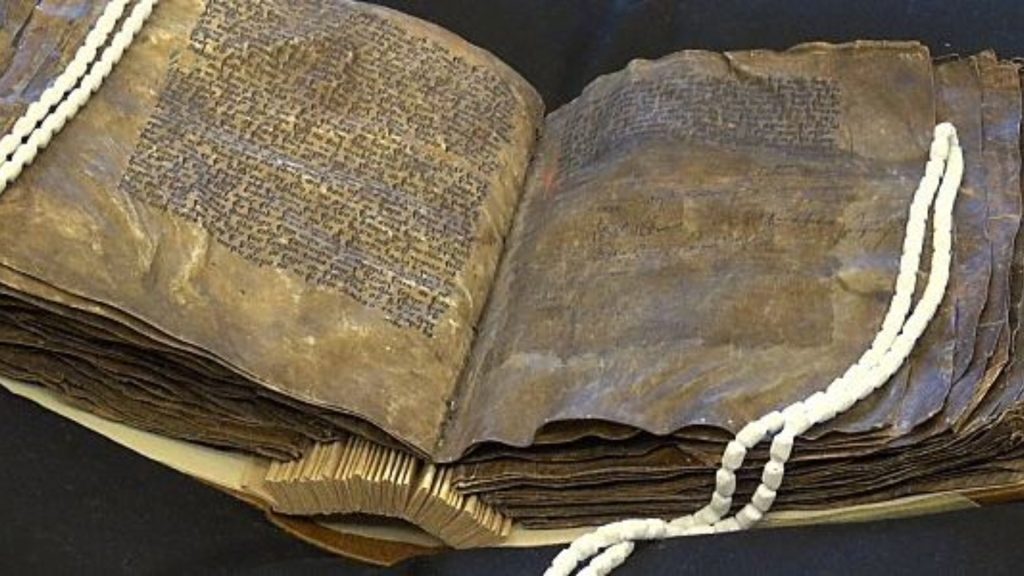

Written around the tenth century, the Icelandic Sagas are a collection of Viking stories, based on oral traditions, that follow the exploits of heroic warriors, explorers, and kings. For Icelanders, the sagas are a history book, but other researchers and historians often dismiss the sagas as fiction. When the ruins of a Viking village were found in Canada in the 1960s, just as the sagas detailed, it forced people to take a different view of the tales.

An intriguing theory emerged suggesting that some Vikings sailed much further south, arrived at Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, and interacted with the ancient Mayan people living there. Pulling information from both the Icelandic Sagas and the Mayan stories, a mind-blowing possibility is revealed. Could the Vikings have made it to pre-Columbian Mesoamerica?

Accomplished Sailors, Navigators, and Shipbuilders

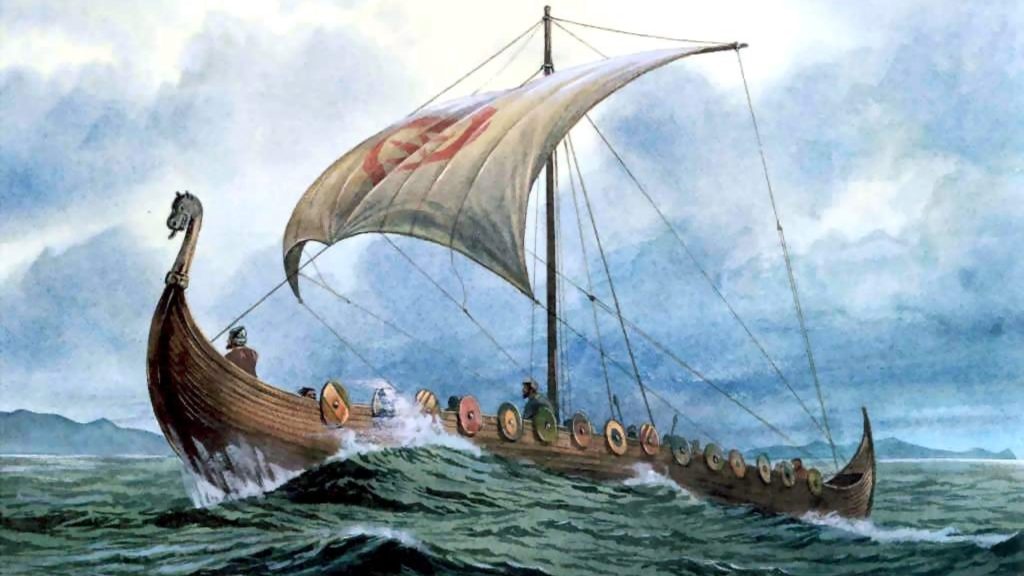

The distance between Iceland and the Yucatan Peninsula is vast. If anyone could have made such an ocean journey, it would have been the Vikings. Viking longboats were well-built, sea-worthy vessels that allowed the Vikings to conquer England and settle Iceland.

The Vikings sailed along the coast of Europe, into the Mediterranean Sea, and as far as Africa. From their settlements in Iceland, they built villages on Greenland and Canada. According to the Icelandic Sagas, Eric the Red’s ship encountered a storm that blew him off course. He landed in an area filled with grapevines he called “Vinland.” Many people believe he landed in what is now Martha’s Vineyard.

The Story of Bjorn Breithvikingakappi

In the same Icelandic Saga that describes Eric the Red’s discovery of Vinland, there is another story of a wayward Viking explorer that, according to some researchers, suggests the Vikings reached what is now Mexico. It is the story of Bjorn Breithvikingakappi.

Heartbroken to be on the losing end of a love triangle, Bjorn got in his longboat and stormed out of Iceland, headed for lands unknown. The sagas tell us his voyage took place in the year 998 and that Bjorn never returned to Iceland.

A Chance Encounter

The sagas continue to tell us that, more than three decades after Bjorn left Iceland, another group of Norse explorers, led by a man named Gudleif, was blown off course as they sailed around Ireland. After many days, they arrived in an unfamiliar place. It was the year 1030.

Gudleif and his men were immediately captured by the indigenous people and brought before their leader for execution. To their surprise and relief, the leader was a white man with a red beard who spoke to them in Norse. The bearded leader freed them and allowed them to sail away. Gudleif and his crew returned with the story of how they encountered the missing Bjorn.

The Legend of Quetzalcoatl

Quetzalcoatl was an important god to several Mesoamerican cultures, including the Toltec, Aztec, and Mayas. The name “Quetzalcoatl” translated to “feathered serpent” and, indeed, this deity is often depicted as a snake with feathers. But Quetzalcoatl also had the ability to take the form of a white-skinned human.

According to legends, Quetzalcoatl traveled in a serpent-esque vessel. Coincidentally, Viking longboats were built with figureheads fashioned to look like dragons. It is easy to see how a longboat with a dragon’s head might appear like a serpent.

Quetzalcoatl’s City

The Mayan tales explain that after Quetzalcoatl arrived, he built a city called Tula, which is an important archeological site today. The name of this city offers another clue to support the idea that the Vikings arrived in Mexico. During the time of Bjorn’s voyage, the term “Thule” or “Tule” was commonly used to refer to Scandinavia.

In ancient Greek and Roman times, “Thule” was assigned to the far northern regions of Europe. Bjorn would have known that Scandinavia was called “Thule,” but he would have also known that the real definition of this word was “a distant place beyond the borders of the known world.”

Quetzalcoatl Implemented Key Changes in Mesoamerica

If we accept the theory that Bjorn made it to Mexico and was revered as Quetzalcoatl, then it casts a new light on the teachings that this serpent god brought to the Mayans. One of these teachings was metallurgy. Indeed, at this time, the indigenous people of Mesoamerica learned how to make metal.

Another of Quetzalcoatl’s more significant changes was the banning of human sacrifices. The Mayans and Aztecs had long engaged in human sacrifices as a way to please their gods, but all this changed after Quetzalcoatl’s arrival in 998.

Viking-esque Beliefs in Mesoamerica

Thanks to the teachings of Quetzalcoatl – perhaps the Viking Bjorn – the Mayan people adopted the notion that warriors killed in battle automatically journey to the afterlife to reside with the gods.

Another of Quetzalcoatl’s new teachings evolved after he stated that he wanted his body to be burned on a funeral pyre upon his death. Some researchers theorize that this is when the Mayans began to cremate their dead.

The Timing Is Right

The Mayans developed an extremely accurate calendar system based on the positioning of the sun and moon. Each calendar cycle was 52 years. Ten cycles, therefore, was 520 years. The end of a ten-cycle period coincided with the return of Quetzalcoatl. If we accept that Bjorn’s arrival in 998 aligned with the arrival of Quetzalcoatl, then we can assume that this god would return 520 years later.

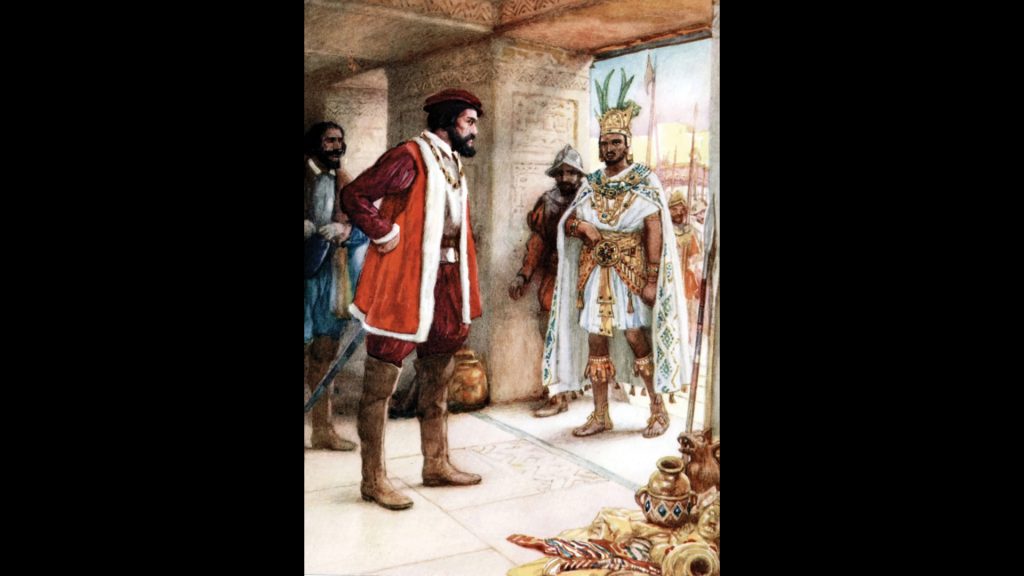

Exactly 520 years after Bjorn’s alleged arrival in Mexico would be the year 1518. This was the year in which Spanish conquistador Hernando Cortez landed in Mexico. The historical record tells us that the indigenous people welcomed Cortez with open arms. Things didn’t go bad for the indigenous people until later when Cortez conquered Mexico. Could it be that the Mayans thought Cortez was the returning Quetzalcoatl?

A Peculiar Mural at Chichen Itza

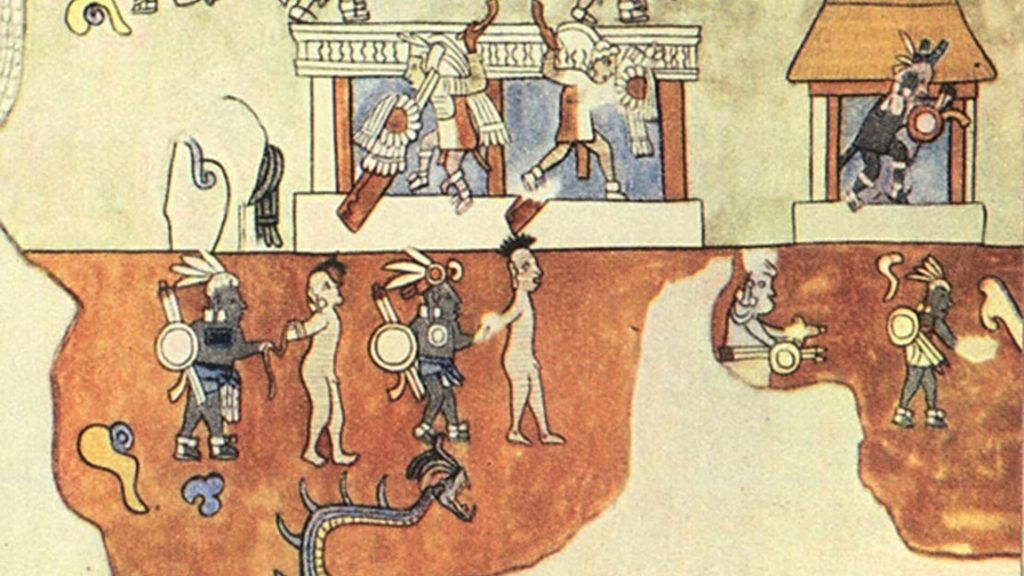

In the ancient Mayan city of Chichen Itza in the Yucatan, there is a painted mural that dates to around the year 900 AD. The mural shows white people with their hands tied behind their backs being led by brown people. Presumably, it shows that the Mayans had, at some point, captured white men.

Does the mural at Chichen Itza support the story in the Icelandic Sagas that a Viking named Gudleif and his crew were taken captive by the Mayans only to be released by their leader, they white-skinned, red-bearded Quetzalcoatl who was, in fact, another Viking named Bjorn? It is an intriguing possibility.