Insect eggs are smaller and much more delicate than bird or reptile eggs. Finding fossilized insect eggs is quite rare. That’s what makes a recent discovery in Oregon so remarkable. What is even more remarkable, however, is that researchers estimate that these insect eggs are about 29 million years old!

The fossil find, which is most likely the eggs of a grasshopper, not only dates back to the Oligocene Epoch, but is the only fossilized grasshopper egg pod yet to be unearthed by paleontologists.

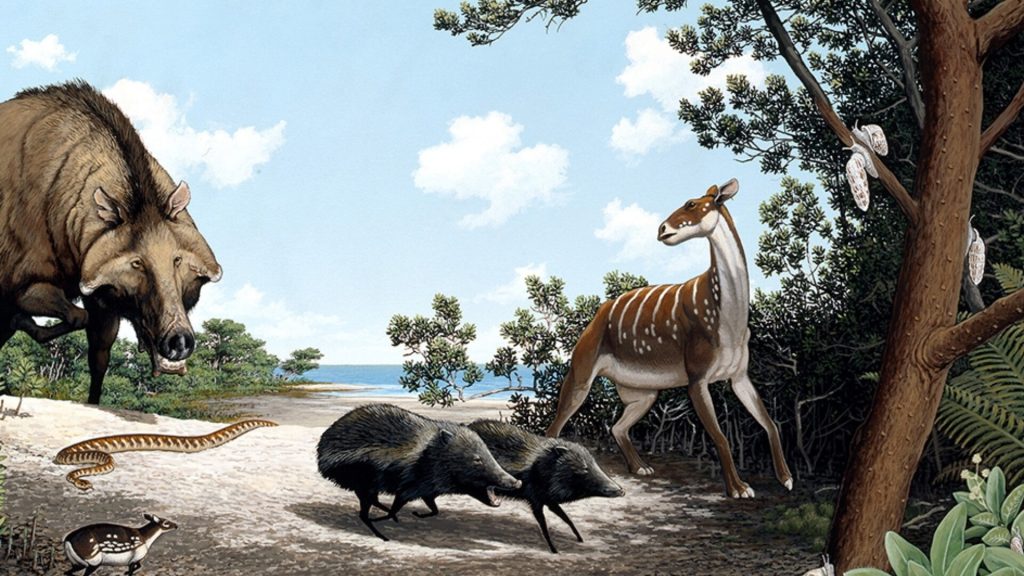

Planet Earth, Circa 29 Million Years Ago

The Oligocene Epoch was part of the Cenozioc Era of prehistory and took place from about 33.9 to 23 million years ago. This was a pivotal time for the young planet. The climate, once hot and humid, was beginning to cool. This is the time with ice caps formed in the polar regions.

Mammals were changing and evolving during this time as animal species became more diverse. The Oligocene Epoch saw the creation of horses and elephants, for example. Both insect life and marine life flourished as well, adapting to changing climate trends.

Oregon During the Oligocene Epoch

The area that is now Oregon experienced notable climate and geological changes during the Oligocene Epoch. Temperatures were cooling, shifting Oregon away from the tropical-like climate to a more temperate one. The weather patterns greatly impacted the evolution and adaptation of plants, animals, and insects living in the area.

Tectonic activity, as well as geological processes, rearranged the landscape of Oregon, which set the stage for the emergence of diverse life. Mammal family trees split to allow new species to evolve. The same was true for plants and insects.

A Day in the Life of a Grasshopper

During those times when Oregon was experiencing shifting temperatures, a female insect, believed to be a grasshopper, did what insects have been doing for millions of years. She burrowed into a sandy riverbank and deposited her eggs in an oblong egg pod.

The eggs – nearly fifty in total – were safely encased in their pod when the mother grasshopper filled in the burrow and hopped away. Her eggs were on their own now. If conditions were right, they should hatch in three to four weeks. The conditions, however, were not right.

Becoming Fossilized

The conditions may not have been conducive for the eggs in the pod to hatch, but they were ideal for the fossilization process. The first step to becoming a fossil is for the organic object – a living or once-living organism – to be quickly buried so that it is protected from other animals who would prey upon it.

Surrounded by sand and sediment, the egg pod lacked the oxygen it needed for the eggs to be viable. The sand allowed minerals to leach into the pod, replacing the organic tissue. The egg pod mineralizes or crystalizes, hardening into rock. In the case of this fossil, it remains in its safe burrow for years … 29 million years, to be exact.

An Unusual Discovery

According to Dr. Nick Famoso, manager and curator of the paleontology program at John Day Fossil Beds National Monument in Mitchell, Oregon, finding such a rare and delicate fossil near a creek bed was a surprise. Generally, these are not ideal conditions for fossilization to occur.

Dr. Famoso explained that these areas tend to be higher in bacteria that can destroy insect eggs before they have a chance to fossilize. They are used to seeing delicate fossil finds beneath lakes and rivers where the oxygen levels are low. He theorizes that the creek once covered the site, adding a layer of protection.

The John Day Fossil Beds National Monument

Found in eastern Oregon, the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument is located in a spot that is rich in geological and paleontological finds, including fossils. Fossil discoveries in the park range from large mammals, including prehistoric horses and camels, to plants, fish, and insects that span millions of years.

To preserve and protect the site, the National Parks Department acquired it and established it as the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument in 1975. Excavation work at the site has been ongoing, with fossil discoveries offering paleontologists a glimpse into ancient ecosystems that existed during the Eocene, Oligocene, and Miocene epochs.

An Easy and Unexpected Discovery

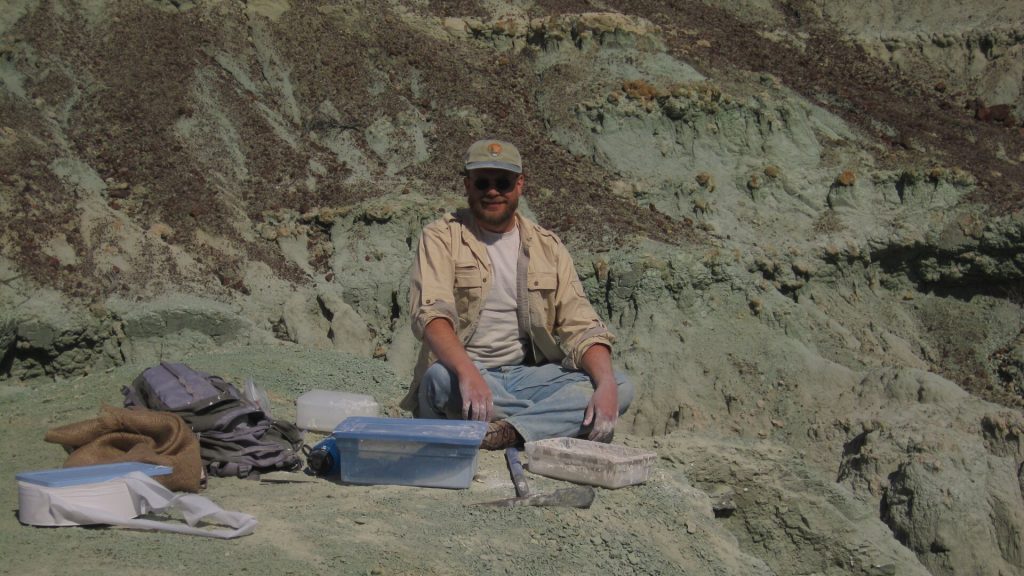

Christopher Schierup, a collection manager for the National Park Service, is the person who found the fossil. But he wasn’t fossil hunting at the time. He was doing a routine check of the excavation sites when something caught his eye.

The strange looking find, which Schierup immediately recognized as a fossil, was protruding from a rock that had recently rolled down an incline. As Dr. Famoso explained, “It didn’t require any tool work to get it out of the ground.” Schierup brought the find to the park’s lab.

Identifying the Fossil

When they first saw the fossil, some of the researchers at the John Day Fossil Beds believed it to be a cluster of ant eggs. As Dr. Famoso explained, the curvature of the pod made him skeptical. So he called in an expert … Jaemin Lee, a doctoral student studying at the University of California, Berkeley in the field of evolutionary ecology.

Lee agreed with Famoso that the fossil was not ant eggs. The next stop for Dr. Famoso was to take the fossil somewhere where it could be analyzed by imaging devices.

CT-Scans Told More of the Story

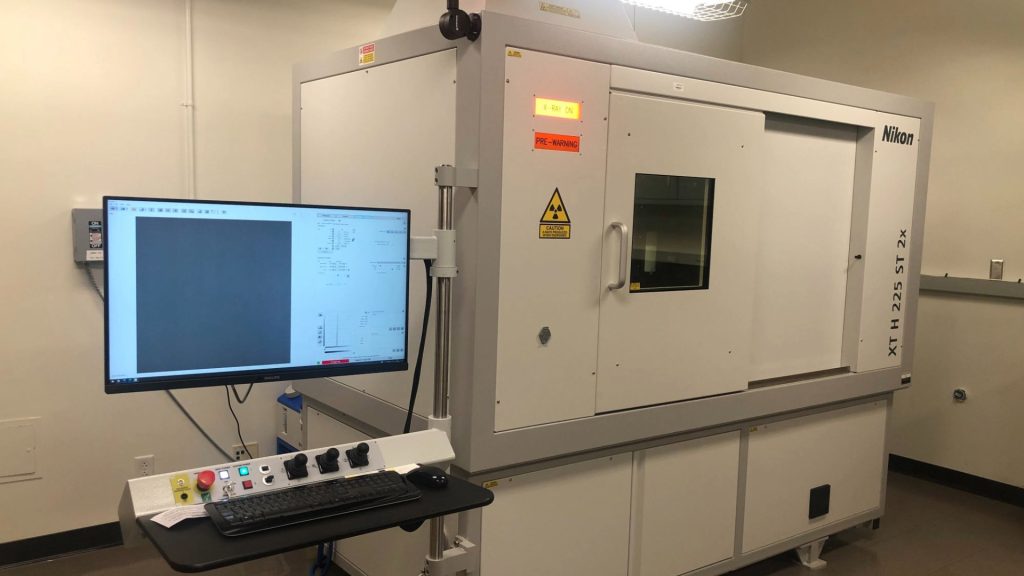

Dr. Famoso contracted Angela Lin, the director of X-Ray Imaging Research at the University of Oregon’s Knight Campus, located in Eugene, Oregon. Lin put the fossil under a micro-CT scan.

“Just being able to see that internal structure and really properly describe what these things look like – that was something that was really exciting for us,” said Dr. Famoso said. The micro-CT scan revealed something amazing.

Not an Egg Cluster, But an Egg Pod

Dr. Famoso explained, “We discovered that there was this protein layer that was holding everything together.” That protein layer was the calling card of an ootheca, a type of subterranean egg pod.

According to Lee, “Belowground egg pods are currently produced only by two groups of insects.” Those groups are heelwalkers of the order Mantophasmatodea and grasshoppers, members of the suborder Caelifera of the order Orthoptera.

A Prehistoric Discovery

Additional micro-CT scans and further testing has shown that the fossilized grasshopper egg pod is millions of years old. The findings show that the grasshopper likely laid eggs 29 million years ago. Still, the construction of the pod and the eggs themselves are a close match to those of modern grasshoppers.

Dr. Famoso noted that discovery offers clues about the evolution of grasshoppers, as well as the ancient ecosystem of Oregon during the Oligocene Epoch. It also shows that prehistoric grasshoppers were, like some of their modern relatives, burying their egg pods underground.

The Only Fossilized Grasshopper Egg Pod

Since insect eggs are so fragile and rarely withstand the fossilization process, this discovery is quite exciting for paleontologists and evolutionary scientists like Lee. It provides clues to insect reproduction millions of years ago and how it has evolved over time.

Lee explained, “This work is exciting because such exceptional preservation provides unique insights to one of the least understood life stages of insects, particularly in the geologic past.”

What Does a Fossilized Egg Pod Look Like?

A cursory look at the grasshopper egg pod revealed 28 visible eggs. Each oval egg measures 0.18 inches long and 0.07 inches wide. Although tiny, Dr. Famoso explained that they are approximately the same size and shape as modern grasshopper eggs.

The micro-CT scan showed that there are at least two dozen additional eggs deeper within the pod. The eggs are arranged in a radial pattern with four to five layers. Dr. Famoso added that many of the eggs were hollow. Others, he said, had been filled with sediment. “The mineralization that we were able to see in each of the eggs made it very clear that that was a fossilization structure,” he said.

The Global Insect Egg Database

The task of comparing the 29-million-year-old grasshopper eggs with other specimens was impossible. There are so few fossilized insect eggs that have been discovered … and none of them have been grasshopper eggs.

Lee turned to a global insect egg database, which contains specimens from more than 6,700 living insects, when trying to identify the eggs. In doing so, Lee determined that the eggs came from a previously unknown grasshopper species.

An Unknown Grasshopper

As Lee explained, “I compared the defining egg features, including size, length to width ratio, and curvature of the individual eggs to those of the living ones. Such large, elliptically curved eggs in a large clutch size are unknown from any other living groups of insects other than grasshoppers and locusts.”

It is rather unusual to identify a previously unknown species of insect from its fossilized eggs, but as Dr. Famoso explained, “There just isn’t anything else like this in the fossil record anywhere that we know of.”

A New Area of Study

Oxford University paleo biologist Dr. Ricardo Perez-de la Fuente, was not directly involved in the research of this fossil but he recognized the bigger picture that this find represents.

Not only is it, as Perez-de la Fuente noted, “the first to be recognized as belonging to orthopterans – grasshoppers and their kin – in the fossil record,” but it adds a new area of study.

“Formalizing the Description of Immature Stages of Insects“

The branch of science dealing with the classification of eggs is called as ootaxonomy. Studying eggs “can provide paramount data on the evolution, behavior and ecology of insects in deep time, but which tend to be neglected in paleontological studies,”

Perez-de la Fuente explained. The discovery of this fossil “represents an important step towards formalizing the description of immature stages of insects,” he added. Further study on prehistoric fossilized insect eggs, however rare, can provide valuable insight into how insect reproduction has evolved and the factors that contribute to these changes.