Documentary film crews, like journalists, are supposed to report on stories, but occasionally, something unexpected happens that forces them to become part of the story. That’s what happened to two people this summer who made an accidental and historic discovery in the Great Lakes.

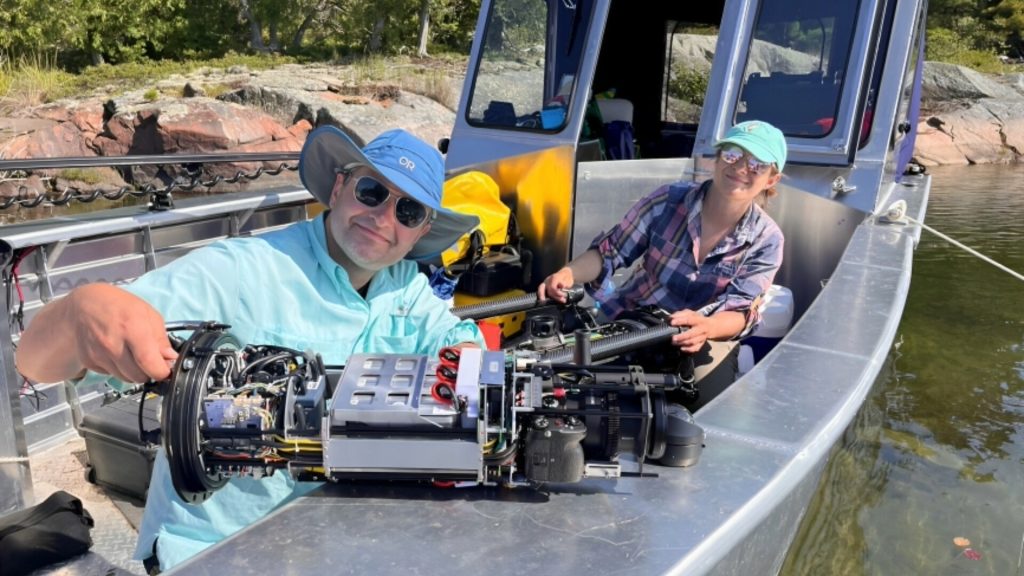

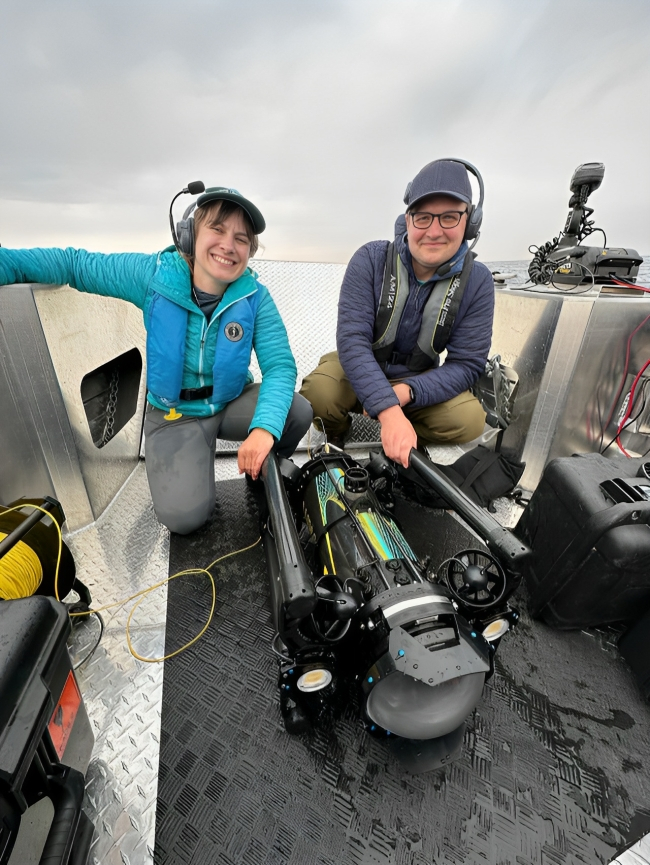

Filmmakers Yvonne Drebert and Zach Melnick were not shooting footage for a documentary on Great Lakes history. Instead, their work is more environmental in nature. But as we will see, these two issues are more interconnected than we might think.

All Too Clear

Yvonne Drebert and Zach Melnick’s forthcoming work, a film titled “All To Clear,” documents the non-native quagga mussels that have invaded the Great Lakes and are threatening the ecosystem. These freshwater mollusks are native to Eastern Europe and likely hitchhiked their way into the Great Lakes in ballast water of transoceanic ships.

These mussels are a threat because they reproduce rapidly and filter large amounts of plankton from the water, disrupting the food chain. Their massive colonies can damage underwater infrastructure and alter the chemistry of the water. Drebert and Melnick hope to show the significant ecological and economic impacts of the invasive quagga mussels in “All Too Clear”.

Lake Huron’s Unique Geological History

Lake Huron, one of the five Great Lakes, boasts a fascinating geological history that contributes to its unique characteristics. Formed around 10,000 years ago during the last Ice Age, Lake Huron’s basin was carved by the powerful forces of glaciation. As massive ice sheets receded, they left behind a vast depression that gradually filled with water from the melting glaciers and runoff, forming the expansive lake we see today.

What sets Lake Huron apart is its diverse and captivating shoreline, featuring picturesque landscapes, rugged coastlines, and more than 30,000 islands, including the famous Manitoulin Island, which is the largest freshwater island in the world. The lake’s distinctiveness also lies in its interconnectedness with Lake Michigan through the Straits of Mackinac, creating a dynamic water system that supports rich biodiversity.

A Vital Shipping Lane

Lake Huron has played a pivotal role in the maritime history of North America, serving as a crucial waterway for shipping and trade. The lake’s strategic location within the Great Lakes system made it an integral part of a vast transportation network connecting the interior of the continent to the Atlantic Ocean. With the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, Lake Huron became a key link in the chain that facilitated the movement of goods, fostering economic growth and development in the region.

As industries expanded, steamships replaced traditional sailing vessels, further enhancing the efficiency of transportation on the lake. The construction of canals and locks, such as the Soo Locks at Sault Ste. Marie, allowed ships to navigate the elevation changes between Lake Huron and Lake Superior. Over the years, Lake Huron has witnessed the evolution of shipping technologies and the rise of commercial fleets carrying goods ranging from timber and minerals to manufactured products.

A Fragile Ecosystem

Invasive species collectively require ongoing management strategies to mitigate their impacts on the fragile Great Lakes ecosystem. The Great Lakes have been significantly impacted by the introduction of invasive species, causing ecological disruptions and posing threats to native biodiversity. One of the most notorious invaders is the zebra mussel, a close relative of the quagga mussels, which arrived in the 1980s, likely transported in ballast water from transoceanic ships.

Another formidable invader is the Asian carp, particularly the silver and bighead carp, which pose a significant threat due to their voracious feeding habits and rapid reproduction, potentially outcompeting native fish populations. The invasive sea lamprey, introduced in the mid-20th century, has had devastating effects on native fish, leading to extensive control efforts.

About Those Colonies of Mussels

Individual quagga mussels look harmless enough … only about two centimeters long. But they cluster in large colonies and will completely cover submerged objects, disguising and camouflaging them. A female quagga mussel can lay as many as a million eggs in one season, so it is easy to see how populations can quickly explode.

The quagga mussels don’t just pose a threat to the native plants and fish of the Great Lakes. They also threaten to destroy historic shipwrecks. The animals cling to wooden shipwrecks and eat away at the hulls. They can even destroy metal objects by speeding up the decaying process.

A Surprise Discovery

Yvonne Drebert and Zach Melnick spent a lot of time on the waters of the Great Lakes over the summer, shooting footage for their film. In June, they were boating on Lake Huron with friends when they were told about a strange, mysterious mound deep beneath the waters.

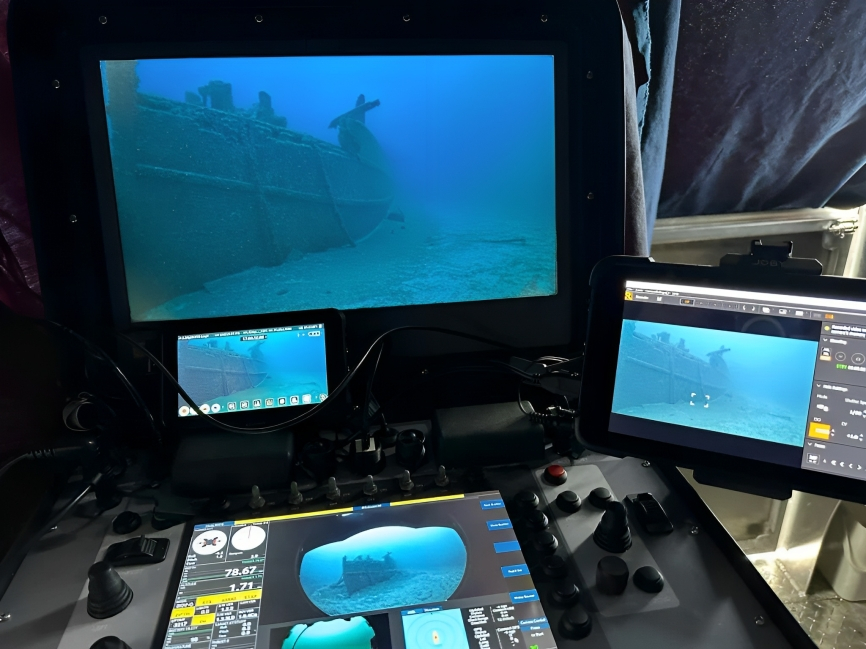

They steered their boat toward the west side of Ontario’s Saugeen Peninsula in Lake Huron. Once there, they deployed their remote operated underwater vessel which they used in their filmmaking. The vessel’s camera sent back video of an unknown object on the bottom of the lake, some 280 feet below the waves. But what were they looking at?

A Mussel-Encrusted Wreck

The strange underwater mound was completely covered in quagga mussels, a fact that didn’t surprise Drebert and Melnick as much as it saddened them. Upon further inspection, it became clear that the mound was, in fact, a shipwreck. An old one, at that!

Drebert and Melnick were unable to read the name of the vessel because the quagga mussels obscured the ship’s hull. Following protocol outlined in the Ontario Heritage Act, they reached out to Great Lakes maritime historians to report the wreck. They were put in contact with marine archaeologist Scarlett Janusas and Great Lakes maritime historian Patrick Folkes. They secured a permit from Ontario to investigate the wreck more thoroughly.

Looking for Underwater Clues

Subsequent dives at the site gave the crew the opportunity to take measurements and look for clues that could help identify the ship. They determined that the vessel was 148 feet long, 26 feet wide, and a little over 12 feet tall. These were important clues, but what they found next was just as helpful in identifying the vessel.

Scatters on the lake floor around the wreck, Drebert, Melnick, and the others found coal. Great Lakes shipping vessels transported a number of goods, including timber, iron ore, and grain. Knowing what the ship was carrying when it went down would narrow the list of known ships that were lost in the lake.

Putting a Name to the Wreckage

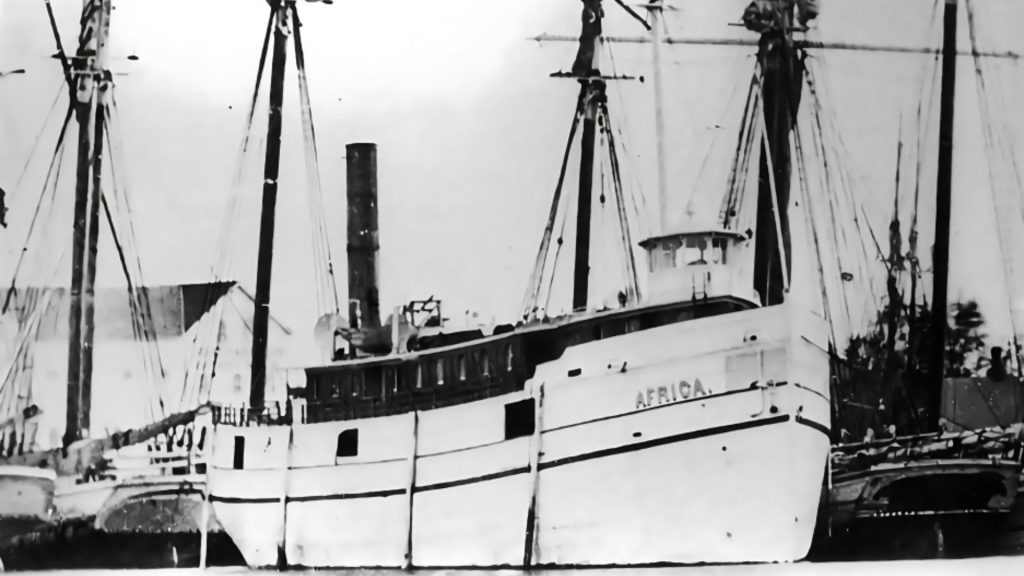

Based on the measurements of the wreckage and the coal that was found, the clues pointed to one ship … a vessel that was exactly that size and was hauling a load of coal when it disappeared from history. The name of that ship was the Africa.

Until now, the final resting place of the Africa was unknown. Putting a name to the wreckage, however, helped the researchers reconstruct the final days of this ill-fated ship. When did the Africa go down? How did it sink? What happened to its crew?

The Story of the Africa

Drebert and Melnick learned that the Africa set sail on October 5, 1895, from a port in Ashtabula, Ohio. In addition to a load of 1,270 tons of coal, the cargo ship was towing a schooner, the Severn, behind it.

The Africa was heading toward Owen Sound, Ontario, to deliver its cargo of coal. It sailed through Lake Erie and up the St. Clair River before entering Lake Huron. But this is when things took a tragic turn for the Africa and its crew.

The Fierce Great Lakes

Because they are lakes, many people assume that the Great Lakes are calm and less dangerous than the open ocean, however the Great Lakes have a reputation for turning violent without warning. Shipping vessels on the Great Lakes are at the mercy of high winds and terrible snowstorms.

As marine historian Patrick Folkes explained, in the area around the Saugeen Peninsula alone, more than a hundred ships disappeared or crashed between 1848 and 1930, the timeframe when the Africa was lost. Only about half of those ships have been found and definitively identified. The greatest loss of ships in Lake Huron occurred in a single storm less than 20 years after the Africa sank in an event known as the Great White Hurricane.

Lake Huron’s Great White Hurricane of 1913

Eighteen years after the loss of the Africa, Lake Huron was the scene of the deadliest and most destructive natural disaster to befall the Great Lakes. From November 7 to 10, 1913, two storm systems merged to form a perfect storm – a blizzard and a hurricane.

Dubbed the Great White Hurricane, this storm had sustained hurricane force winds with blizzard conditions. The snow was so thick and heavy that the light from lighthouses couldn’t penetrate through it. In all 19 ships sank in this storm. An additional 19 ships were damaged or ran aground. The total loss of life exceeded 250 people.

The Africa Versus a Great Lakes Storm

Although the Africa was lost 18 years before the Great White Hurricane, it was the same combination of driving snow and high winds that spelled doom for this ship. The storm hit as the Africa, with the Severn in tow, approached the Saugeen Peninsula.

As the waves rocked both ships and the crew were blinded by the snow, the captain of the Africa made the decision to cut the tow line and release the Severn. That act saved the men aboard the Severn. It became grounded on a rocky reef. The next morning, the crew of the Severn was rescued by a passing ship.

The Fate of the Africa

The crew of the Severn survived the storm, but the Africa wasn’t so lucky. After the captain untethered the Severn, the men aboard the schooner watched as the Africa disappeared into the night, never to be seen again.

When the Africa failed to arrive at its destination in Owen Sound, it was assumed that the Africa sank in the storm. There were 11 men aboard the ship and all of them perished in the tragedy. In the weeks following the storm, the bodies of five of the Africa’s crew members washed ashore. The others may still be in the wreckage.

Preserving Great Lakes Shipwrecks

The Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum, located at Whitefish Point on Lake Superior, commemorates the maritime history and the perils faced by sailors navigating the treacherous waters of the Great Lakes. The museum, housed in the historic 1861 Whitefish Point Light Station, is dedicated to preserving the rich maritime heritage of the region, with a particular focus on shipwrecks.

The museum actively participates in the preservation of shipwrecks through collaborative efforts with maritime archaeologists and historical preservationists. By documenting and researching these underwater time capsules, the museum contributes valuable insights into the challenges faced by mariners throughout history.

The Quagga Mussels Helped Find the Africa

The crew of the Severn had a general idea of the location of the Africa, however the shipwreck stayed hidden for 128 years before it was discovered by Drebert and Melnick. It can be argued that, if it wasn’t for the invasive mollusks, the Africa would not have been found.

First, it was the quagga mussels that brought Drebert and Melnick to Lake Huron. Second, the mussels are known to filter the water surrounding them, removing plankton, dirt, and microplastics that make the water murky. Drebert and Melnick’s remote camera may not have been able to clearly see the wreckage had it not been for the quagga mussels.

A New Chapter in Their Documentary

As Zach Melnick explained, the initial focus of “All Too Clear” was on the incredible filtering abilities of the quagga mussels, which has caused the Great Lakes to be up to three times clearer than they previously were, the discovery of the Africa has added a new chapter to their documentary.

This new chapter will consider the impact the invasive mussels are having on the cultural heritage of the Great Lakes. Because of the destructive power of the quagga mussels, many older, wooden shipwrecks are being eaten away by the mollusks. Others, like the Africa, have become so encrusted with quagga mussels that it makes it harder for marine archaeologists to identify shipwrecks.

Shining the Spotlight on the Invasive Mussels

In creating their documentary, Melnick and Drebert want to shine a spotlight on the problem of invasive species in the Great Lakes. The quagga mussels have had a detrimental effect on fishing in the Great Lakes and have threatened the livelihood of commercial fishermen. Native plants and animals are also in danger because of the quagga mussels.

And then there is the problem of the potential loss of sunken ships like the Africa. Now that Melnick and Drebert have a fuller understanding of how the quagga mussels are impacting multiple areas, they can paint a better picture of the need to eradicate non-native species from the waters. Of course, their upcoming film, “All Too Clear,” will include footage from the Africa, as the ship and the filmmakers have now become part of the story.